McMullen Museum of Art

Permanent Collection

Studio of Chōkichi Suzuki (1848–1919)

Eagle, c. 1890s

Bronze, gold, shakudo

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College

Lower section of base donated by Peter Marino and Bryan Fleming

Victoria Weston

Professor of Asian Art History, UMass Boston

Given to Boston College by Larz and Isabel Anderson of Brookline in 1954, this magnificent bronze eagle initially was displayed outside Boston College’s Alumni Hall.

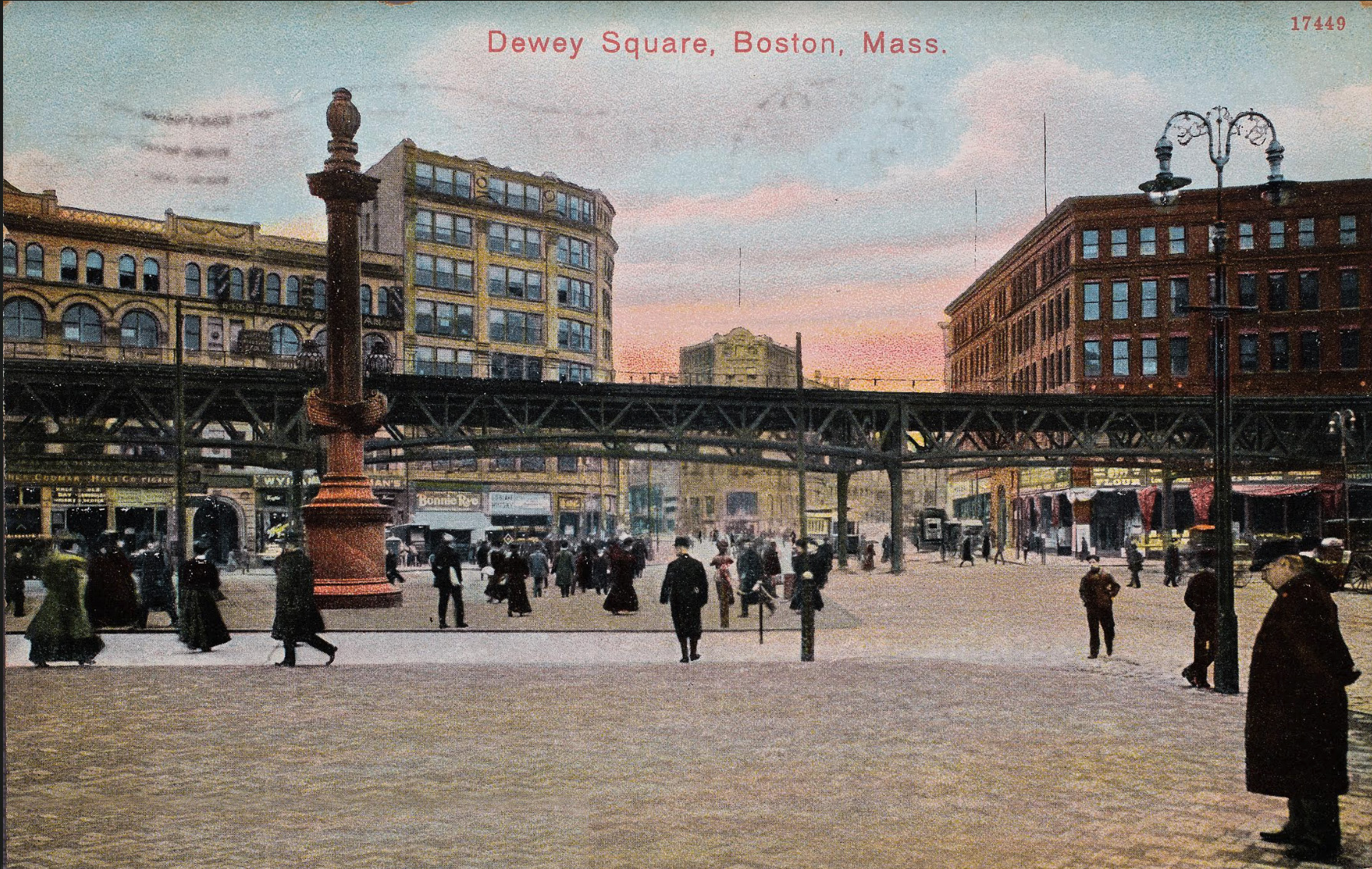

After Boston’s Central Artery project in the 1950s eliminated Dewey Square in front of South Station, Boston College acquired the 1899 monument commemorating Admiral George Dewey’s naval victories during the Spanish-American War that had stood there (see photo). Topped by a spherical lantern, the monument comprised a pink granite column with a stone sculpture of four addorsed ships’ prows tipped with eagle heads facing the four directions.

