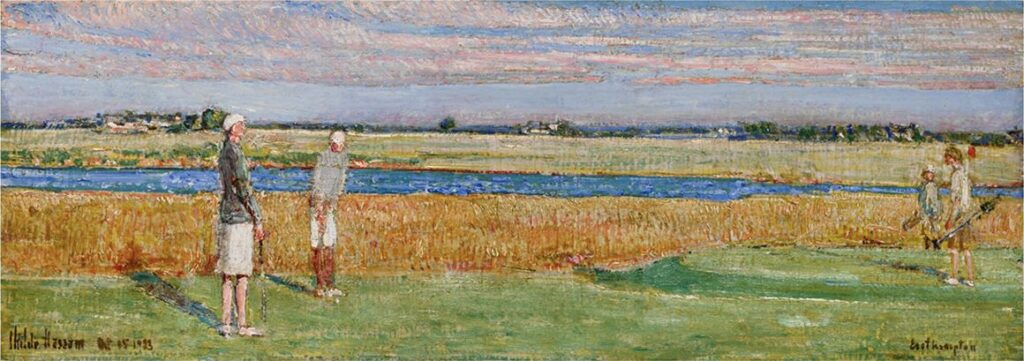

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859–1935)

Water Hazard—Maidstone Links, 1923

Oil on canvas

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.51

Oliver Wunsch

Assistant Professor, Art History

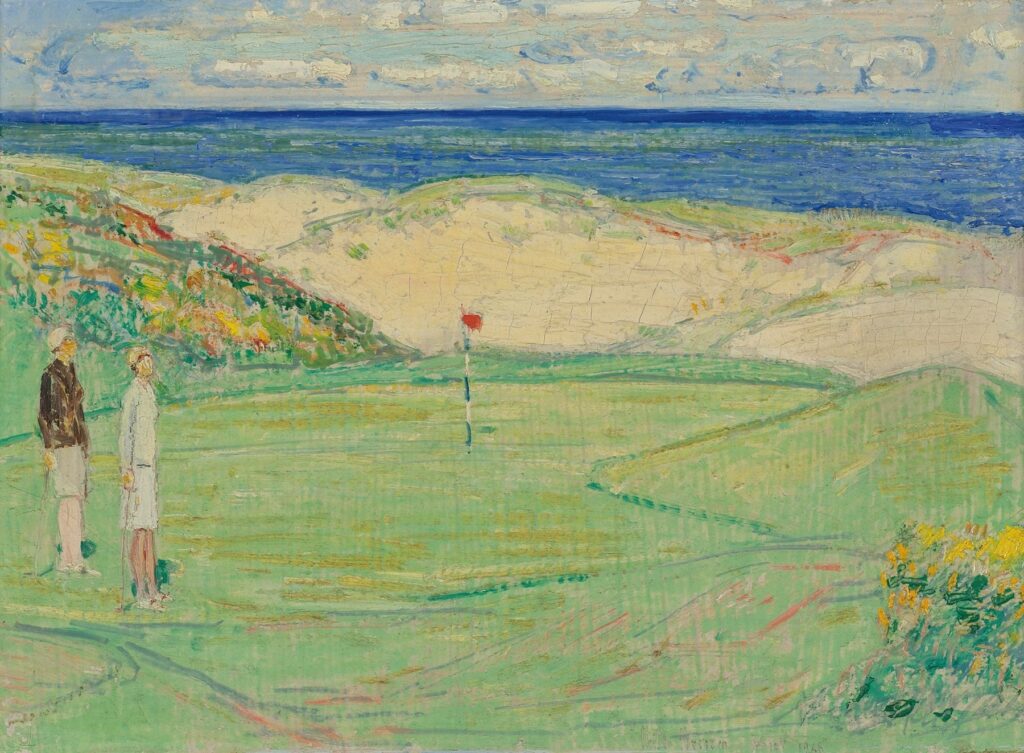

When Hassam made this painting, golf courses and country clubs were relatively new features of American life, constructed with Gilded Age fortunes and shaped by a nostalgia for the landscapes of British manor estates.1 Hassam himself was an avid golfer and member of the Maidstone Club on Long Island, which he used as the setting for multiple paintings (see images). Several of these works depict women golfers, whose presence in American country clubs attracted extensive social commentary at the time. Many writers argued that country clubs provided an unprecedented degree of female autonomy.2 “It has brought our women out of stuffy houses and out of their own hopeless, aimless selves,” Munsey’s Magazine declared in 1902.3 Women’s roles in country clubs, however, remained circumscribed; when golfing, they were frequently relegated to secondary courses or allowed to play the regular eighteen holes only after proving their skill, as was the rule at Maidstone.4

Hassam’s depiction of women golfers may have been driven less by an interest in changing gender norms than by his fascination with the female form in the landscape, which he regarded as an ancient subject. The statue-like rigidity of Hassam’s golfers and their arrangement in the flattened configuration of a frieze reflect Hassam’s efforts in the 1920s and 1930s to evoke the archaic forms of the Classical world.5 His attachment to ancient culture was intertwined with what Barbara Weinberg has described as his growing “xenophobia and nativism,” according to which modernism was the corrupt product of “foreign” influence.6 By this late phase in his career, Hassam denied his obvious debt to French impressionism, and he was fond of quoting the critic Royal Cortissoz’s denigration of modernist painting as “Ellis Island art.”7 The Maidstone Club, like many country clubs at the time, provided a hospitable environment for these views, codifying them in its membership policies (Jews were first admitted to Maidstone in 1976, and the club reportedly had no Black members into the twenty-first century8).

