Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Owens Valley, California, c. 1872

Oil on panel

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.44

Jeffery Howe

Professor Emeritus, Art History

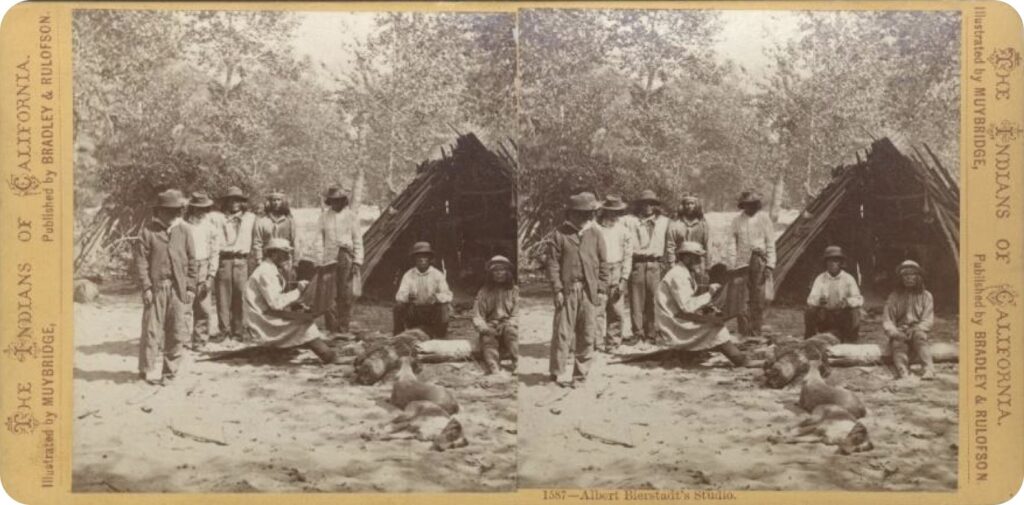

Bierstadt lived in California with a studio in San Francisco between 1871–73. He met the innovative photographer Eadweard Muybridge and traveled with him and the geologist Clarence King to the new Yosemite National Park in 1872. Muybridge photographed Native Americans and Bierstadt sketched the landscape and indigenous peoples. A stereoscopic photograph (see image) by Muybridge shows Bierstadt sketching out of doors, flanked by Native Americans.

The spectacular sunset over Mount Whitney is framed by the silhouetted trees in the foreground. Twilight brings a gentle end to the day in a scene that is now painfully nostalgic. The Owens River and Lake area, two hundred miles north of Los Angeles and near Death Valley, was famed for its wildlife, particularly migratory birds. The river was diverted to Los Angeles in 1913, crippling the agricultural economy of Owens Valley, and leading to the “California Water Wars” that provided the plot for the film Chinatown (1974).