Boston College repurposed the monument by removing the sculpture and eliminating the lantern. The stone sculpture was first installed in the quadrangle in front of Lyons Hall. In 2018 it was moved outside the McMullen Museum, where it is now visible through the window behind the eagle.

The University gilded and mounted the bronze eagle on the pink granite column and placed it in front of Gasson Hall. In order to secure the eagle on top of the column, its separately cast rock-like base was removed and the join was trimmed to make it flat, unfortunately eliminating some decorative vines. The golden eagle remained atop its marble column until the 1990s by which time exposure to the elements had caused the sculpture to crack. In 1993 the damaged eagle was taken to Skylight Studios in Woburn, Massachusetts, where a replica was cast to replace the original on the column.

When viewing the replica with students from Showa Boston Institute in the 2010s, Rus Gant suspected the original sculpture was Japanese. He found the original at Skylight Studios and alerted the McMullen Museum of its whereabouts and condition. The Museum transferred the eagle to Boston College where experts in Japanese art confirmed the bronze to be a masterpiece of the Meiji period. The McMullen then engaged Rika Smith McNally & Associates to restore and repatinate the original in accordance with period colors. The conserved eagle formed the centerpiece of an exhibition, Eaglemania: Collecting Japanese Art in Gilded Age America, at the McMullen in 2019. The eagle’s removed lower base was presumed lost until, during the exhibition, a former Boston College contractor revealed that he had preserved it. The lower section of the base was reunited with the eagle in March 2024.

Suzuki Chōkichi

Suzuki Chōkichi was the most important caster of monumental bronzes during the Meiji period (1868–1912). His ability to render animals, particularly eagles and hawks with compelling naturalism set him above his peers. He led the metalworking department of the Pioneering Craft and Commerce Company (Kiryū Kōshō Kaisha) in the later 1870s and 1880s, which was formed to create major artworks for world’s fairs.

