McMullen Museum of Art

Permanent Collection

John La Farge (1835–1910)

St. John the Evangelist, Christ Preaching, St. Paul, 1889

Opalescent leaded glass

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Gift of William M. & Alison S. Vareika ’74, P’09, ’15, LP’16 in honor of William P. Leahy, SJ, J. Donald Monan, SJ, William B. Neenan, SJ, and John La Farge, SJ

Jeffery Howe

Professor Emeritus, Art History

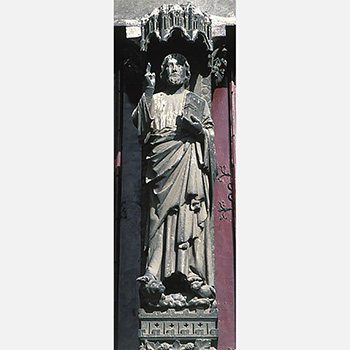

John La Farge, Christ in Majesty, detail, 1883. Trinity Church, Boston (photo: Jeffery Howe).

Beau Dieu, trumeau sculpture, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220.

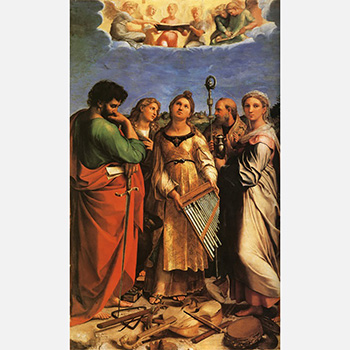

Raphael, The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia, 1516. Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna.

