Orazio de Ferrari (1606–57)

Woman Taken in Adultery, c. 1639

Oil on canvas

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 1988.168

Stephanie C. Leone

Professor, Art History

Nothing is known about Woman Taken in Adultery prior to its display in Boston College’s Bapst Library in 1950, but its attribution to Orazio de Ferrari places it in the prosperous, mercantile, and international republic of Genoa, the first city in Italy to release its painters from guild membership. All of these characteristics fostered the city’s vibrant and pluralistic artistic culture.1 Orazio’s style draws upon that of his master Giovan Andrea Ansaldo (Voltri, 1584–1638), Flemish artists in Genoa like Anthony Van Dyck, Genoese painters Bernardo Strozzi (1581–1644), Giovanni Andrea de Ferrari (1598–1669), and Gioacchino Assereto (1600–49), and painters from other Italian schools. Despite this eclecticism, Orazio’s works are united by his commitment to naturalism.2

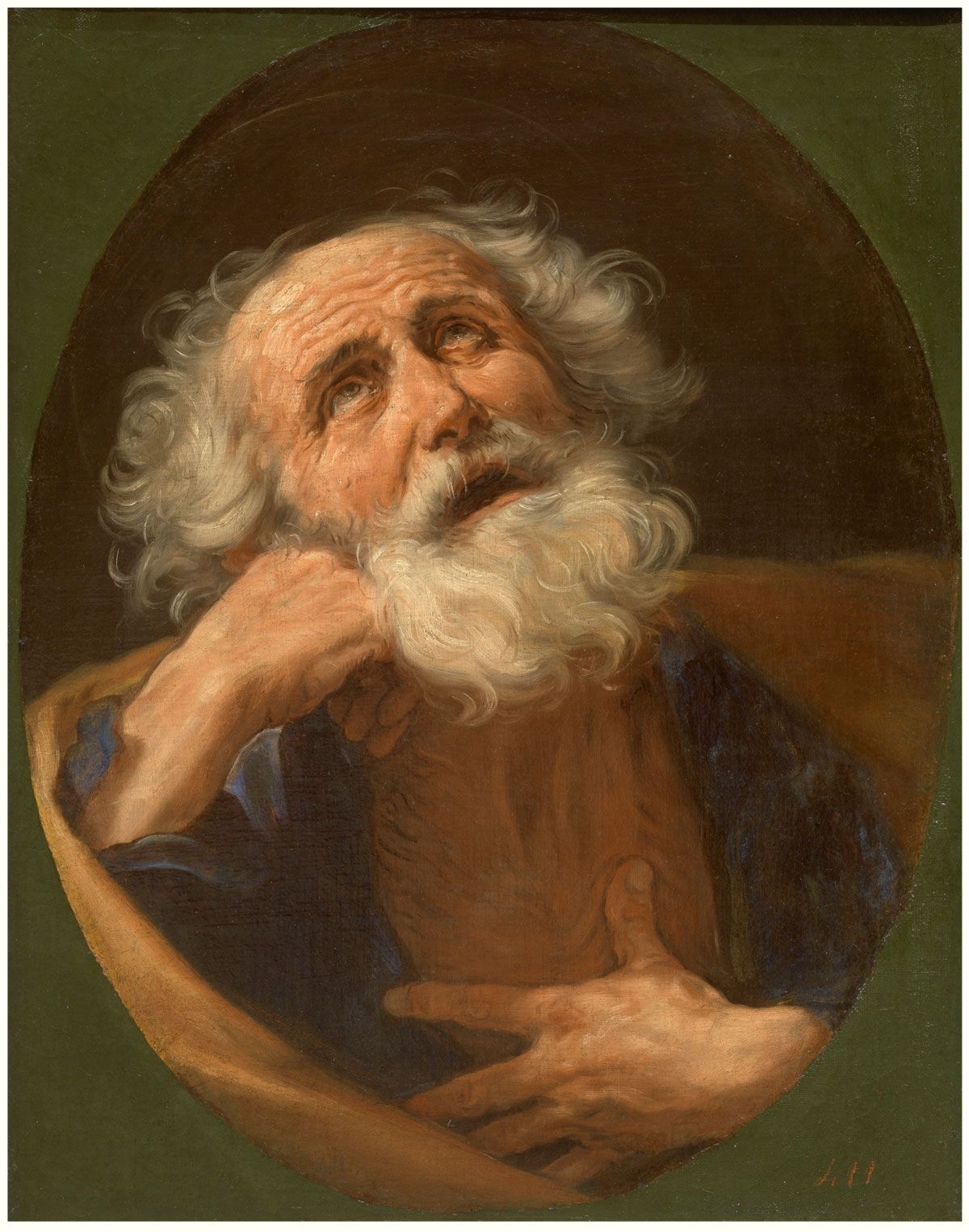

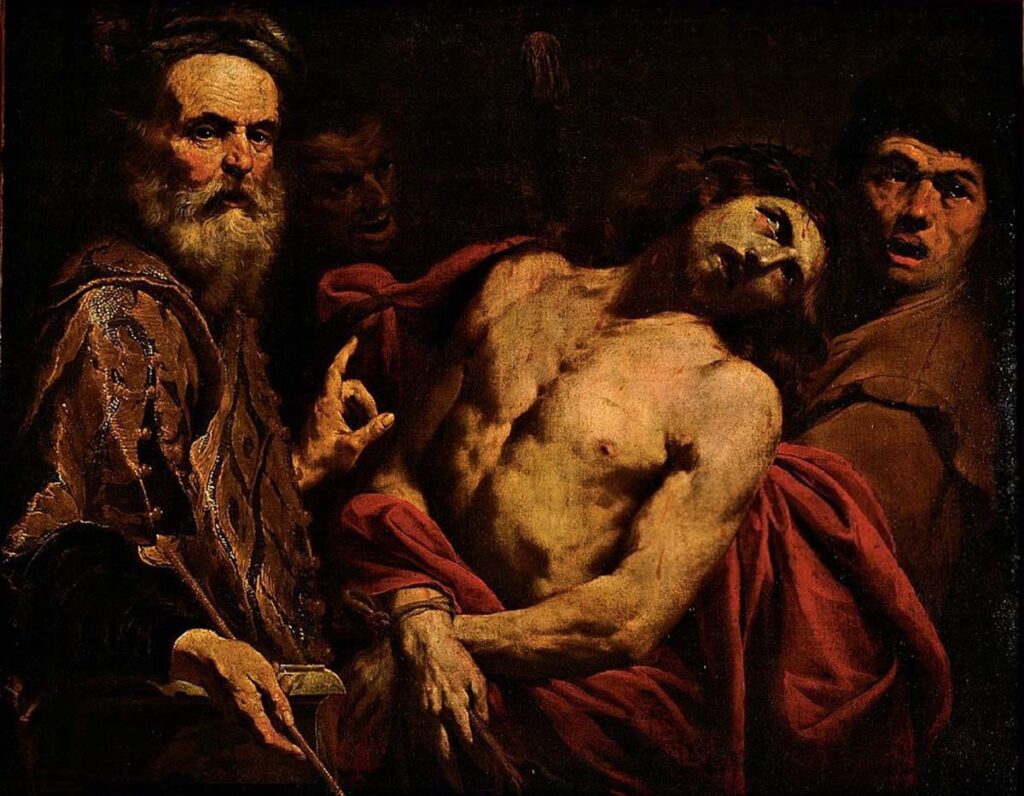

In Woman Taken in Adultery the artist’s observational tendency exemplified in the face of Christ and the head of the Pharisee is filtered through the lens of Guido Reni (Bologna, 1575–1642, see image). The elegant drapery of the adulteress reflects Ansaldo’s influence. These influences, along with the frontal composition, restrained postures, and limited spatial setting, suggest a work belonging to Orazio’s early phase (prior to 1639), exemplified by his Ecce Homo (see image).

