Welcome to the mobile guide to selections of the McMullen Museum of Art’s permanent collection on view on the first floor of 2101 Commonwealth. You may use the QR codes on each work’s label to access its commentary, or you may select from the list below.

This index is organized by room name and number. Works in the Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection also have their own index, viewable at this link.

- First floor corridor south

-

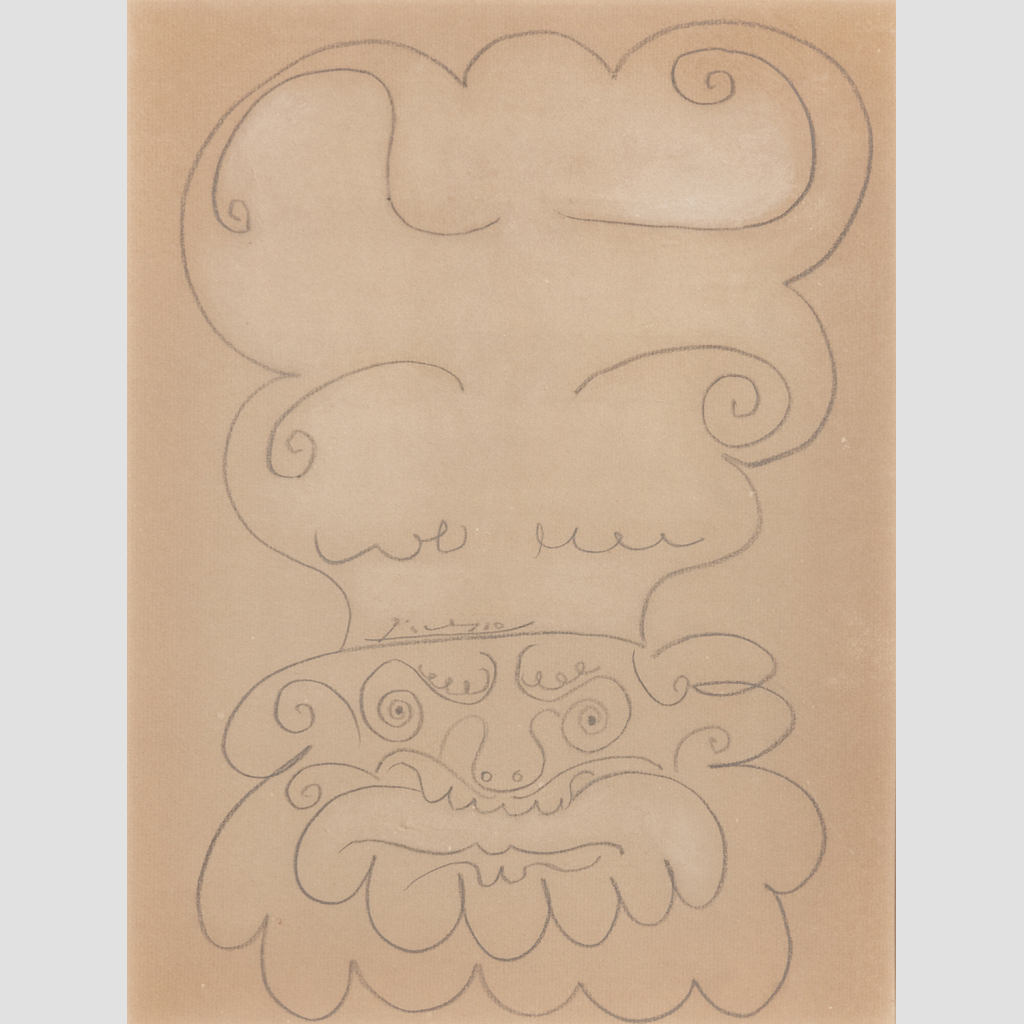

Pablo Picasso

L'homme barbu (Bearded Man)

-

William Stanley Haseltine

Rocks at Narragansett

-

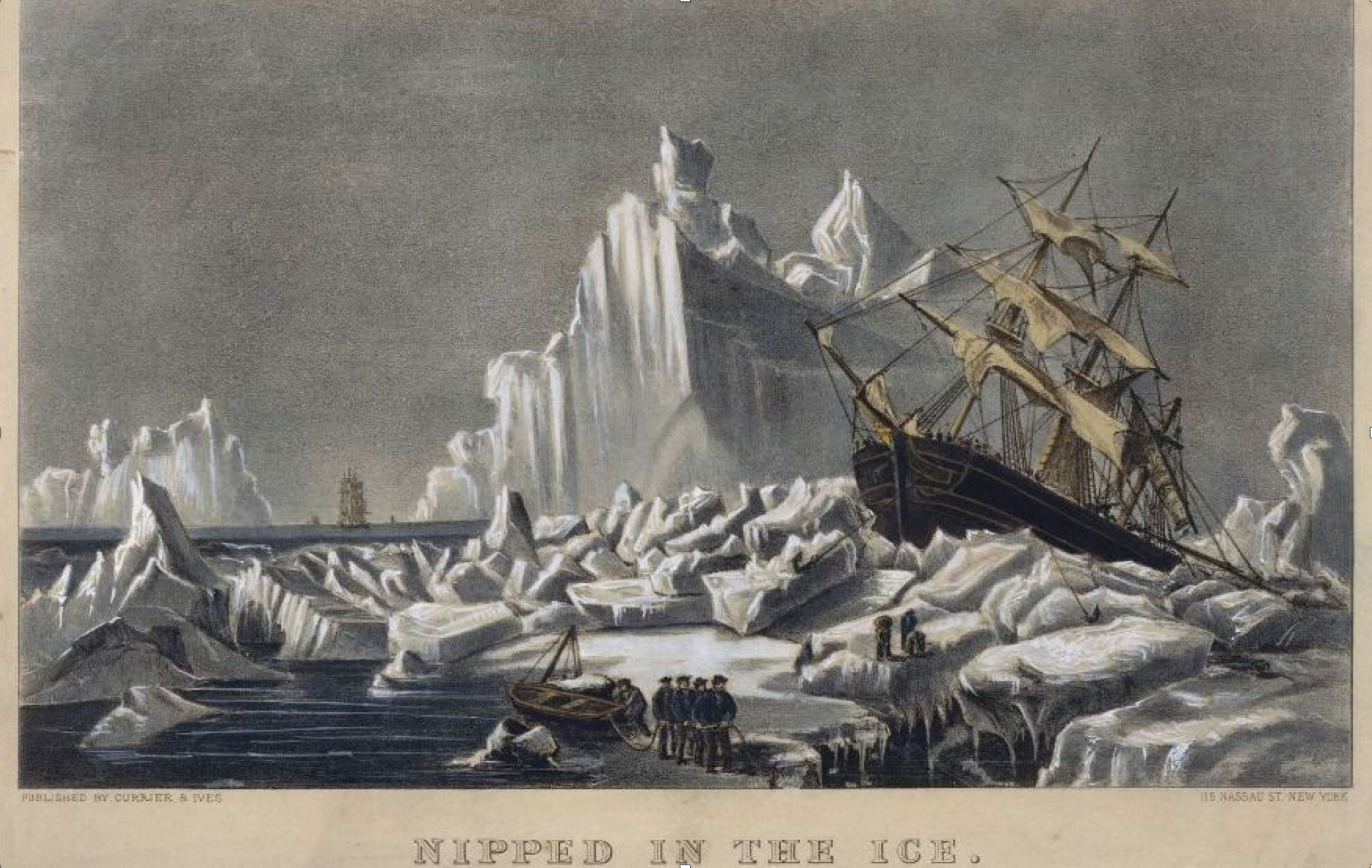

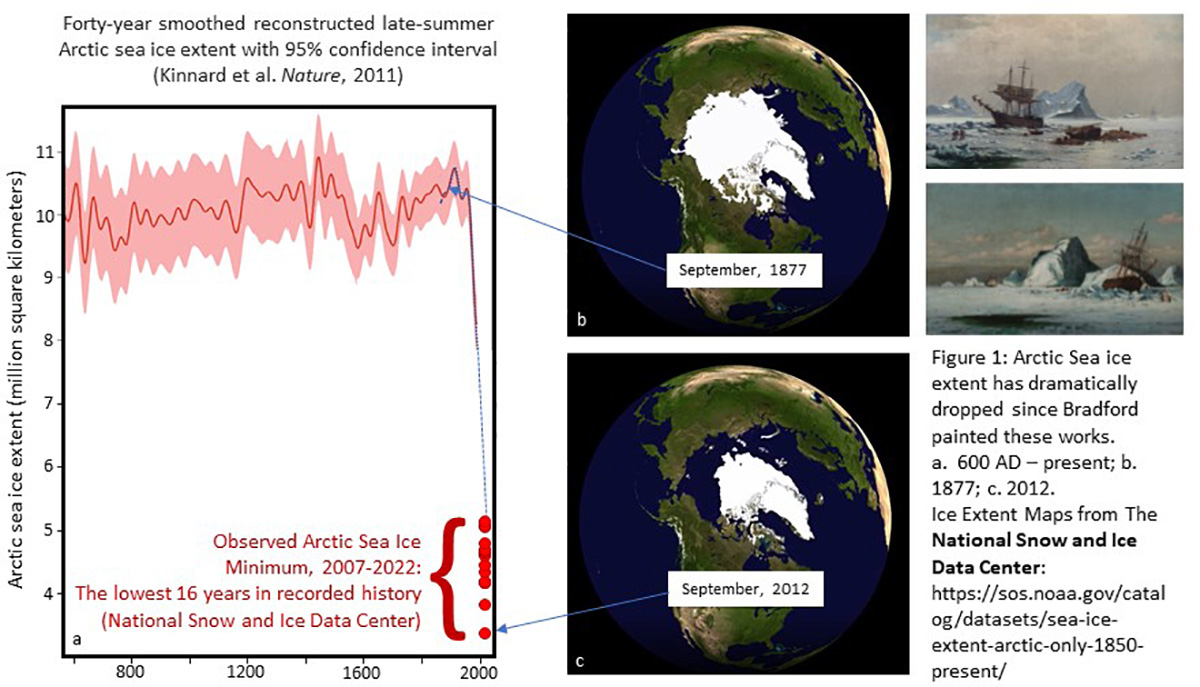

William Bradford

Trapped in Packed Ice

-

John Singer Sargent

Study of a Fig Tree

-

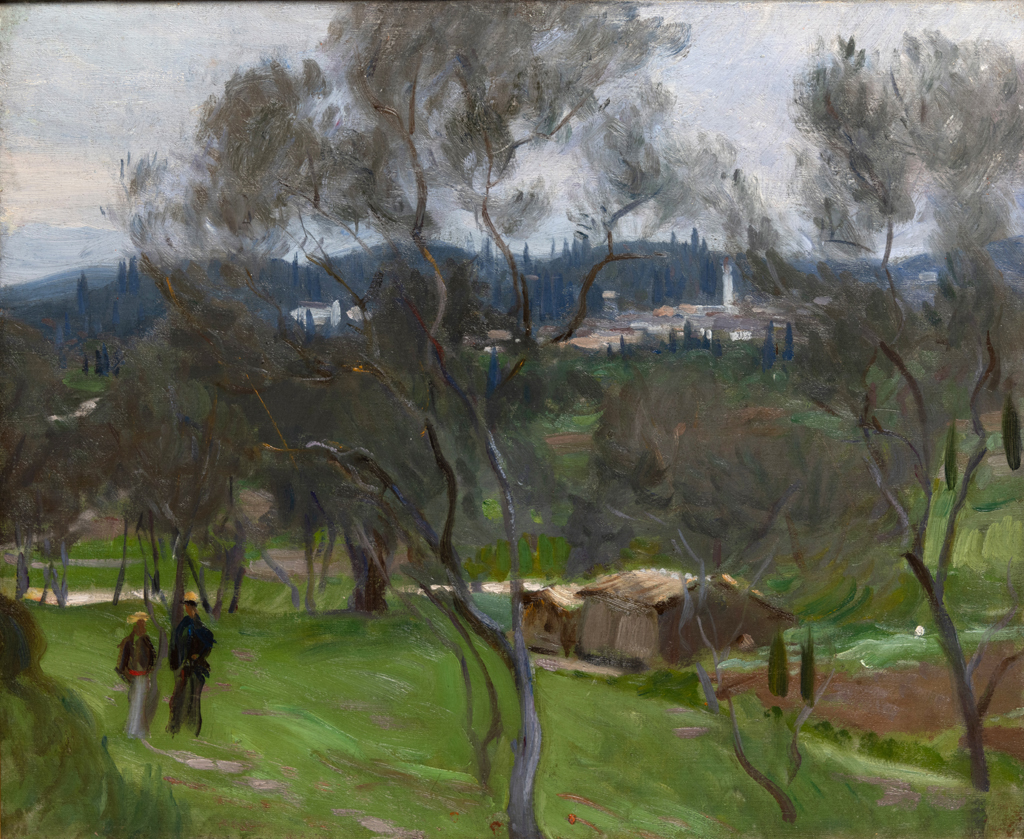

John Singer Sargent

Olive Trees, Corfu

-

William Bradford

Coastal Scene with Figures (Grand Manan)

