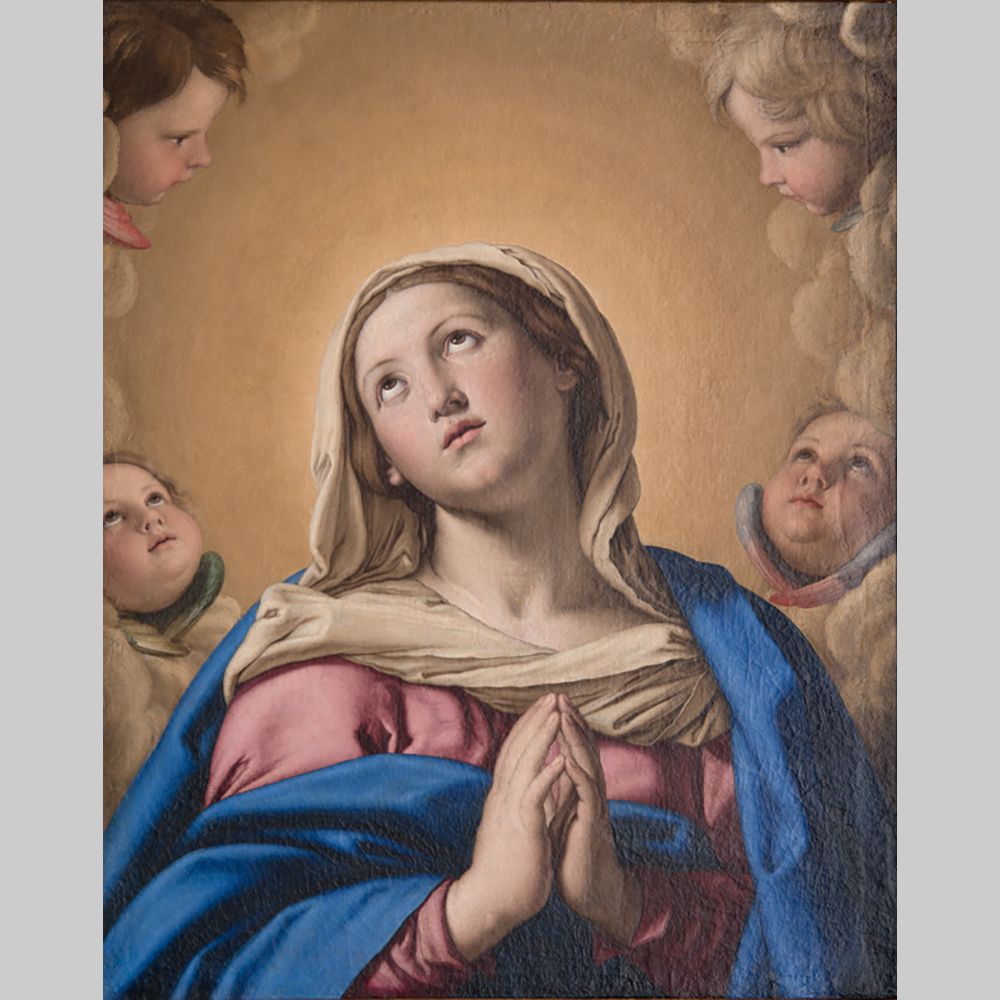

Giovanni Battista Salvi (Sassoferrato) (1609–85)

Madonna of the Cherubs, c. 1650

Oil on canvas

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 1988.72

Stephanie C. Leone

Professor, Art History

Framed by the cherubic messengers and the golden light of heaven, the Virgin Mary gracefully shifts her shoulders and lifts her head, eyes, and—we sense—mind to God. The rotation is stilled by her praying hands that gently stabilize her figure and crystalize her complete devotion. The brushstrokes of oil paint are applied smoothly to form the perfect contours of her face, and earth pigments are blended into her creamy-rosy complexion to depict soft shadows. The texture of the drapery is slightly rougher, hinting at the material world. Mary is at once corporeal and ethereal, the perfect embodiment of the union between the sacred and the earthly in the mother of God.

Born in the rural region of the Marche, northeast of Rome, Giovanni Battista Salvi, known as Sassoferrato after his hometown, was out of step with the exuberant baroque art of his time, but his paintings tell us much about Catholic devotional culture. He formulated a unique style through studying the Renaissance painters, Perugino, Andrea del Sarto, and especially Raphael, and classically minded seventeenth-century painters, such as Domenichino and Guido Reni, but restrained their palettes, compositions, and sense of energy. Sassoferrato dedicated himself to making images of the Virgin Mary. He developed a handful of types and repeated the compositions with small variations. At the time of his death, his inventory recorded 105 paintings in his possession, of which seventy were Madonna images.1

As a Boston College undergraduate, Christine Papastamelos ’14, interpreted Sassoferrato’s Madonna of the Cherubs in the context of the Catholic Reformation: “The image of Mary as heaven bound and without child epitomizes the [Catholic] Marian theological position of the seventeenth century.” The painting celebrates Mary’s essential role in salvation and the grace that God uniquely bestowed upon her. Sassoferrato’s Madonna of the Cherubs is a short-hand version of the iconography of the Immaculate Conception, the belief that the Virgin Mary was exempt from original sin. Due to its size, the painting most likely functioned as a devotional work in a private setting, in comparison to Reni’s full length Conception (see image) that codified this iconography.

Sassoferrato’s Madonnas appealed to the Catholic faithful during his own day as well as succeeding centuries, with numerous popes prizing his paintings. Pius VII (1800–23) had a print made of his Madonna in Prayer to disseminate the image widely. The provenance of Boston College’s painting is unknown until 1947 when it was recorded in a photograph of Bapst Library.

Praying hands were a key motif for Sassoferrato, and the McMullen Museum owns his drawing of this theme.

1. Patrizia Cavazzini, “L’inventario della morte di Sassoferrato e il problema delle copie,” in Sassoferrato, Pictor Virginum: Nuovi studi e documenti per Giovan Battista Salvi, ed. Cecilia Prete (Ancona: Il lavoro editoriale, Istituto Internazionale di Studi Piceni, 2009), 56–69.