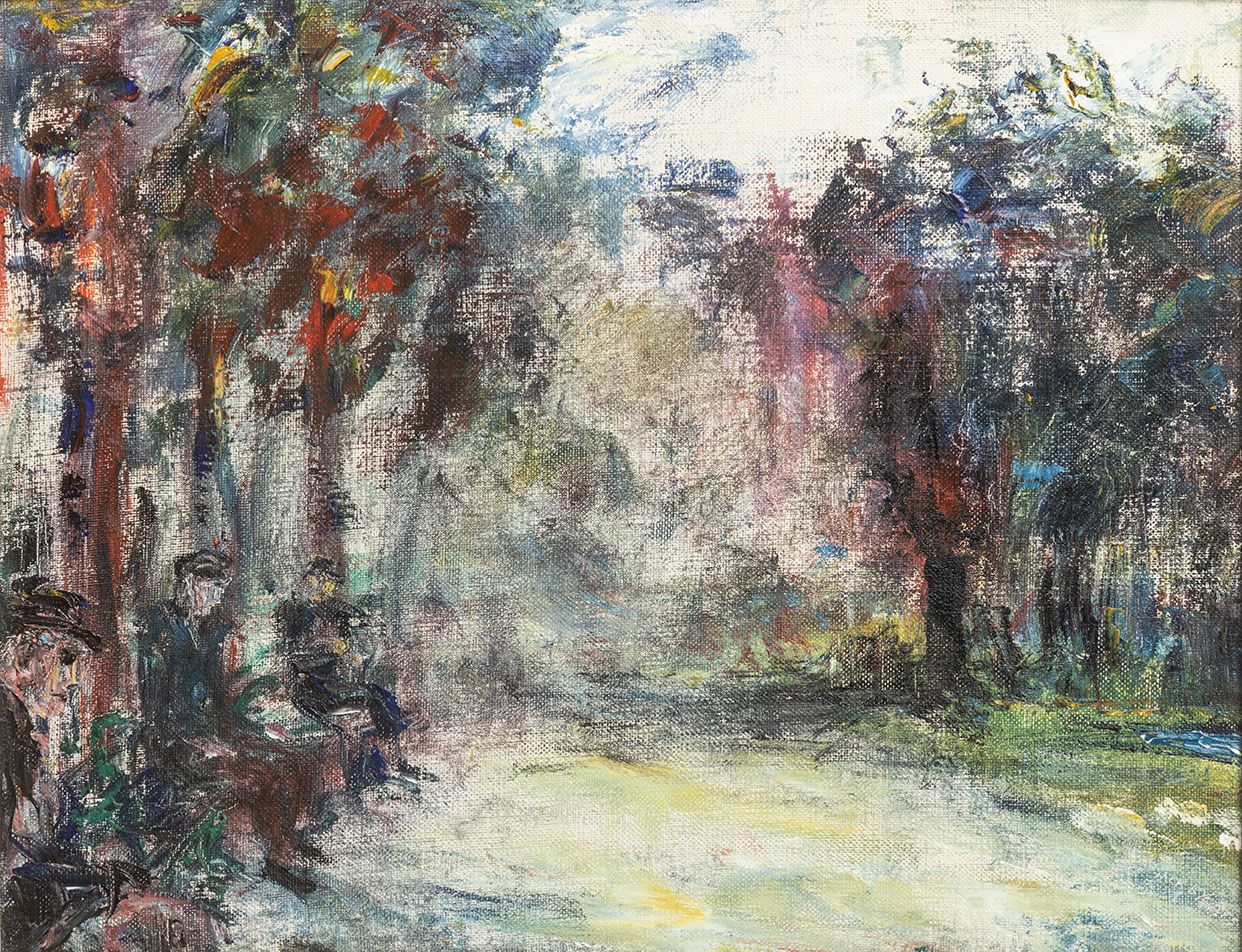

Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957)