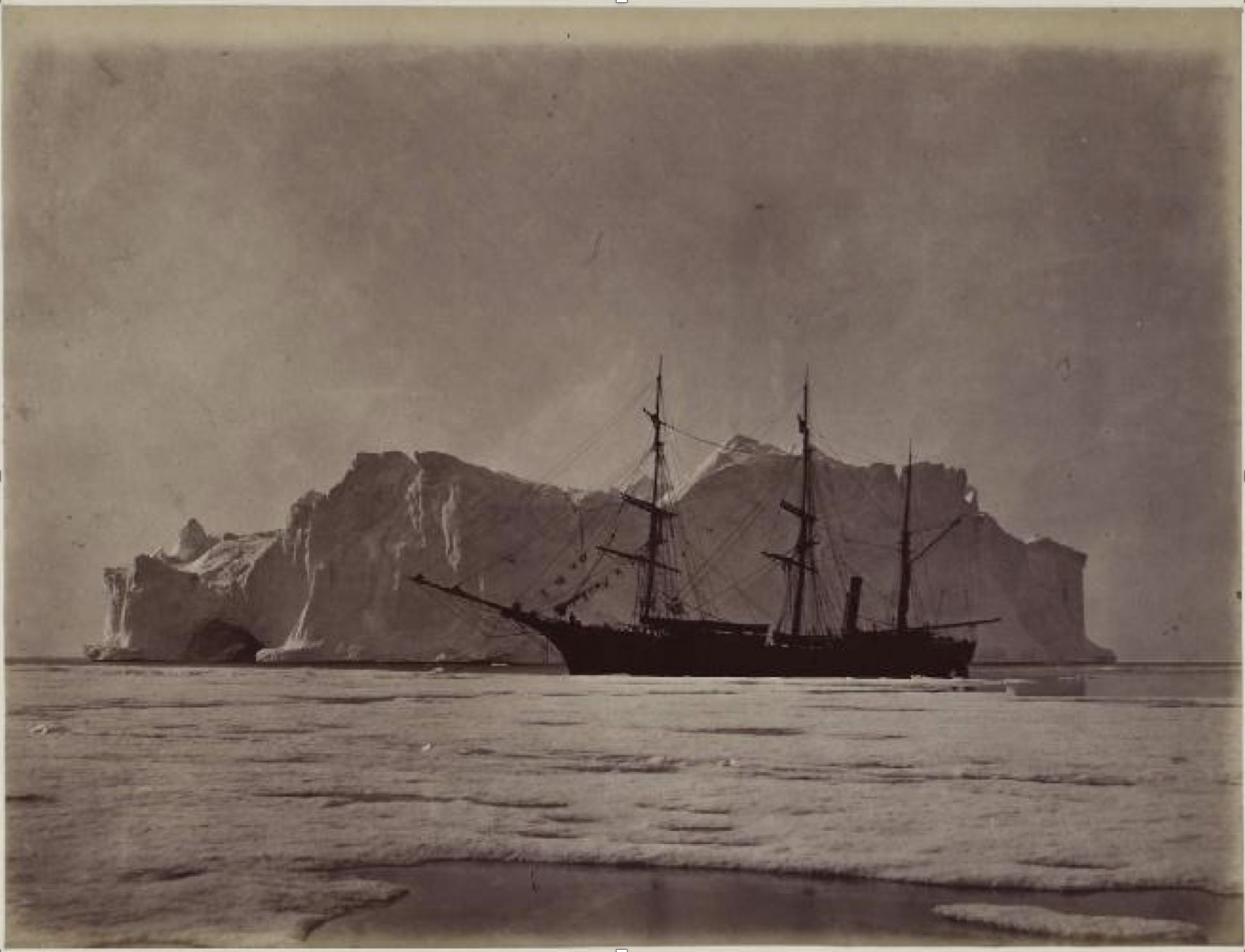

William Bradford

Among the Ice Floes

-

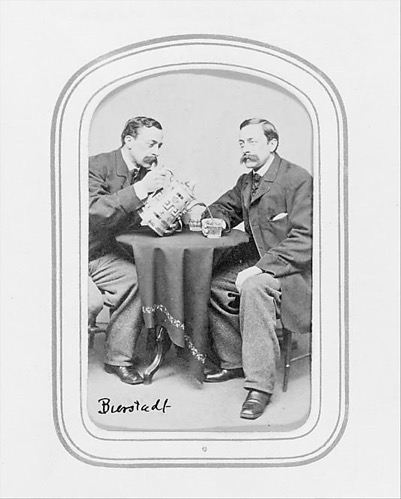

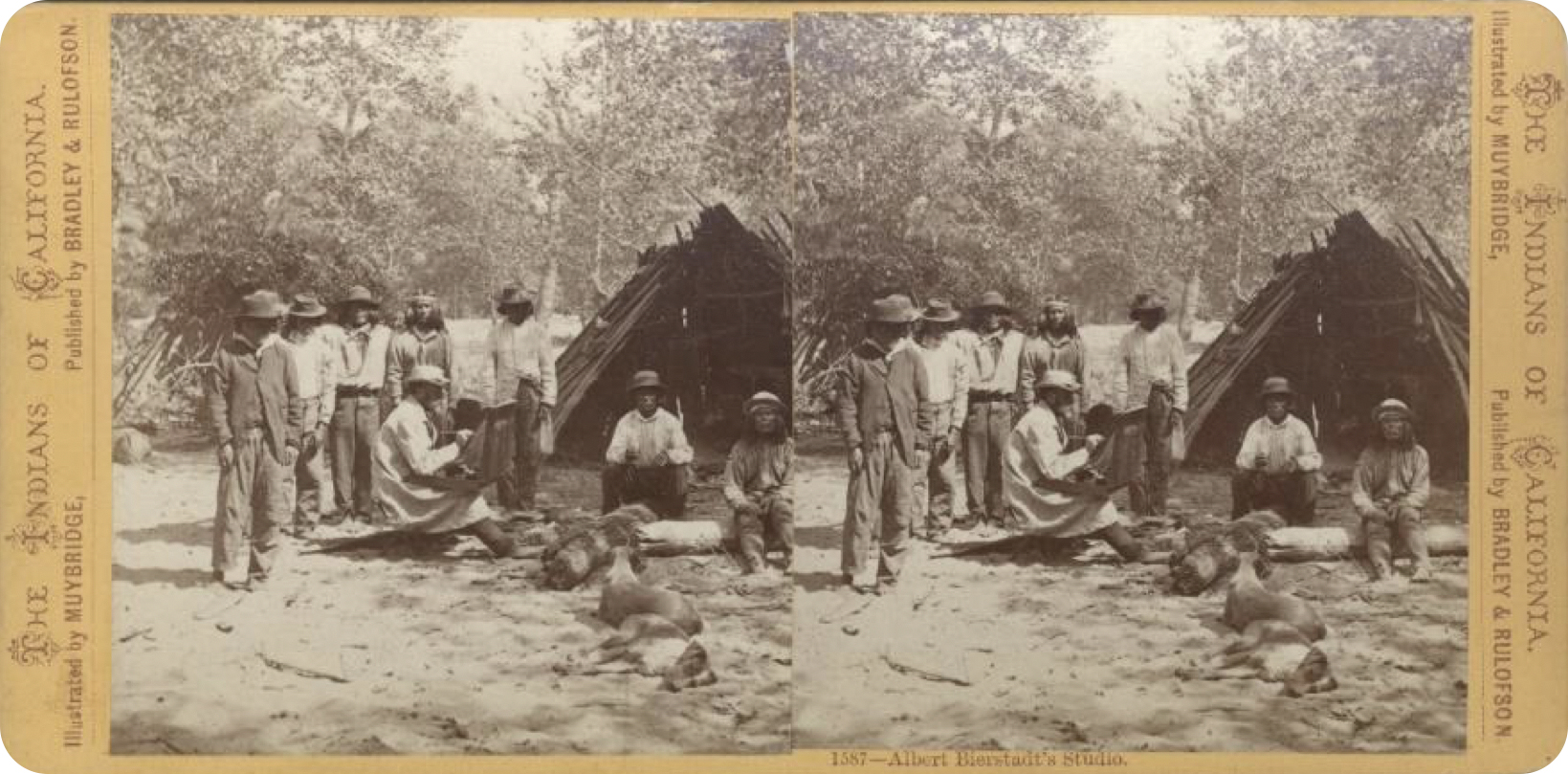

Albert Bierstadt

The Approaching Storm: White Mountain View with Hay Wagon and Figures

-

John Frederick Kensett

On the Beverly Coast

-

Albert Bierstadt

Newport Rocks

-

Francis Augustus Silva

Approaching Storm

-

George Inness

In the Evening

- First floor corridor north

-

James Miller

Peaceable Kingdom

-

Winslow Homer

Grace Hoops

-