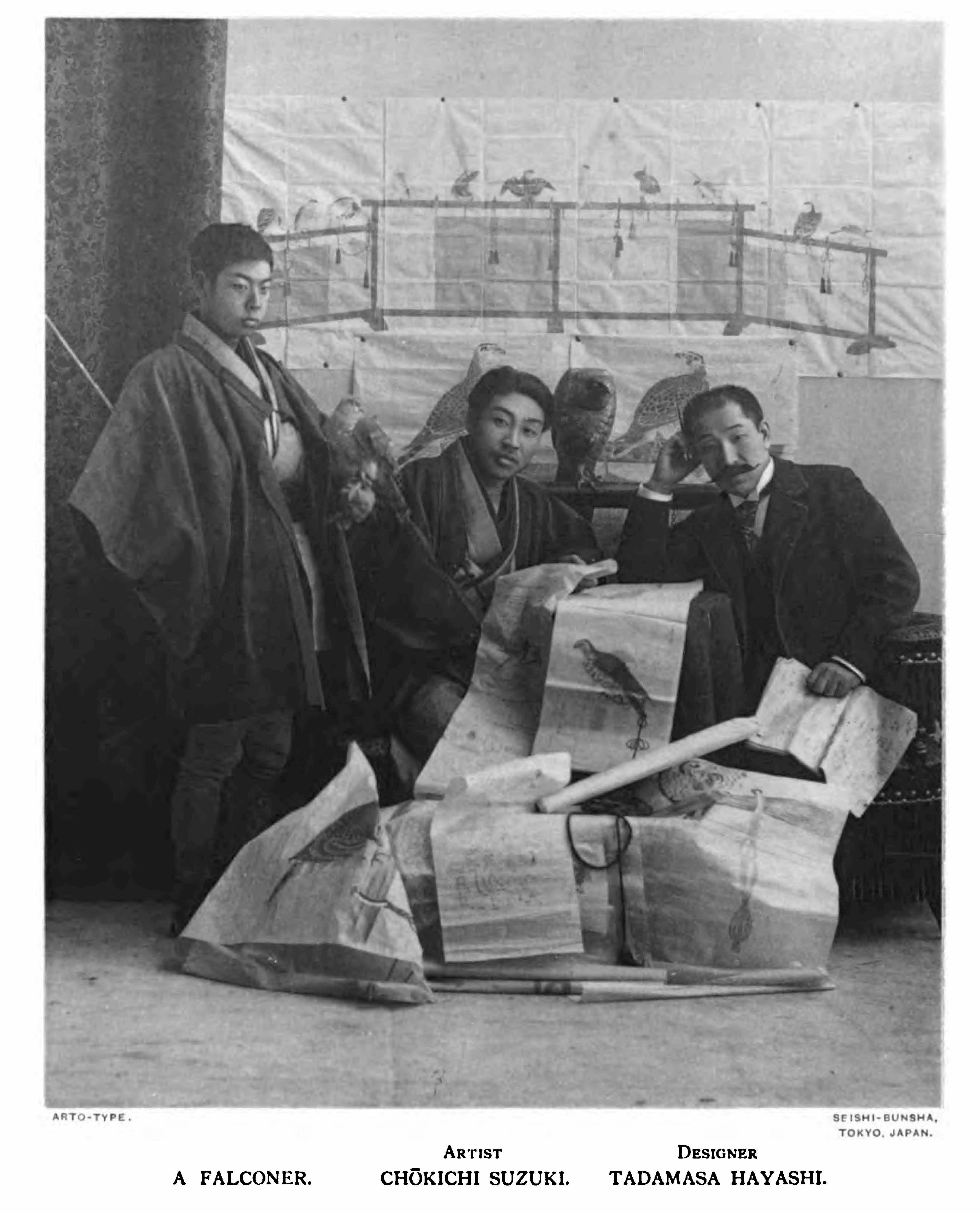

The photograph here shows Suzuki with a falconer and designer Tadamasa Hayashi. The Japanese government rewarded Suzuki for his service in 1891 by appointing him “Artist-Craftsman to the Imperial Household” (teishitsu gigeiin), a rank only one other metal artist held. In his later years, Suzuki ran his own company. Many of Suzuki’s works are unsigned. No signature has been found on the Boston College eagle, but comparison to a Suzuki-attributed eagle in the Metropolitan Museum of Art demonstrates clear kinship of style.

Few artists in Meiji-period Japan were equal to the task of casting a monumental and naturalistic eagle with subtle details like finely rendered eyes, individual feathers, and ornamental vines. The delicately incised lines surrounding the eye sockets on the Boston College eagle recall a painter’s use of ink outlines. The gold on the eyeballs with black pupils and the accentuated brows give the bird a dramatic, piercing gaze.

Installation in the Anderson Garden in Brookline

Larz and Isabel Anderson purchased the eagle in 1897 on their honeymoon in Japan. In 1907, the Andersons constructed one of America’s earliest Japanese gardens on their Brookline estate, Weld. The garden diverged from Japanese practice in only one important respect: the addition of garden statuary, including the eagle (see image). “Above you rises the huge bronze eagle,” wrote Isabel, “he is the one high point, the key of the Japanese garden.” The eagle with its bronze-cast pedestal of craggy rock did indeed rise above everything, even the clipped trees, because the Andersons elevated it further on a plinth set in a pond.

The Andersons also collected bonsai trees, many of which are preserved at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in Boston.

John McCoy

Assistant Director, McMullen Museum

Note on conservation

As described above, when Boston College’s eagle was placed atop the column near Gasson Hall in 1955, its lower section was detached and the upper section was cut to fit its new setting. After discovery and return of the missing base, the divided sculpture was sent to Bob Shure at Skylight Studios for re-attachment and for conservation by Rika McNally & Associates. A metal collar and internal armature were built to rejoin and support the eagle and base, as the pieces no longer fit together as designed.