Lacking the drama and spatial complexity of Orazio’s later works, the painting depicts a poignant scene of the Pharisee presenting the adulteress to Jesus (John 8:2–11). Rather than condemn the woman as expected, Jesus replied, “That one of you who is faultless shall throw the first stone,” and subsequently forgave her. Sin and forgiveness were central themes of seventeenth-century Catholic spirituality, and paintings like this one presented exemplars to inspire viewers to repent and seek the transformative power of God’s grace.3 Here the raking light moves from Jesus, across the face of the baffled Pharisee, to the adulteress, whose closed eyes and quiet gesture signify her imminent spiritual freedom. The horizontal format and the quotidian presentation of a Biblical scene are consistent with pictures intended to be hung in a palace, a destiny confirmed by the work’s elaborate, hand-carved frame. Orazio’s full-length version of the Biblical scene in Palazzo Bianco, Genoa (see image), suggests the success of this subject. In baroque Genoa, patrons competitively displayed art in their sumptuous homes to flaunt their wealth and status.

1. Jonathan Bober, Piero Boccardo, and Franco Boggero, eds., Superbarocco: arte a Genova da Rubens a Magnasco (Milan: Skira, 2021).

2. Franco Renzo Pesenti, La pittura in Liguria: artisti del primo seicento (Genoa: Cassa di risparmio di Genova, 1986), 433–87.

3. Thomas Worcester, “Trent and Beyond: Arts of Transformation,” in Saints & Sinners: Caravaggio & the Baroque Image, ed. Franco Mormando (Chestnut Hill: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 1999), 87–106.