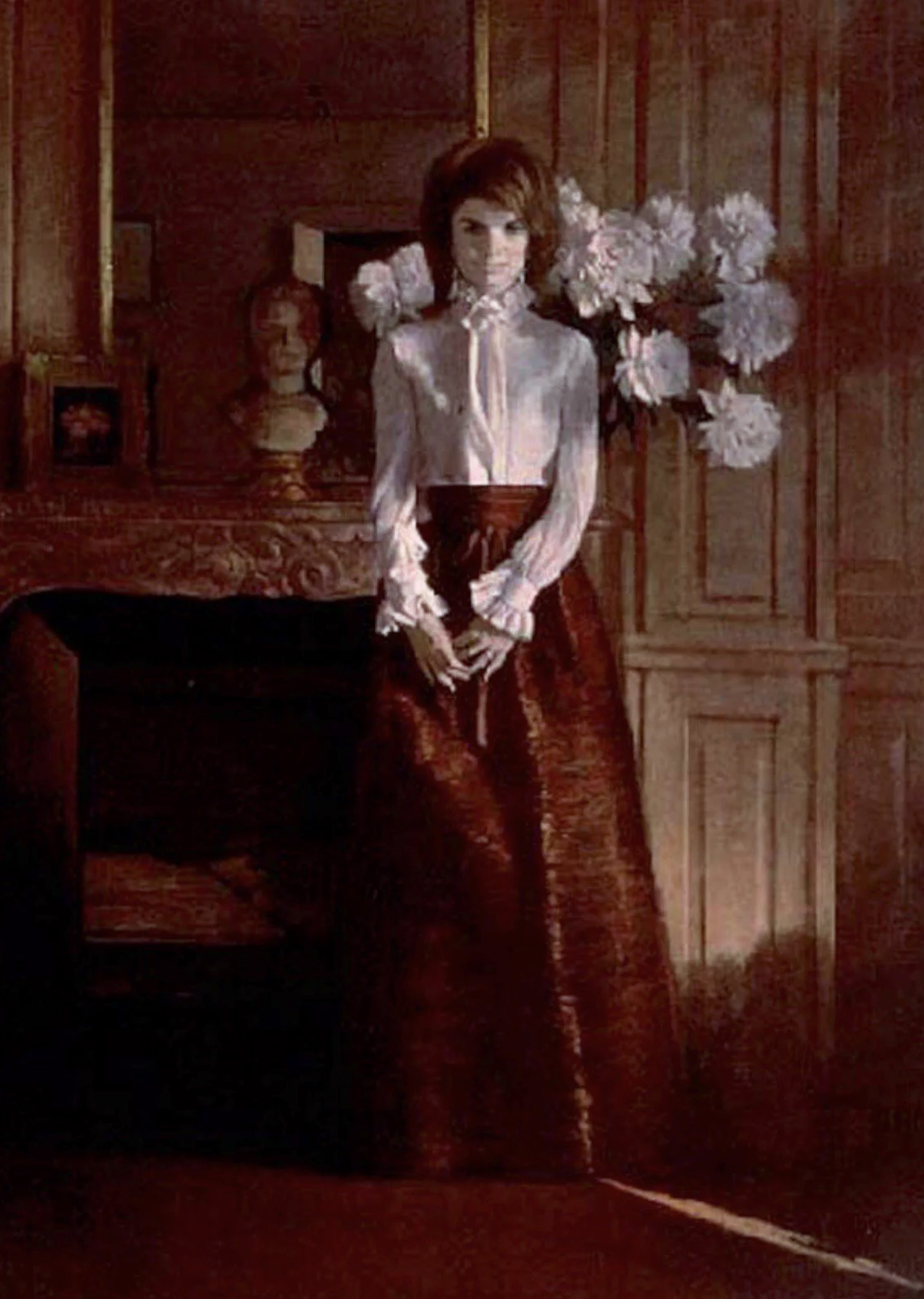

Aaron Shikler

Study for the White House Portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy

-

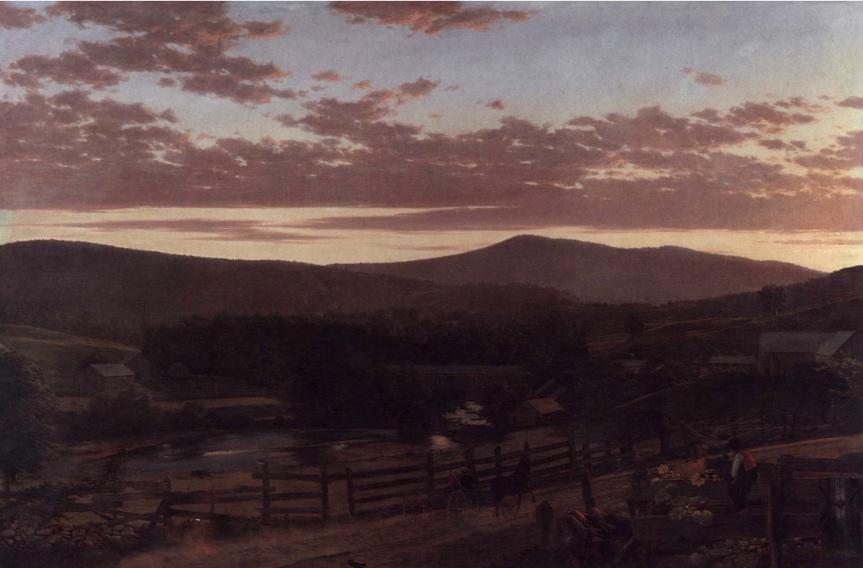

Frederic Edwin Church

New England Landscape

-

William Stanley Haseltine

Coast near Rome

-

Mary Stevenson Cassatt

Mother and Child

-

Diego Rivera

Family

- Entry area

-

James Edward Buttersworth

Racing Yachts

-

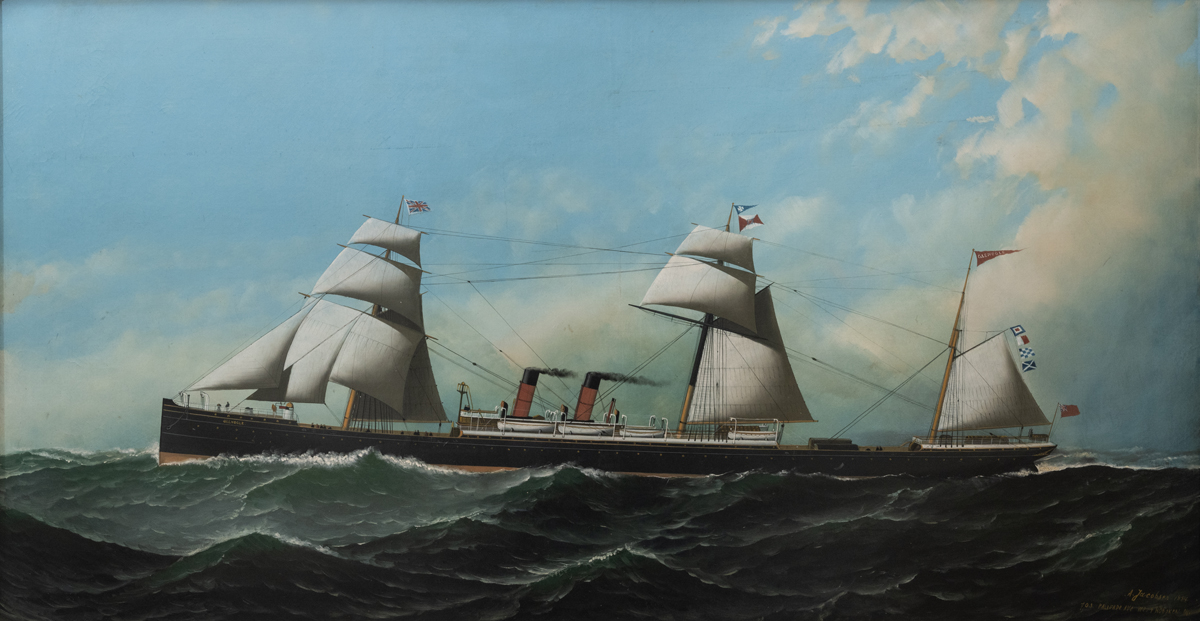

Antonio Nicolo Gasparo Jacobsen

SS “Commonwealth”

-

Antonio Nicolo Gasparo Jacobsen

SS “Glenogle”