1. James M. Mayo, The American Country Club: Its Origins and Development (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

2. Mayo, American Country Club, 82–87.

3. Frank S. Arnett, “American Country Clubs,” Munsey’s Magazine 27, no. 4 (July 1902): 482.

4. Mayo, American Country Club, 99.

5. H. Barbara Weinberg, Childe Hassam, American Impressionist (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 244–46.

6. Weinberg, 18 and 244.

7. Hassam quoted in Weinberg, 18.

8. For the first Jewish members, see Paul Delaney, “Discrimination Remains a Policy and a Practice at Many Clubs,” New York Times, Sept. 13, 1976, 29; Steven Gaines, Philistines at the Hedgerow: Passion and Property in the Hamptons (New York: Little, Brown, 1998), 195. For the absence of Black members, see Bruce Weber, “Members Only,” New York Times, June 14, 1992, sec. Style, 10; Peter de Jonge, “Barbarian at the Tee: An Uninvited Non-Member Plays a Round at the Maidstone Club,” New York Magazine, Aug. 18, 2005.

John Ebel

Professor, Earth & Environmental Sciences

Two women with their young caddies are enjoying a round of golf on a beautiful summer’s day. One woman has just hit her tee shot and looks at the result of her endeavor. The other patiently waits her turn, club in hand. Hassam captures the natural beauty of eastern Long Island, New York, with a small pond guarded by a thick growth of reeds in the foreground and an expanse of grass and sand in the background. The women are dressed in the bright colors and styles of the 1920s, as are the caddies. The timeless beauty of this golf course is enjoyed today in much the same way as it was a hundred years ago.

Eileen Sweeney

Professor, Philosophy

With its explosion of color and visible separate brushstrokes, Water Hazard—Maidstone Links shows the strong influence on Hassam by the impressionists. Philosophical ideas about the relationship between sensation and concept formation illuminate the name “impressionism” as did Monet’s advice to students to paint what they see, not so much objects but patches of color, which we see enacted in Hassam’s work. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) argued that we take in raw sensation, for example, patches of color rather than fully formed objects, and only come to “see” things as distinct and three-dimensional objects by processing them, placing them in space (and time) and organizing them under concepts using reason. Moreover, Kant thought that the experience of pleasure in beauty is in the “play” of imagination and reason, using reason but not to organize impressions into fully formed defined objects, but rather to reflect back on the subject who sees and experiences. Hassam presents impressions of the scene on the links before they are turned into full-fledged objects, giving access to the naive sensations before they are processed. The grassy foreground is composed of disaggregated spots of color, while in the distance the color is blended into larger patches. According to Kant reason tells us that the grass we see in the distance is like the grass we see up close, that it is not really a single carpet of green but composed of multiple colors, but what we actually see, the sense impressions, in the distance is different from what we see up close, and this difference is what Hassam depicts. It is a new way of seeing that is both more “realist”—what we “really” see—and more “subjective”—about what is going on in the viewer’s mind, that brings us the pleasure in sensation itself, which is normally lost in the structuring and rationalization of experience.

Hassam paints a very ordinary scene from his present, not from history or allegory. Although playing golf requires wealth and privilege, he depicts the people here as ordinary, wearing basic golfing attire. It is a “modern” scene, where the women are playing the sport, attended by male caddies. Kant thought that we have to place the onslaught of sensation into three-dimensional space as well as into the sequence of time. This painting is of an unremarkable moment in time abstracted from any sequence without any evocation of a larger narrative. Nature rather than people was the most common impressionist subject, but here Hassam blends the people into the landscape. The landscape is not there to show them but vice versa. Hassam seems to have chosen to depict the people as “wooden” in an attempt to access sensation freed from concepts and three-dimensionality. In ordinary experience, visual data is subsumed under concepts—man, woman, male, female—and the visual details fade into that whole. We only see one side of an object and reason supplies the sides and the back, their three-dimensionality. Hassam brings us back to the experience of the human figures as bright and vibrant patches and dabs of color, flat rather than rounded. He focuses on the surface and patterns on their clothing, rather than on their depth. The depiction of the players is detached and also takes steps toward abstraction as they are rendered as shapes and patterns, and as elongated and still. The movement in the painting comes from the beautiful grasses on the shore on the bottom right that bend in the breeze.