Conevery Bolton Valencius

Professor, History

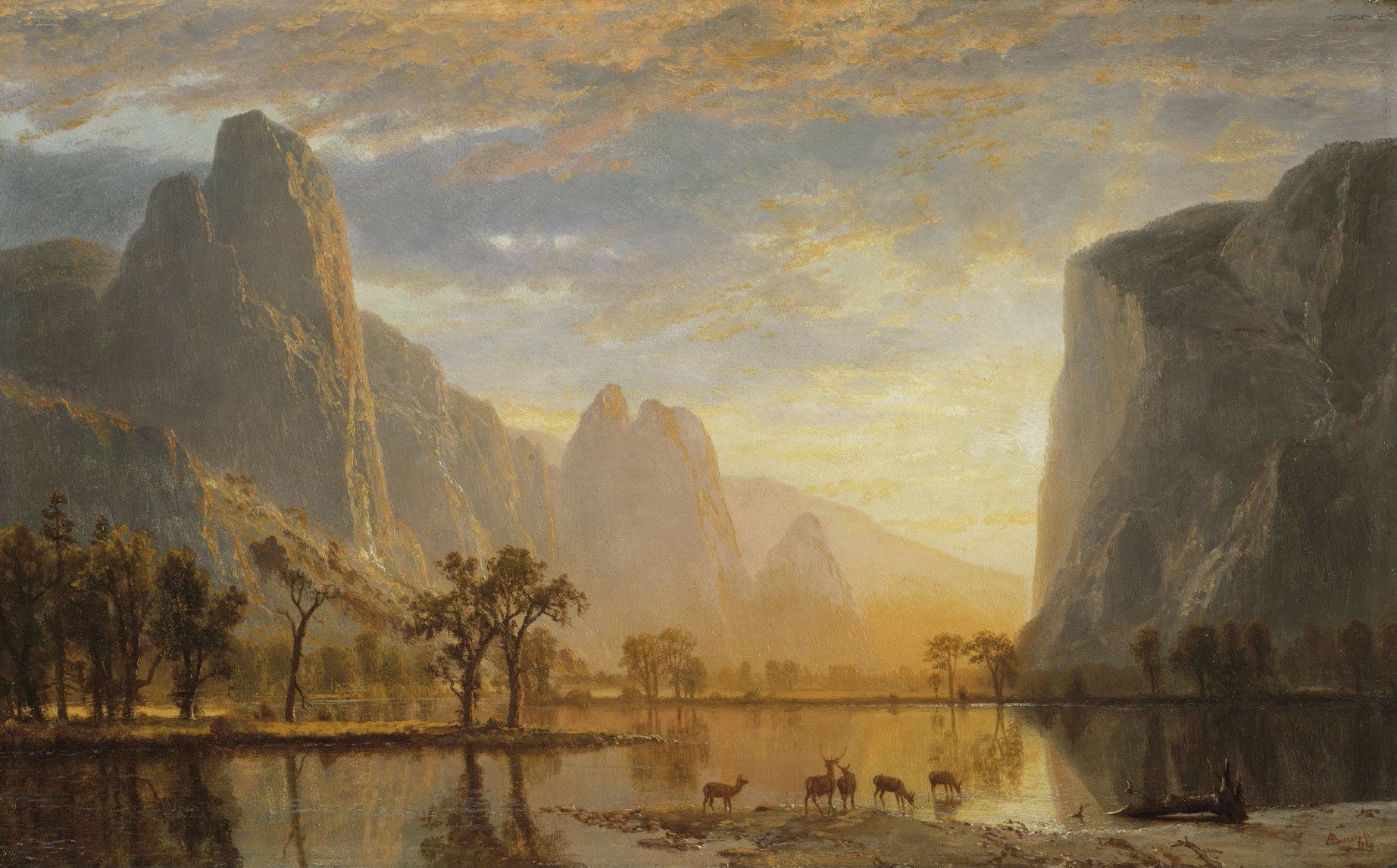

Albert Bierstadt’s portrayals of beauty and plenty shaped the popular image of the American West. Bierstadt reassured Americans wracked by civil war that their young democracy possessed the grandeur of Europe—and might endure just as long. His sublime, tranquil paintings of Yosemite Valley in 1864–65 (see images) are one reason the United States has a National Park Service. Yet just as the creation of national parks led to the dispossession of Native communities, Americans who flocked to western lands often utterly remade those landscapes. Still water fills Bierstadt’s 1872 image of California’s Owens Valley; evening light reflects over a lush lakeside scene. Yet by the 1910s, that Owens Valley water was being pumped hundreds of miles to slake the thirst of the booming new oil town, Los Angeles. Desperate landowners in the 1920s set dynamite blasts in a failed campaign to sabotage the pipeline with which LA was sucking their lake dry. Bierstadt’s skill captured the bountiful grace of a valley his art was helping transform.

With thanks for lively discussions in the Boston College History/Environmental Studies class “This Land is Your Land: A Survey of US Environmental History” as well as the Boston College Bodies & Places workshop.