-

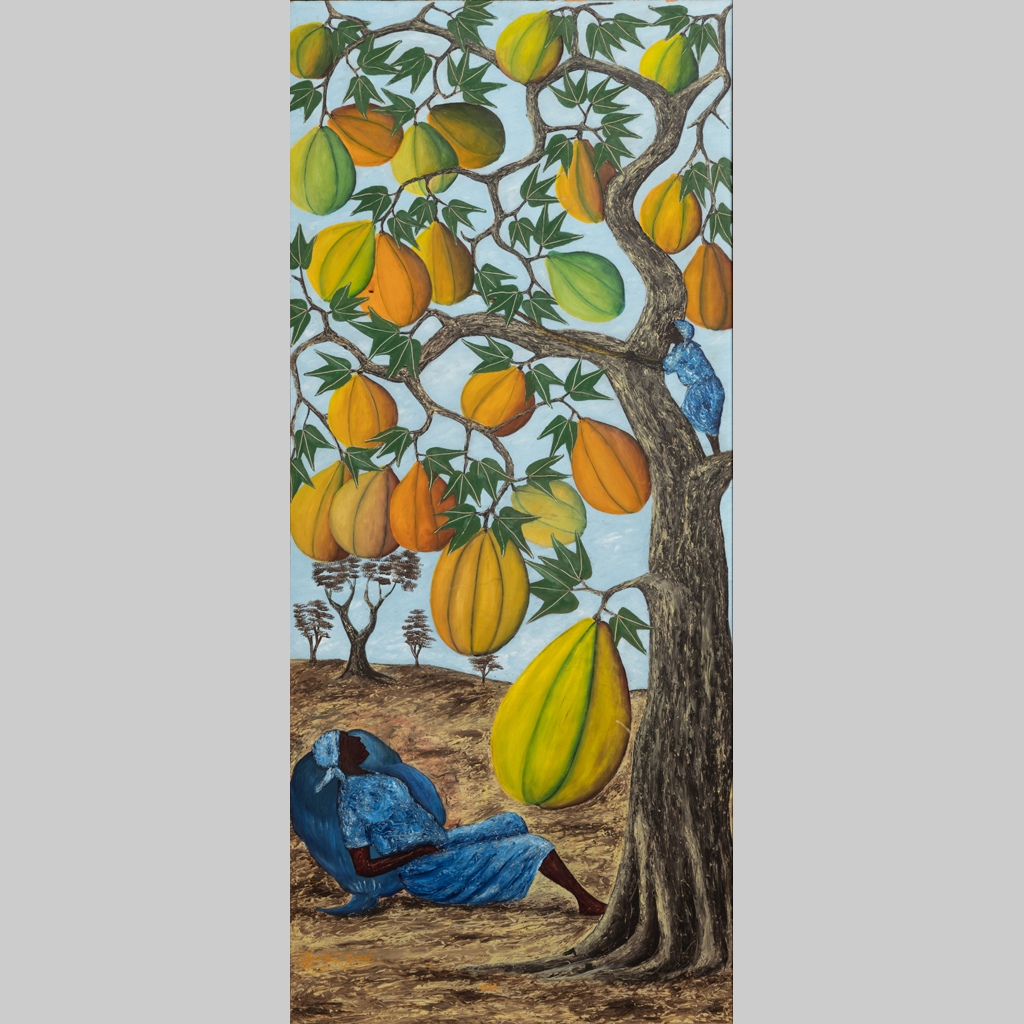

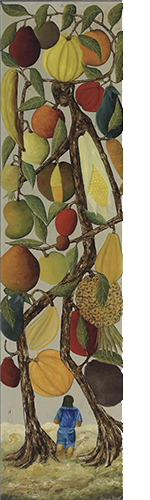

Jasmin Joseph

Landscape with Gourds

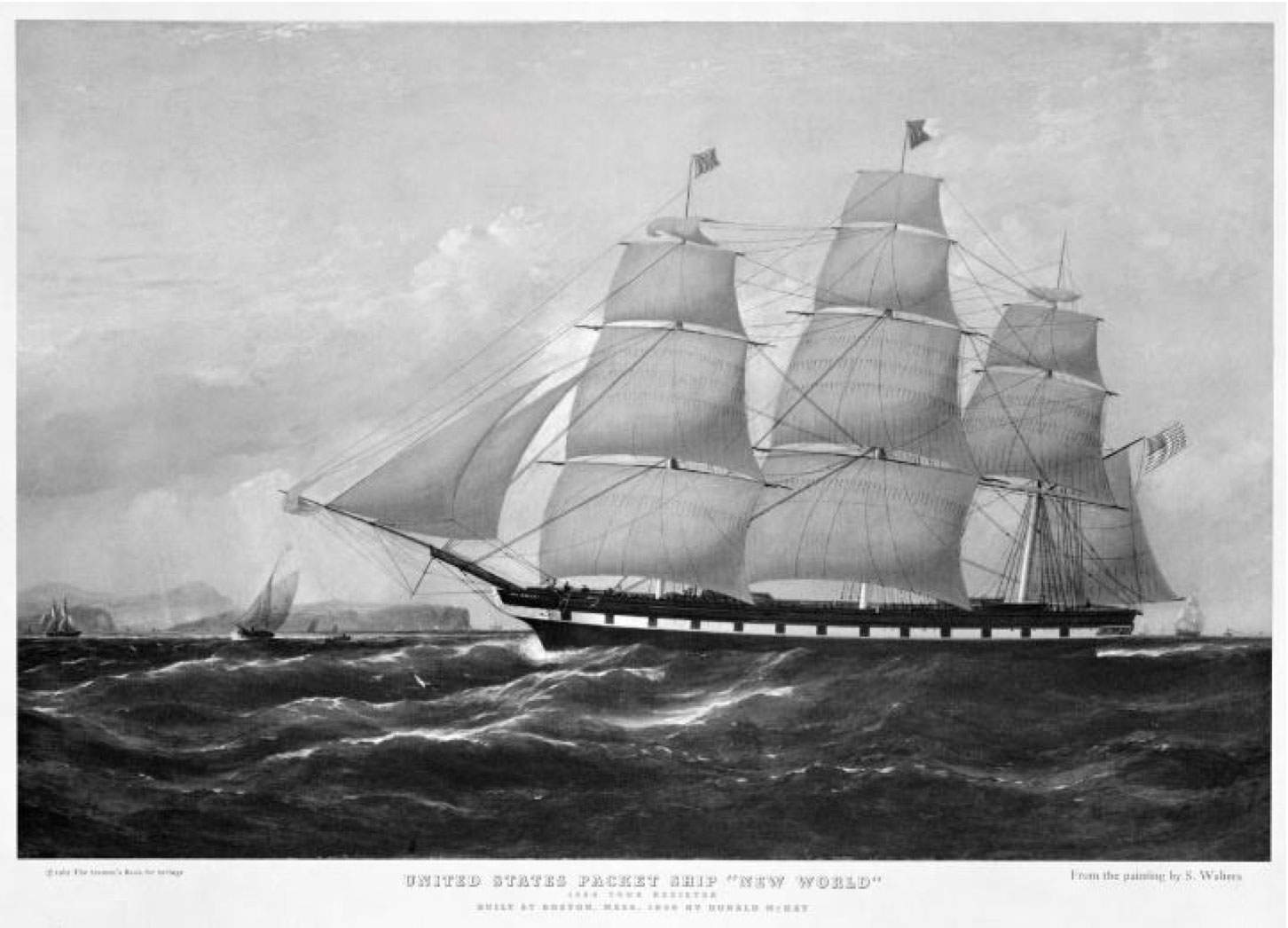

Samuel Walters

“Aurora”

- Casimir-Lambert Conference Room (Room 104)