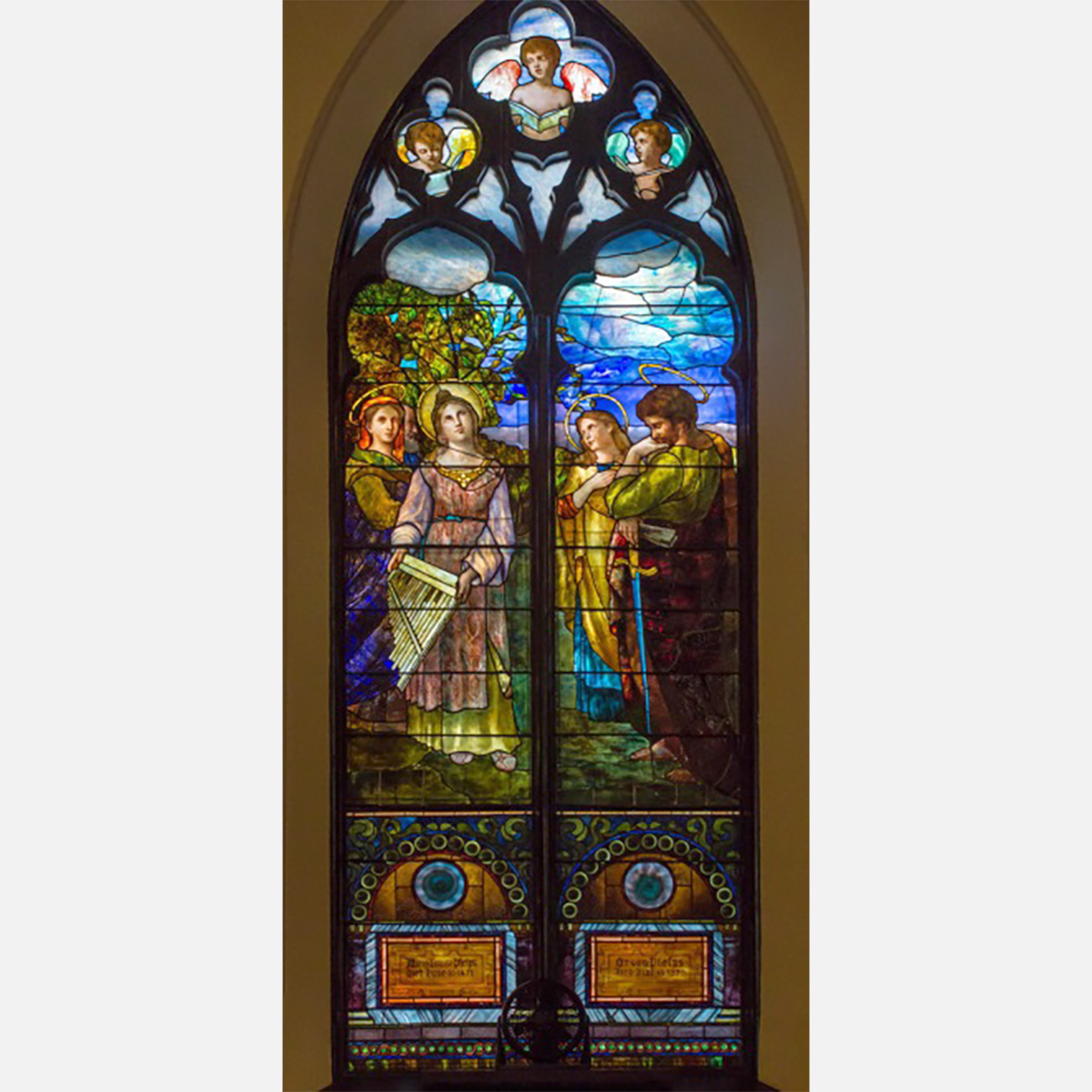

Louis Comfort Tiffany, St. Cecilia, 1887. Trinity Church, Buffalo (photo: Jeffery Howe).