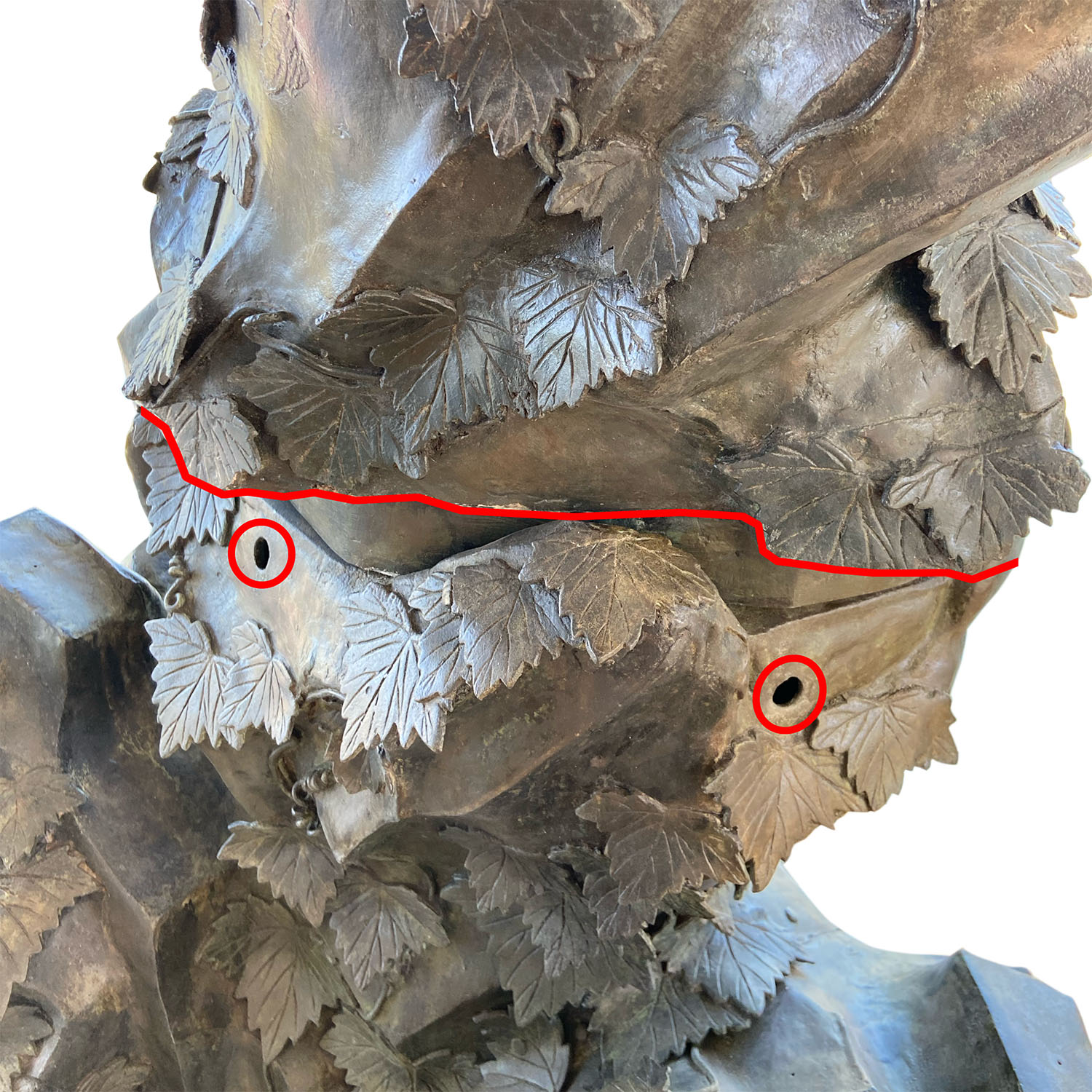

The current join between top and bottom of the sculpture, with the highlighting showing the cut edge and the holes that most likely were used to fasten the sections.

Examining the imperfect transition between upper and lower sections today, a viewer may imagine how the original join looked like. The first photo (above) shows the cut edge (the red line) where bronze was removed. On the base, one can observe holes (circled in red) where prongs from the missing section probably were inserted. The second photo (below) is a depiction of how additional bronze leaves might have hidden this connection.

Photographic reconstruction of how the join might have originally appeared. Passages of leaves conceal the seam as well as provide projections on their undersides to fit into the base holes.

Museums often display works that have been damaged, repaired, retouched, or otherwise altered from their original states, and conservators and curators must decide how best to deal with these features in a way that is attractive and transparent, while honoring the objects’ histories.

Diana Larsen

Assistant Director, McMullen Museum