-

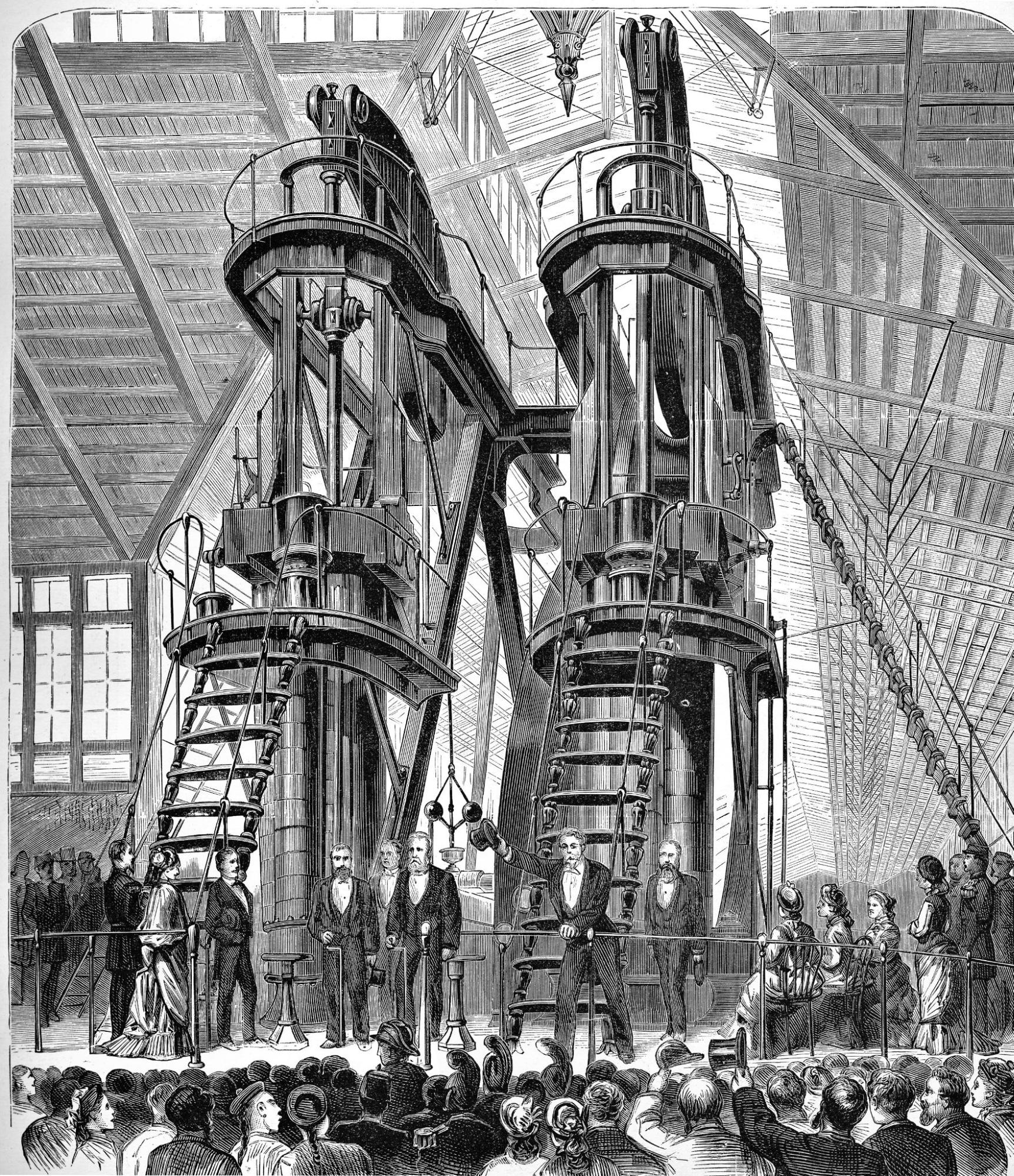

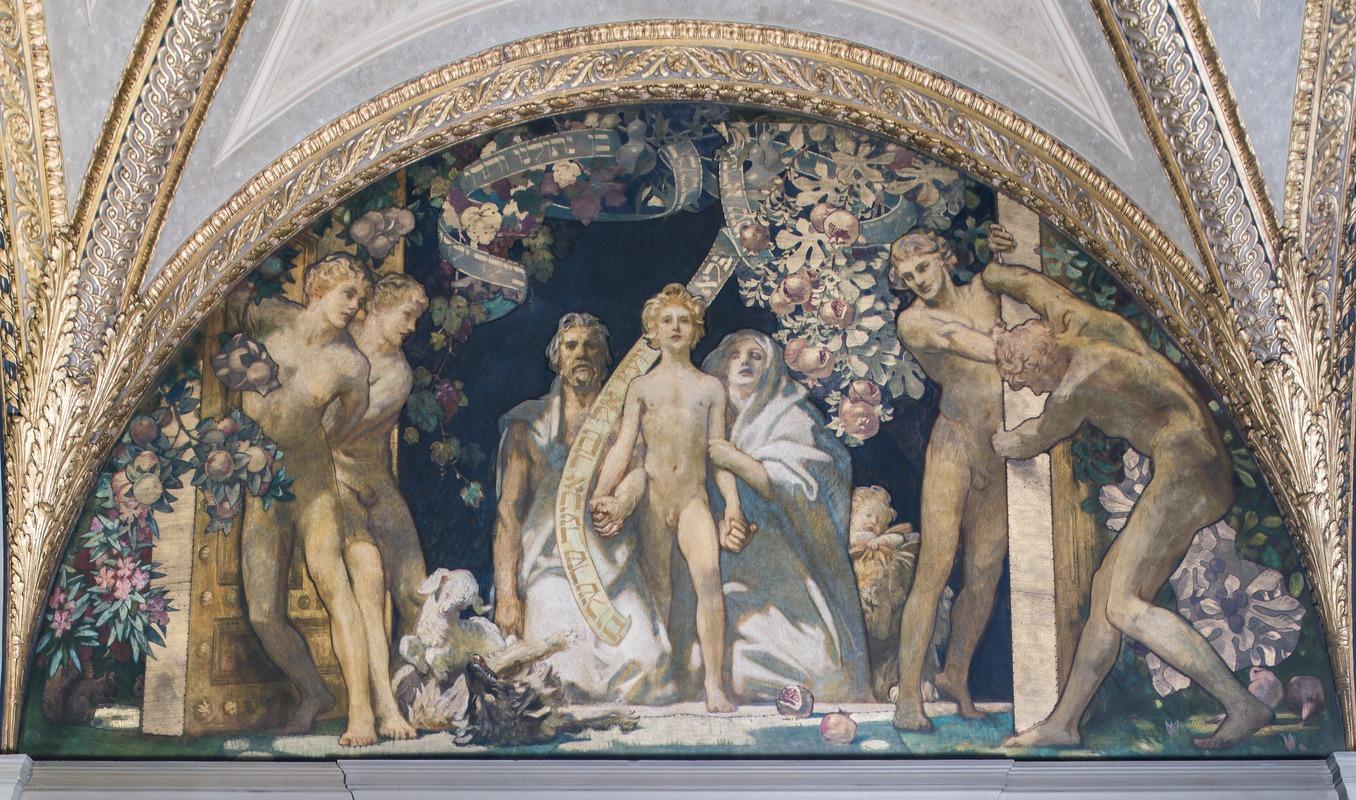

John La Farge

Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still

-

Thomas Cole

The Tempter

-

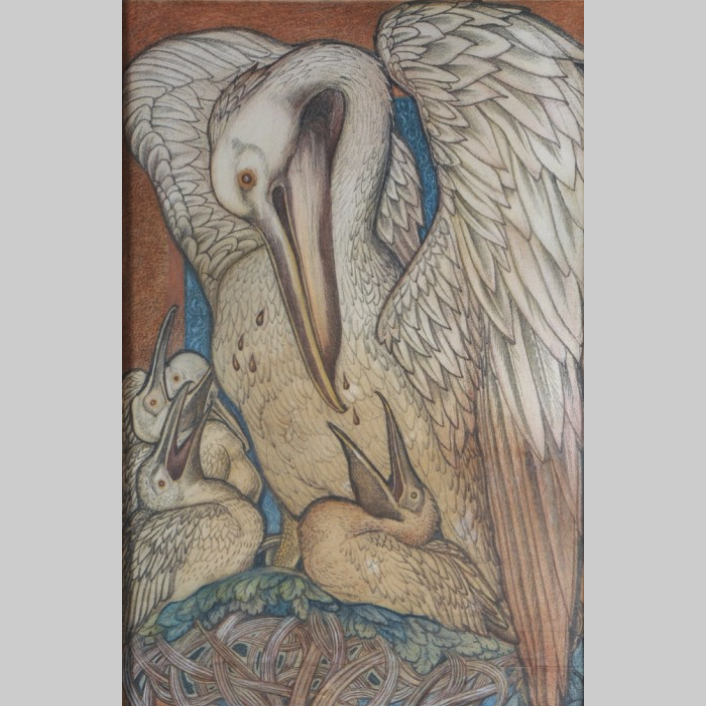

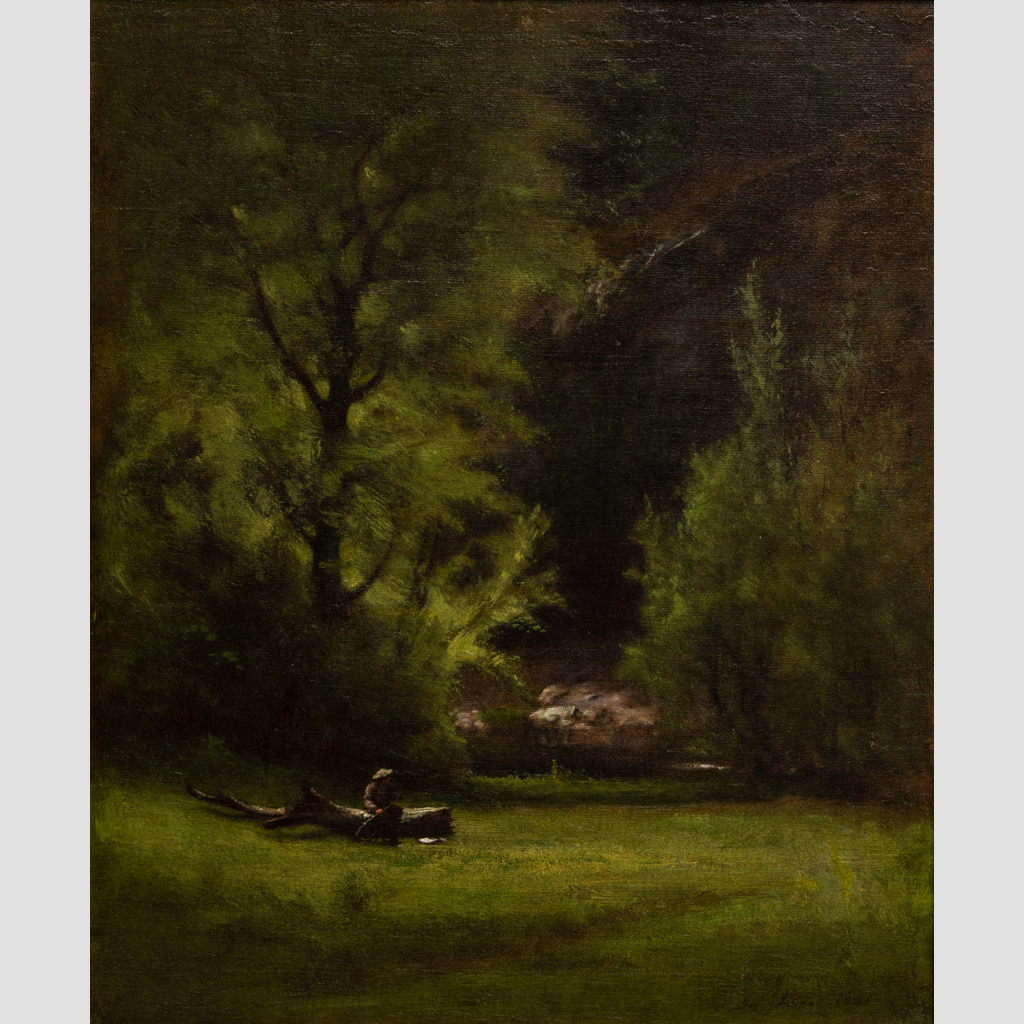

John La Farge

Wood Interior

-

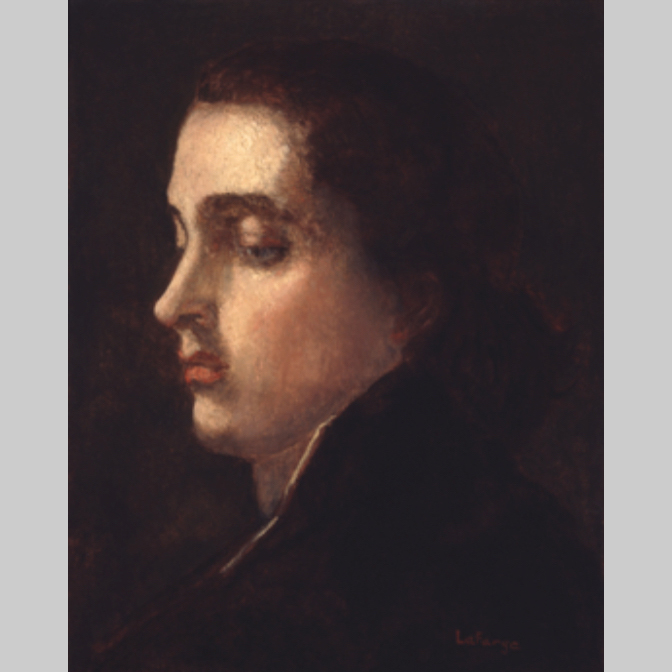

John La Farge

Portrait of Margaret Mason Perry La Farge

-

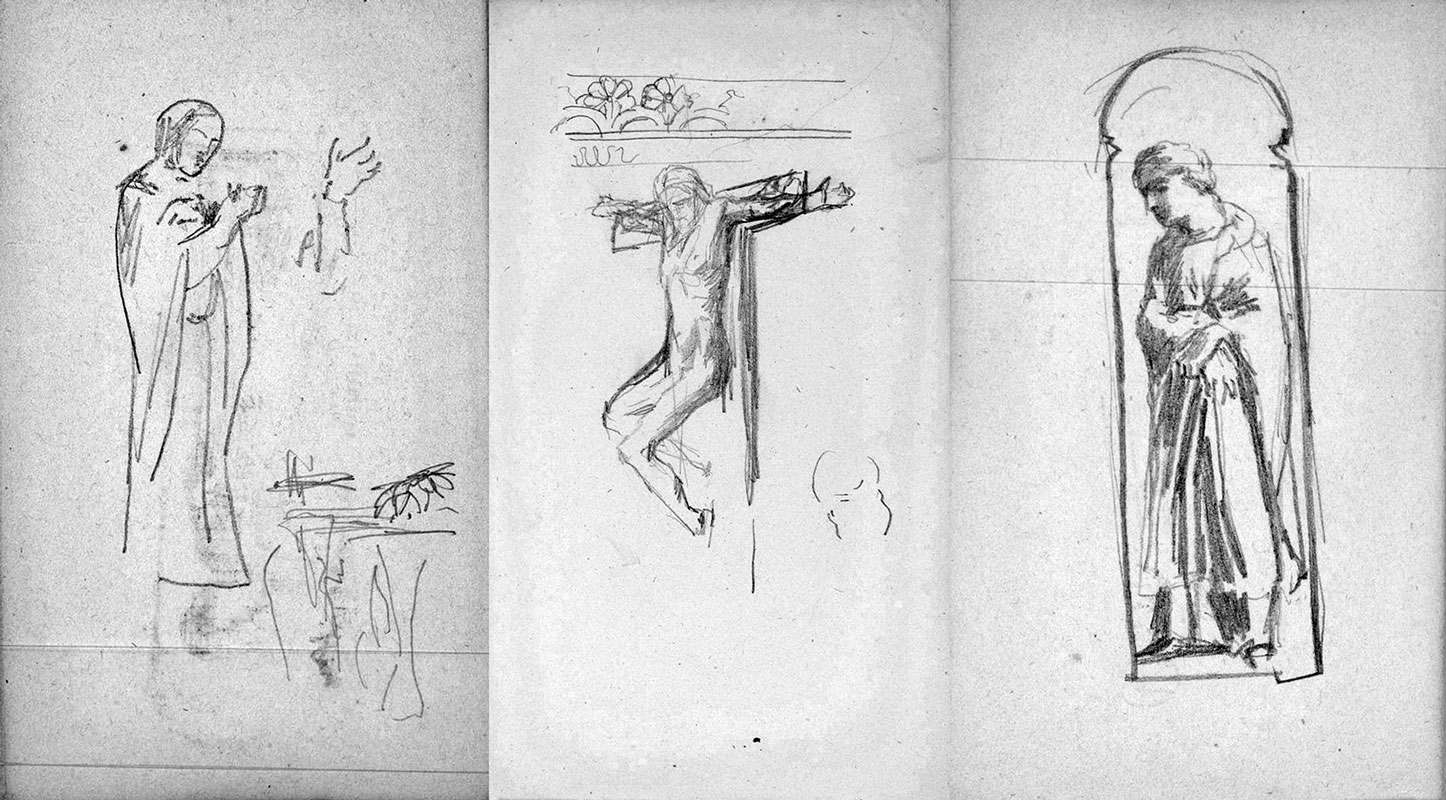

