Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Near the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains, 1863

Oil on panel

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.45

Jeffery Howe

Professor Emeritus, Art History

This idealized view of an unspoiled natural landscape, with a soft glow of the setting sun, beckons the viewer toward the Rocky Mountains while deer drink peaceably from a pristine lake. The artist juxtaposes the sublimity of the mountains with a vision of a rich and hospitable landscape seemingly fated for west-bound settlers, reflecting the concept of “manifest destiny.”

Bierstadt first traveled to the American West in 1859 as part of a survey expedition, followed by a second trip in 1863. He made oil sketches and drawings and chose views for stereographs. Bierstadt traveled as far as the South Pass of the Continental Divide in southwest Wyoming. The South Pass was the easiest route to California and the Pacific Northwest and had long been used by Native Americans. It was followed by wagon trains in the 1840s and 1850s as a key part of the Oregon Trail, and was the route of the transcontinental railway completed in 1869.

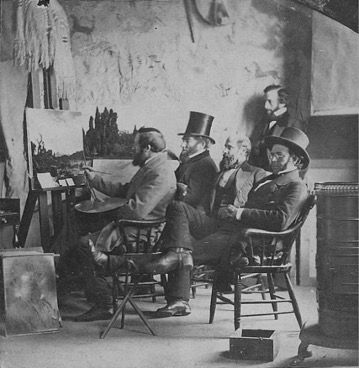

With notes and photographs, Bierstadt would later finish his paintings in his studio in the Tenth Street Studio building in New York City, surrounded by Native American artifacts (see image).

Marilynn S. Johnson

Professor, History

This work was created following Bierstadt’s first trip out West in 1859, when he accompanied Frederick W. Lander’s survey party to Nebraska Territory to determine the route of the transcontinental railroad. Bierstadt produced numerous photographs and sketches, which he then referenced in his New York studio. The South Pass was a significant locale where the Oregon Trail crossed the Continental Divide, a stretch that had tested numerous overland travelers. But by 1863, parts of the trail had been replaced by stagecoaches—and soon by the railroad. Paintings like this one invited his audience West in accordance with the idea of “manifest destiny” that envisioned white settlement of the West as inevitable and divinely ordained. His Romantic view of this Rocky Mountain landscape, with deer drinking from a luminous river, portrayed a timeless frontier that would soon be transformed.

John Sallis

Frederick J. Adelmann, SJ Professor, Philosophy

No landscapes were more compelling to Bierstadt than those he observed in the Rocky Mountains. Among his paintings of the Rockies, there are depictions of sublime, snow-capped peaks, of violent storms in the mountains, of the colorful glow of sunsets over the mountains, of peaceful lakes and woods backed by mountain ranges. Many prominent contemporary critics praised Bierstadt’s work; for instance, in response to one of the artist’s paintings of a storm in the Rockies, one wrote: “No more genuine and grand work has been produced in landscape art.” An art historian described Bierstadt’s paintings: “He seeks to depict the absolute qualities and forms of things. The botanist and geologist can find work in his rocks and vegetation. He seizes upon natural phenomena with naturalistic eyes. In the quality of American light, clear, transparent, and sharp outlines, he is unsurpassed.” The painting Near the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains depicts much of what belongs to a peaceful, natural landscape: distant, unthreatening mountains, rocks and trees as they occur by nature, untouched by human intervention, a pond reflecting muted sunlight, two deer next to the pond, one drinking from it. The work as a whole gathers all that belongs most conspicuously to nature—earth, water, living beings both animate and arboreal. Peter Lynch regards Near the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains as one of his favorites. He recalls that he was inspired to acquire it following one of his more than twenty-five visits to US National Parks with his wife and three daughters.