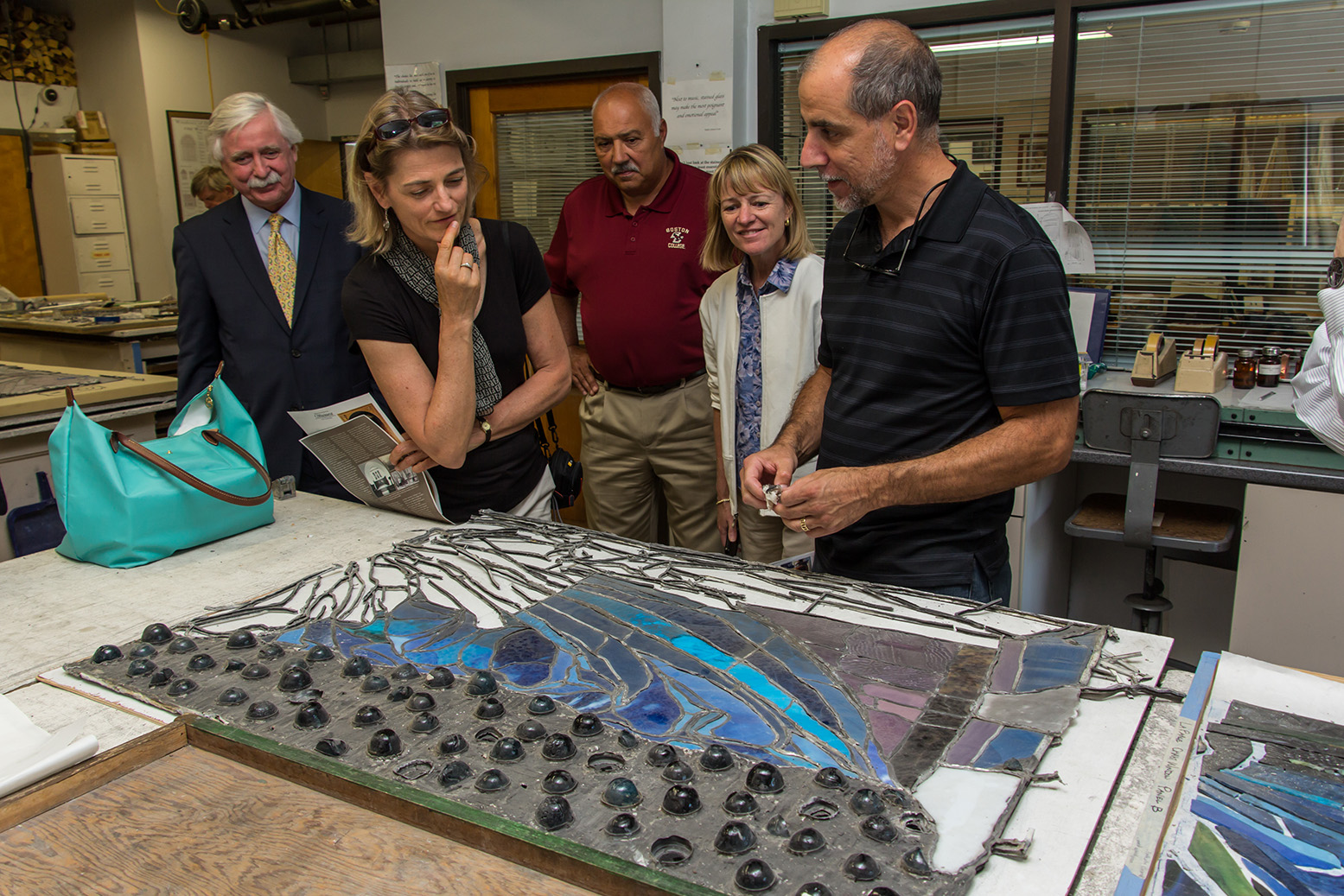

William Vareika, Diana Larsen, Stephen Connors, Mary Nardone, and Roberto Rosa at Serpentino Studios, June 2014. A portion of the figure of St. Paul is under restoration (photo: Jeffery Howe).

St. John the Evangelist at left was commissioned by Mary Elizabeth Meredith in memory of her parents, Walter Farnsworth and Elizabeth Loring Young. Here the top panel contains a phrase from the ancient hymn Te Deum laudamus (“Thee, O God, we praise”). Christ Preaching is dedicated to the Rev. Charles James Bowen, the church’s minister from 1865 until his death in 1870. The upper panel bears text from John 13:35. In contrast to the gentle image of John, St. Paul appears as a militant saint, bearing a sword with an inscription from Second Timothy 4:7, the preceding line of which reads: “I have fought a good fight.” The window memorializes Leonard Ware and his wife Sarah Ann Minns.

The figure of Christ is very similar to the window on the west façade of Trinity Church in Boston from 1883 (see photo). Unlike the figure in Trinity Church, however, this image of Christ has no halo, in consideration of the Unitarian clients who avoided such overt symbolism of divinity. Both figures are modeled on the statue of Christ known as the “Beau Dieu” (handsome God) at Amiens Cathedral in France (see image).

The model for St. John was Mary Whitney, John La Farge’s longtime mistress and one of his favorite models until 1892, when she left New York to care for her aged parents. Both the figures of St. John and St. Paul are based on those in Raphael’s painting of The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia of 1516 (see image). Raphael’s painting was copied in stained glass by Louis Comfort Tiffany in 1887 for a window in Trinity Church, Buffalo (see photo). La Farge was to create some of his finest windows for this church beginning in 1889, and it is not unlikely that Tiffany’s use of the Raphael image stimulated La Farge to borrow aspects of it himself for our windows. Tiffany reversed Raphael’s composition, suggesting that he was working from a print rather than a photograph of the painting. La Farge also uses this reversed orientation of St. Paul.

The conjunction of these three figures is not random; they are united in a timeless grouping known as a “sacred conversation,” based on precedents in Renaissance art. La Farge wrote: “Perhaps the most celebrated of the ideal arrangements that we know under the name of Sacred Conversations is Raphael’s Saint Cecilia. With the ‘Madonnas’ whom he has represented in the meaning of the Great Lady Patroness surrounded by a court of worshippers, or beings influenced by her, the Madonna and the Child are so immeasurably important that we do not at once classify these great paintings as belonging to the simpler idea of a meeting of people outside of Time.” La Farge sought to imaginatively enter into the past through the imitation of traditional art, a kind of spiritual act of devotional repetition.

Blue glass cabochons (a signature of La Farge’s style) surround the figures. Faces, hands, and feet were painted, probably by Juliette Hanson, one of La Farge’s key employees. In 1889 La Farge was awarded the French Legion of Honor for his contribution to the art of stained glass. Beautifully restored by Roberto Rosa and conservators at Serpentino Stained Glass Studio (see photo), these windows recover the sacred, revealing La Farge’s talent at its best.

Major support for restoration by Roberto Rosa at Serpentino Stained Glass Studio was provided by: Julia and James Alexandre, Sonja Calabi, Elaine Stein-Cummins and Daniel Cummins, C. Michael and Janet Daley, Mary Ann and Vincent Giffuni, Nancy and John E. Joyce, Susan Sloan and Arthur D. Clarke, Paul Stuka, Alison and William Vareika, and an anonymous donor.