John La Farge

St. John the Evangelist at the Foot of the Cross

-

John La Farge

The Virgin at the Foot of the Cross

-

John La Farge

Evening Study, Newport, Rhode Island

-

John Frederick Kensett

A View of Niagara Falls

-

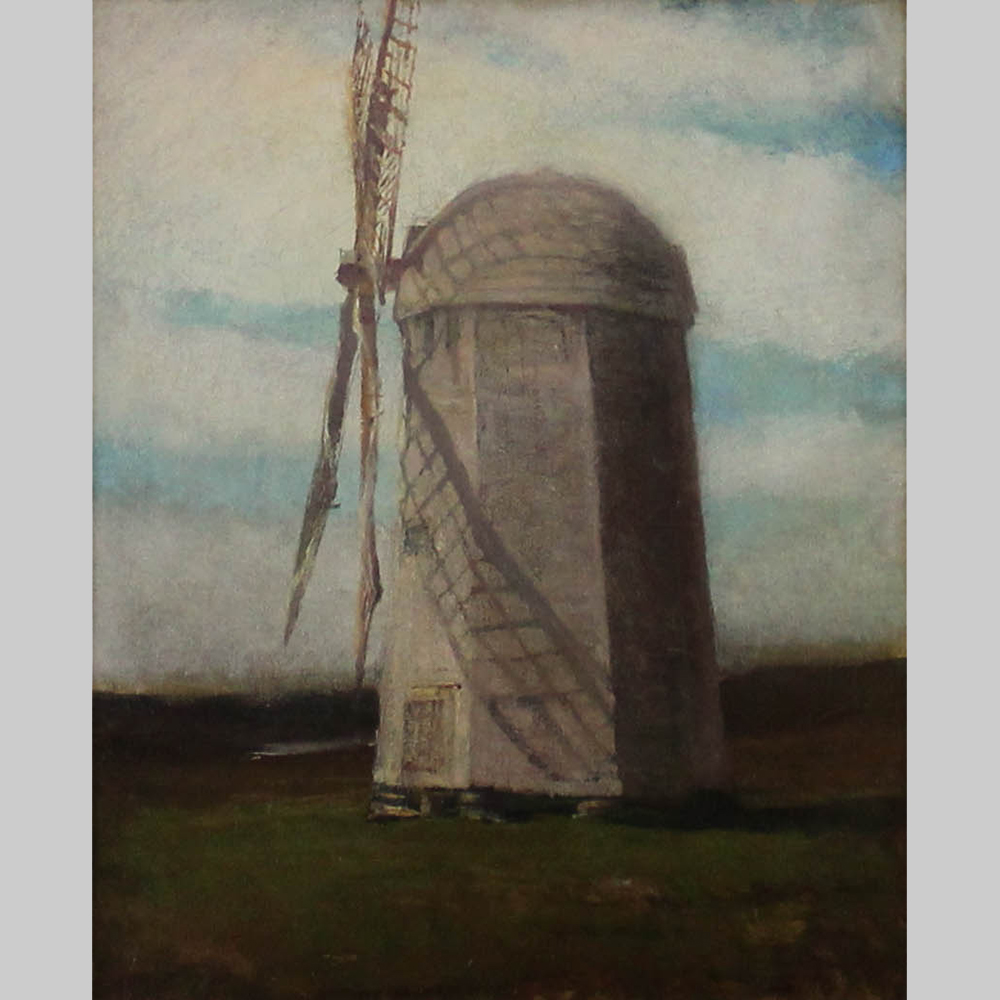

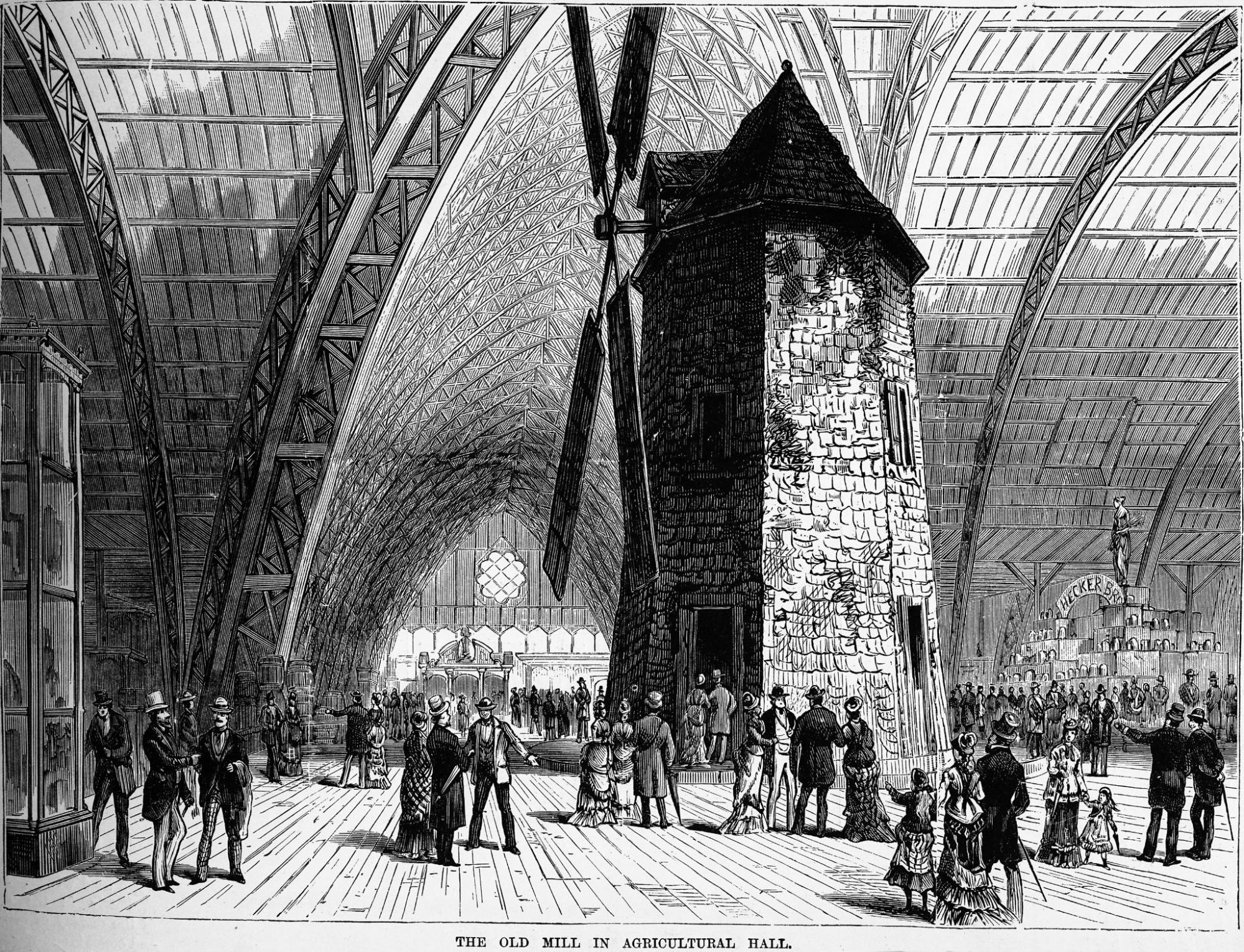

John La Farge

Windmill (Newport, Windmill, near Easton’s Pond. Early Spring, Southeast Wind)

- Sitar Family Conference Room (Room 105)