Quiet Men, 1946

Oil on canvas

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.61

Kevin Lotery

Assistant Professor, Art History

Painted during Jack B. Yeats’s productive later years, Quiet Men evinces an artist clearly focused on exploring, and ultimately undermining, the discipline of painting, its most privileged genres, materials, and techniques. The work likely depicts a line of solitary figures, taking up their daily posts on the benches of St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin.1 Performing a more or less common ritual at the time, these quiet figures could, from this vantage, take in the everyday life of their city and no doubt ponder, like Ulysses (1922) protagonist Leopold Bloom, the intersection of the banal and the epic. A fellow Irish writer and theorist of exile and dislocation, James Joyce (1882–1941) was in fact one of Yeats’s most abiding admirers. “Jack Yeats and I have the same method,” he once supposedly stated, cryptically.2 What is meant here by “method” remains an enigma, but we might offer some guesses by looking closely at Yeats’s surfaces, where representation finds itself given over to the abstract materiality of paint, performing microscopic interactions of color, liquidity, and canvas.

These materialist explorations possess a critical edge, as if to negate and refuse painting’s most privileged act, the application of paint to canvas. The British critic John Berger (1926–2017) once speculated that Yeats may have, at times, abandoned the hallowed tool of the easel painter, the paintbrush, in favor of simply smearing paint onto canvas directly from the tubes themselves, using the “nozzle” as a means of mark-making.3 Yeats, then, brought his painterly degradation both to the tools and to the very hand of the painter—that privileged seat of academic skill and personal expression. Negating it in favor of the commoditized, ready-made tube of paint, Yeats’s marks separate themselves from the hand of the master, declaring themselves as mere matter, no more or less privileged than the wet mud or dispersing fog that we see in Quiet Men. This is classic Bloom, whose epic journey unfolds over the course of a single, banal summer’s day in Dublin. Finding himself formed and reformed by a collage of literary styles spanning the history of the English language, Bloom moves from human protagonist to microscopic “speck” to mere emanation of linguistic material. At his core, Bloom is an absence, like the barely pigmented nothingness at the center of Yeats’s picture.

1. See Hilary Pyle, Jack B. Yeats: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, vol. 3 (London: Deutsch, 1992), 670.

2. Quoted in Colm Tóibín, Colm Tóibín, “The Unmapped Space: Memory in Yeats, Joyce, and Beckett,” in Jack B. Yeats: Painting and Memory, ed. Donal Maguire and Brendan Rooney (Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland, 2021), 19. See also Richard Ellman, James Joyce (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 715.

3. John Berger, “The Life & Death of an Artist” (1960), in Jack B. Yeats: A Celtic Visionary, ed. Howard Smith and Stephen Snoddy (Manchester: City Art Galleries, 1996), n.p.

Marjorie Howes

Associate Professor, English & Irish Studies

His childhood in the West of Ireland gave Jack Yeats the subject matter that dominated his artistic life. His representations of rural people he saw there often invite conflicting interpretations. He was sympathetic to Irish republicanism, both before and after the War of Independence, and some observers have suggested that Yeats, like certain members of the Irish Literary Revival, had a tendency to idealize the Irish peasantry. Others have argued that his work emphasizes the mystery and dignity of his subjects and foregrounds the difficulties of representation. This enigmatic expressionist oil from his later period embodies such ambiguity. The title may invoke Maurice Walsh’s short story “The Quiet Man,” which was first published in 1933 and became famous for its depiction of an Irish countryman as the strong, silent type who is capable of explosive violent action. It was later adapted into John Ford’s iconic film The Quiet Man, starring John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. The “quiet men” in this painting can be interpreted along these lines as Irish people, even Irish revolutionaries, whose stillness belies their capacity for movement or violence. On the other hand, they are consigned to the margins of the scene and threaten to disappear into the similarly colored background or fall out of the frame altogether. The center of the painting is both filled with light, in contrast to the darkness of the men, and eerily empty, suggesting limits on what the viewer can see.