Marilynn S. Johnson

Professor, History

Bierstadt traveled extensively out West in the summer of 1872, visiting Yosemite and the Owens Valley on the east side of the Sierra Nevada. In this painting, he captured the serene setting of the Owens Valley with the Mount Whitney mountain range in the background less than a decade after white wars against local Paiutes and Shoshone Indians opened the region for permanent white settlement. The work also offers a view of the valley wetlands some three decades before the city of Los Angeles would divert the Owens River for its own use, turning the area into a semi-desert. Like Bierstadt’s 1873 painting of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite (see image), which was later flooded by the city of San Francisco for a reservoir, his works show us the dazzling landscapes of the Sierra Nevada before they were transformed by urban demands for water in the arid West.

John Ebel

Professor, Earth & Environmental Sciences

Although Albert Bierstadt was born in Germany, he grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. He traveled extensively, returning repeatedly to Europe, where he had the opportunity to meet a number of internationally renowned figures. In Rome he and his wife visited the composer Franz Liszt, and in London he became acquainted with the American poet and educator Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. One of the most profound influences on his later work was a mountain climbing adventure in the Apennines, where, from above, he could observe the features of the mountainous terrain. This experience portended his engagement in producing paintings of mountain scenes, which became ever more enthralling as he traveled across the United States, painting in grand style the magnificent mountains, as in Yosemite, and the seemingly endless expanse of the prairies. To a friend he wrote: “The color of the mountains and of the plains, and, indeed, that of the entire country, reminds one of the color of Italy; in fact, we have here the Italy of America in a primitive condition.” Bierstadt traveled along the routes leading finally to California, and it was there that he produced his painting of Owens Valley. Even though the landscape itself is less than Italianate, the colors could indeed have reminded him of the light he had once observed in Italy—the reddish shades of dusk, the increasing darkness of the lake and the trees.

John Sallis

Frederick J. Adelmann, SJ Professor, Philosophy

Although Albert Bierstadt was born in Germany, he grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. He traveled extensively, returning repeatedly to Europe, where he had the opportunity to meet a number of internationally renowned figures. In Rome he and his wife visited the composer Franz Liszt, and in London he became acquainted with the American poet and educator Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. One of the most profound influences on his later work was a mountain climbing adventure in the Apennines, where, from above, he could observe the features of the mountainous terrain. This experience portended his engagement in producing paintings of mountain scenes, which became ever more enthralling as he traveled across the United States, painting in grand style the magnificent mountains, as in Yosemite, and the seemingly endless expanse of the prairies. To a friend he wrote: “The color of the mountains and of the plains, and, indeed, that of the entire country, reminds one of the color of Italy; in fact, we have here the Italy of America in a primitive condition.” Bierstadt traveled along the routes leading finally to California, and it was there that he produced his painting of Owens Valley. Even though the landscape itself is less than Italianate, the colors could indeed have reminded him of the light he had once observed in Italy—the reddish shades of dusk, the increasing darkness of the lake and the trees.

Noah Snyder

Professor, Earth & Environmental Sciences

Bierstadt’s painting of a silhouette of a pair of herons and trees with a twilit sky behind provides a glimpse of how this place looked before much of its water was diverted to irrigate the farm fields and orange groves of southern California and fuel the growth of Los Angeles. Owens Valley is still one of the most beautiful places on Earth, but it would be hard to recreate this scene, as many of these wetlands are now dry salt flats (see image). The position of the sun and the distant mountains suggests sunrise because Bierstadt does not depict the steep front of the Sierra Nevada, which defines the western side of the valley. Another interesting aspect to contemplate is that Bierstadt visited Owens Valley in summer 1872, just a few months after a major earthquake. Evidence of this event can still be seen today, as ridges that show the Sierra Nevada pushed twenty feet up relative to the valley floor along the fault line. The painting does not provide obvious evidence of the earthquake, but Bierstadt must have seen the aftermath in both the sparsely populated settlements and the natural landscape.