-

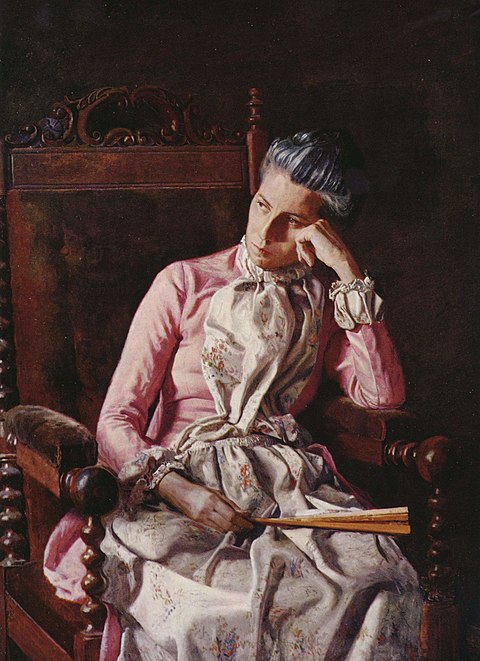

George Bellows

Old Lady with Blue Book

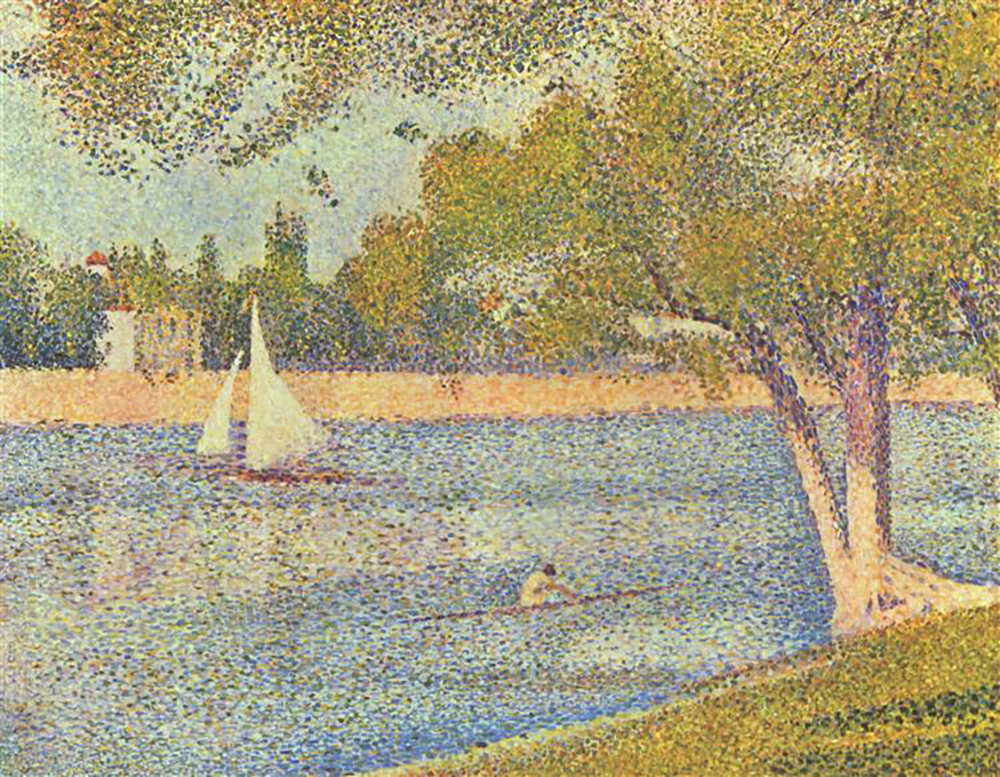

William James Glackens

Sailing Boats, Paris

-

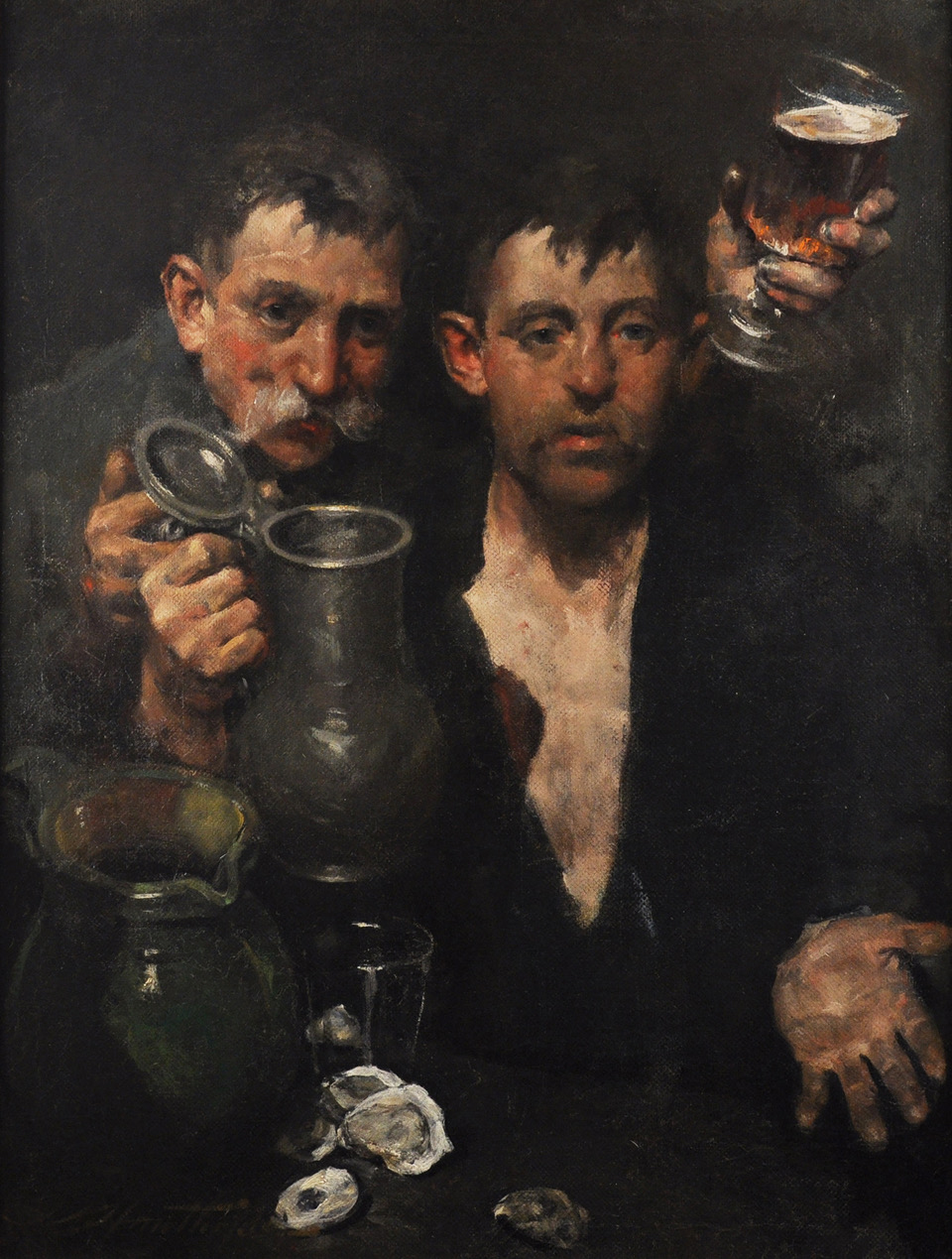

Charles Webster Hawthorne

The Oyster Eaters

-

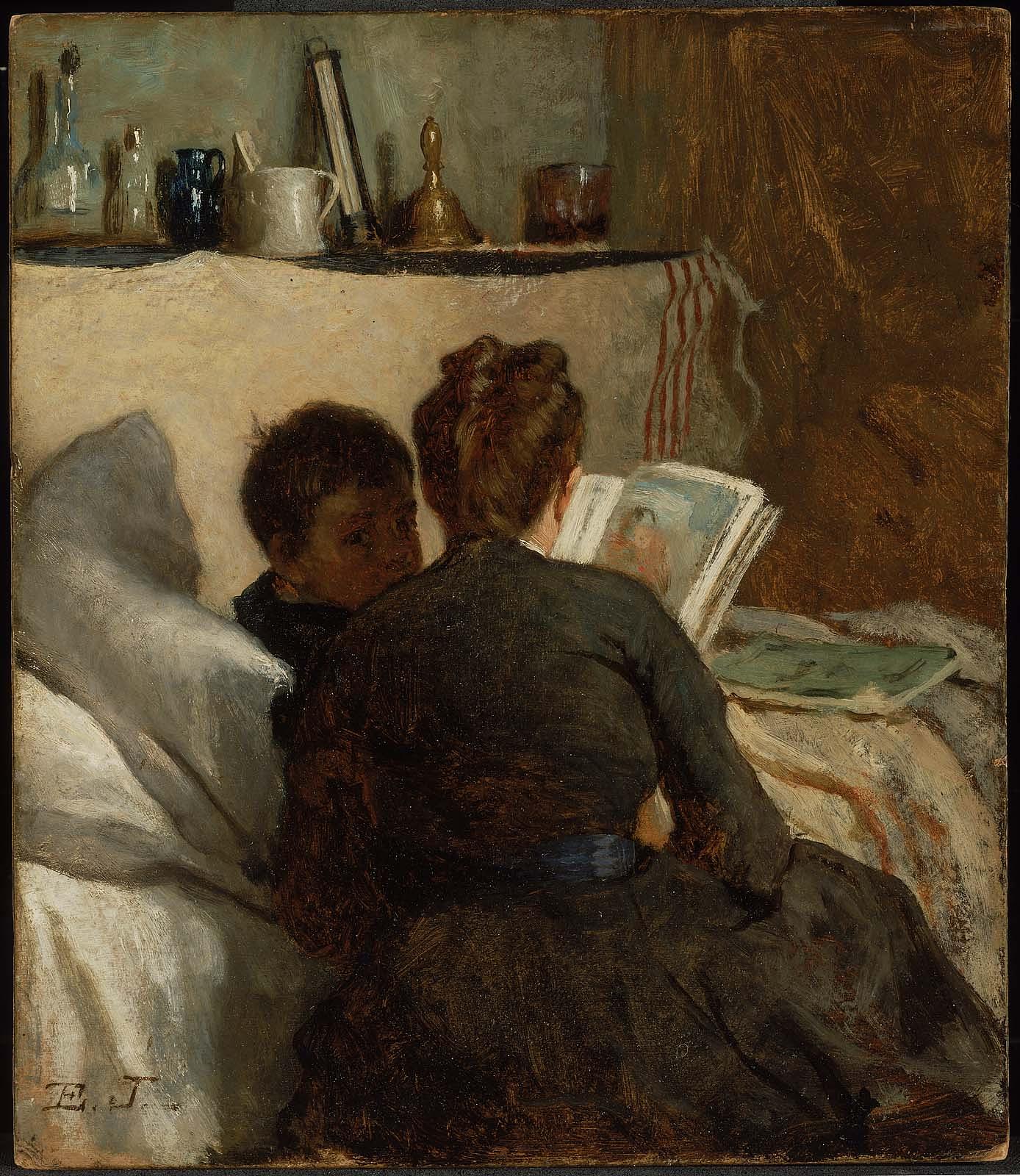

Eastman Johnson

Mother and Child: The Reading Lesson

-

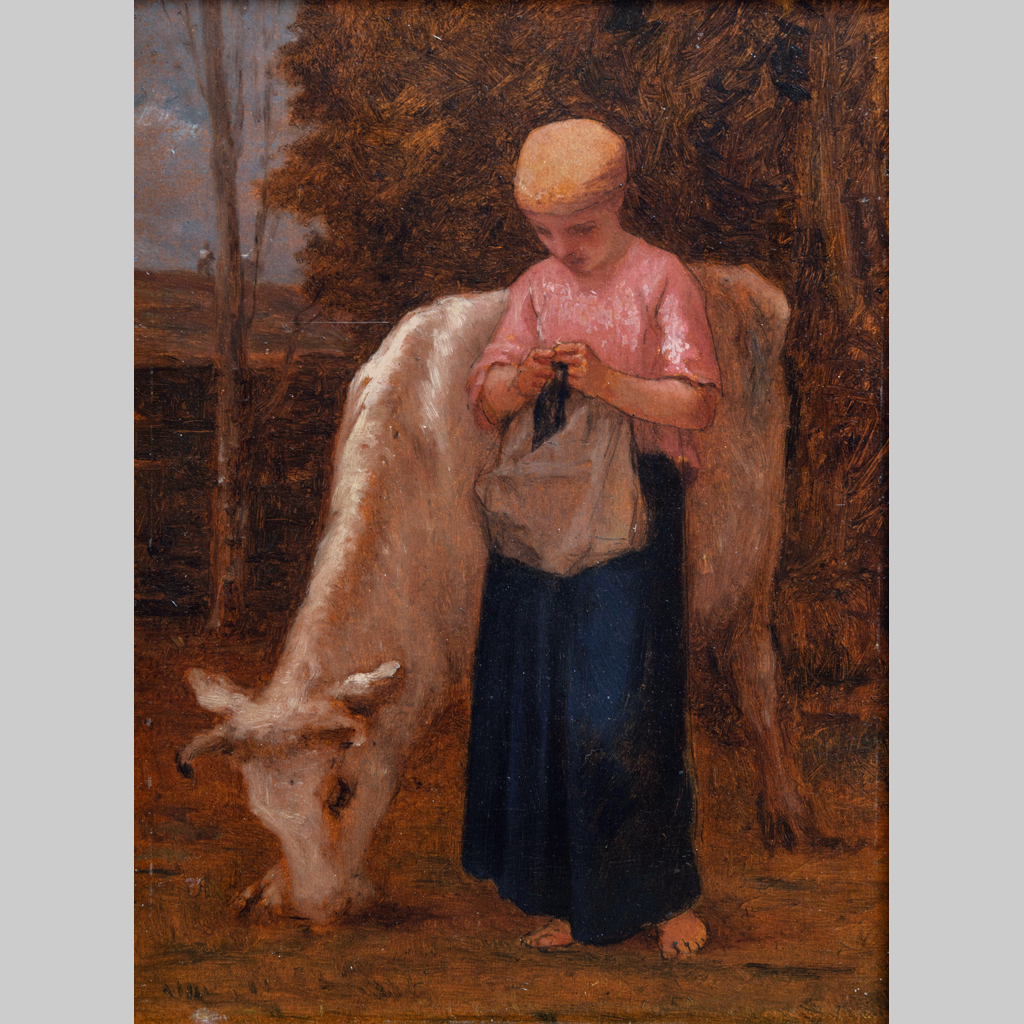

William Morris Hunt

Woman Knitting and Cow (Fontainebleau)

-

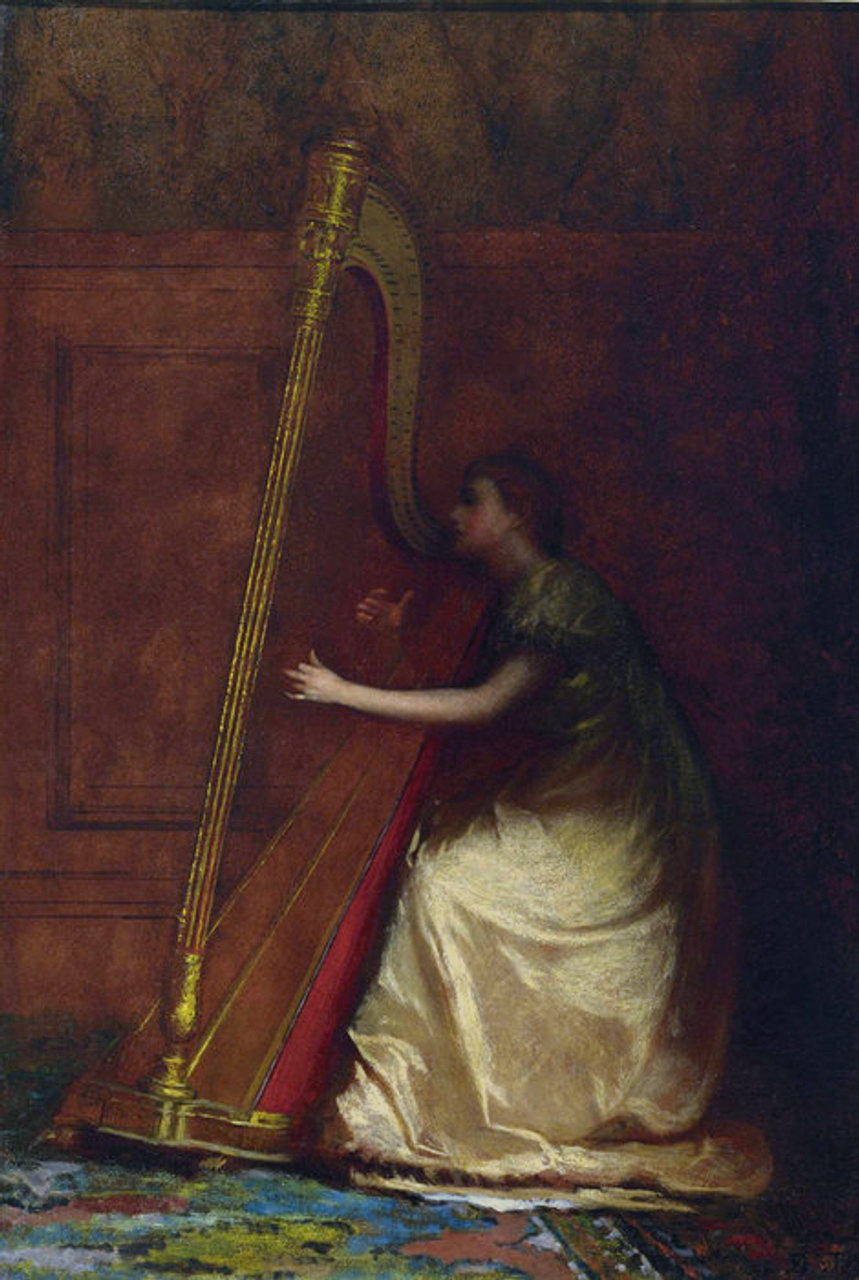

Eastman Johnson

Woman Playing a Harp

-

Edward Coley Burne-Jones

The Annunciation

- Room 107

-

Fitz Henry Lane

View of Gloucester Harbor

-

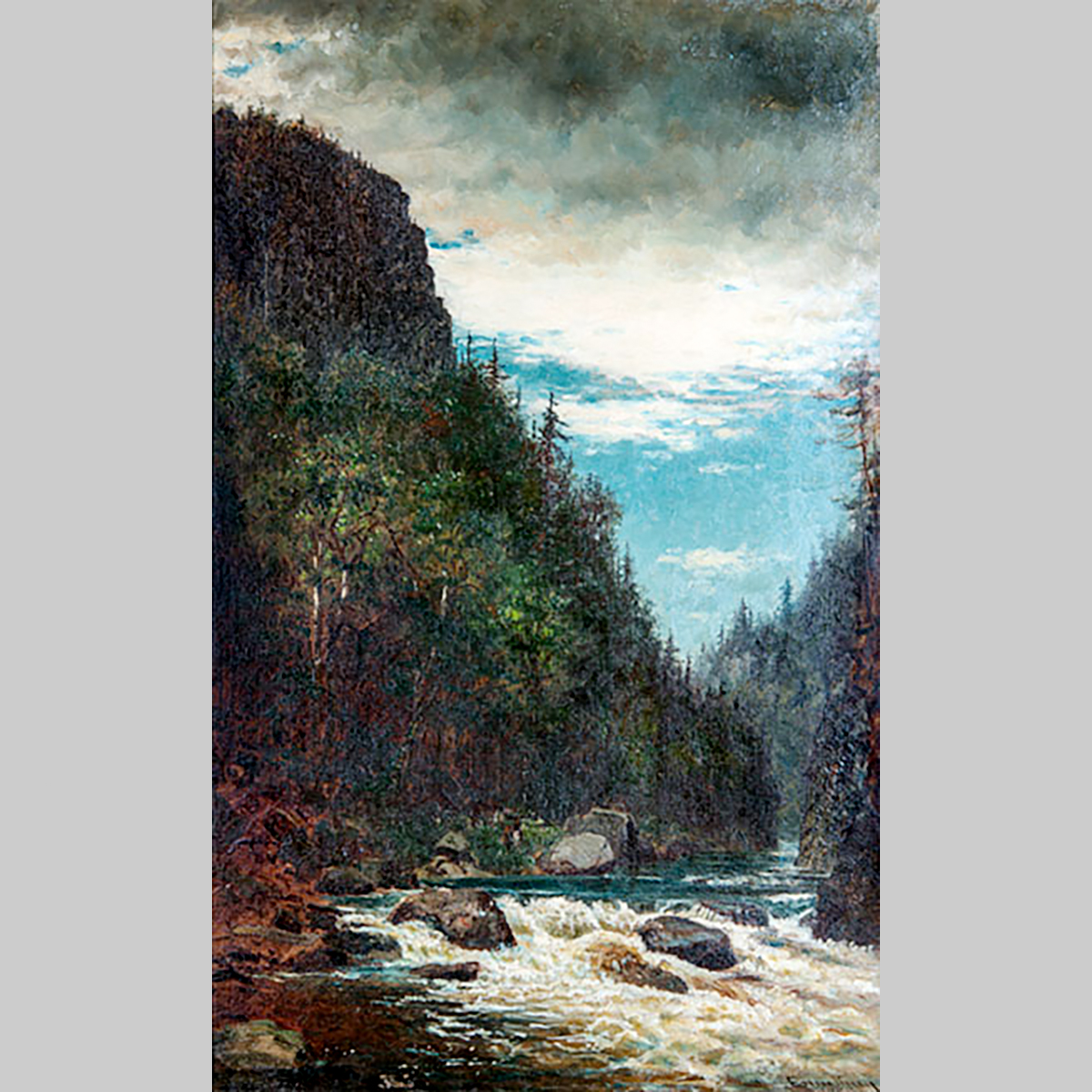

Jack Butler Yeats

Rushing Waters

-

Jack Butler Yeats

Quiet Men

-

Jack Butler Yeats

Farewell to Mayo

-

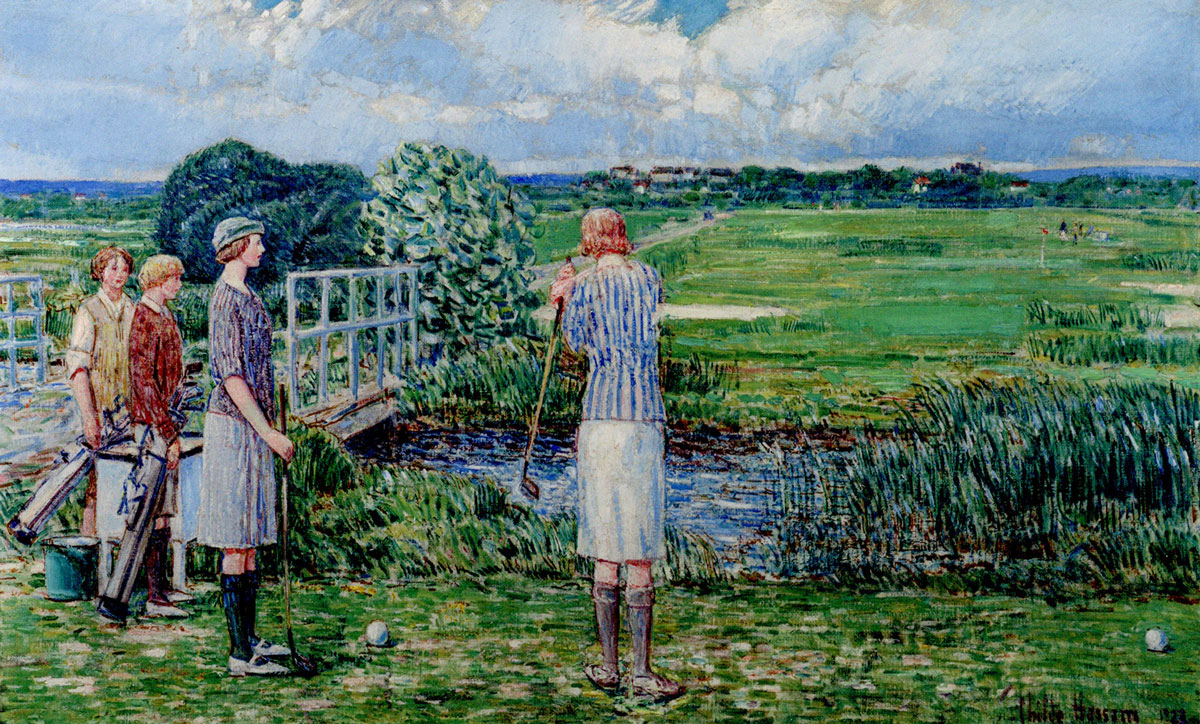

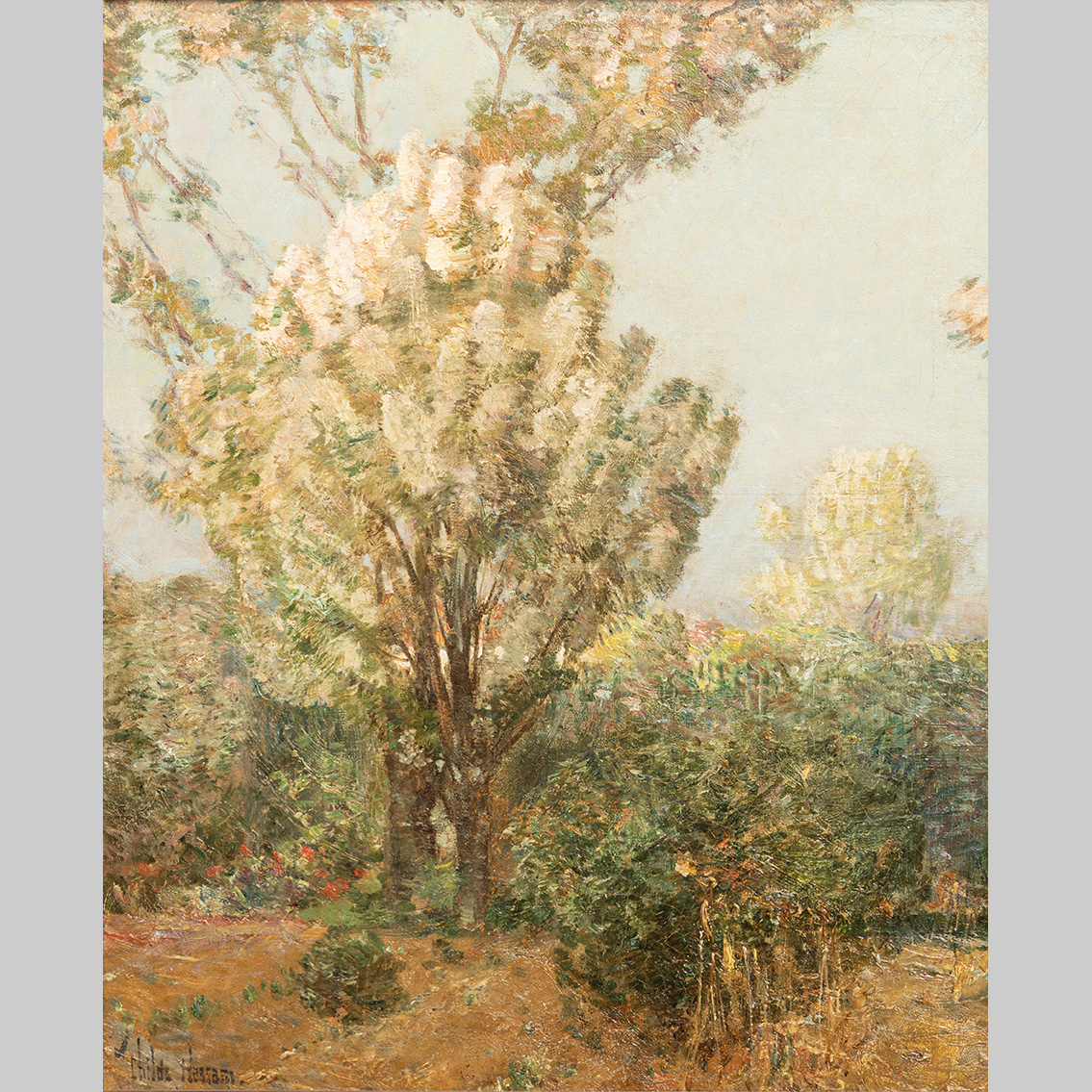

Frederick Childe Hassam

Water Hazard—Maidstone Links

-

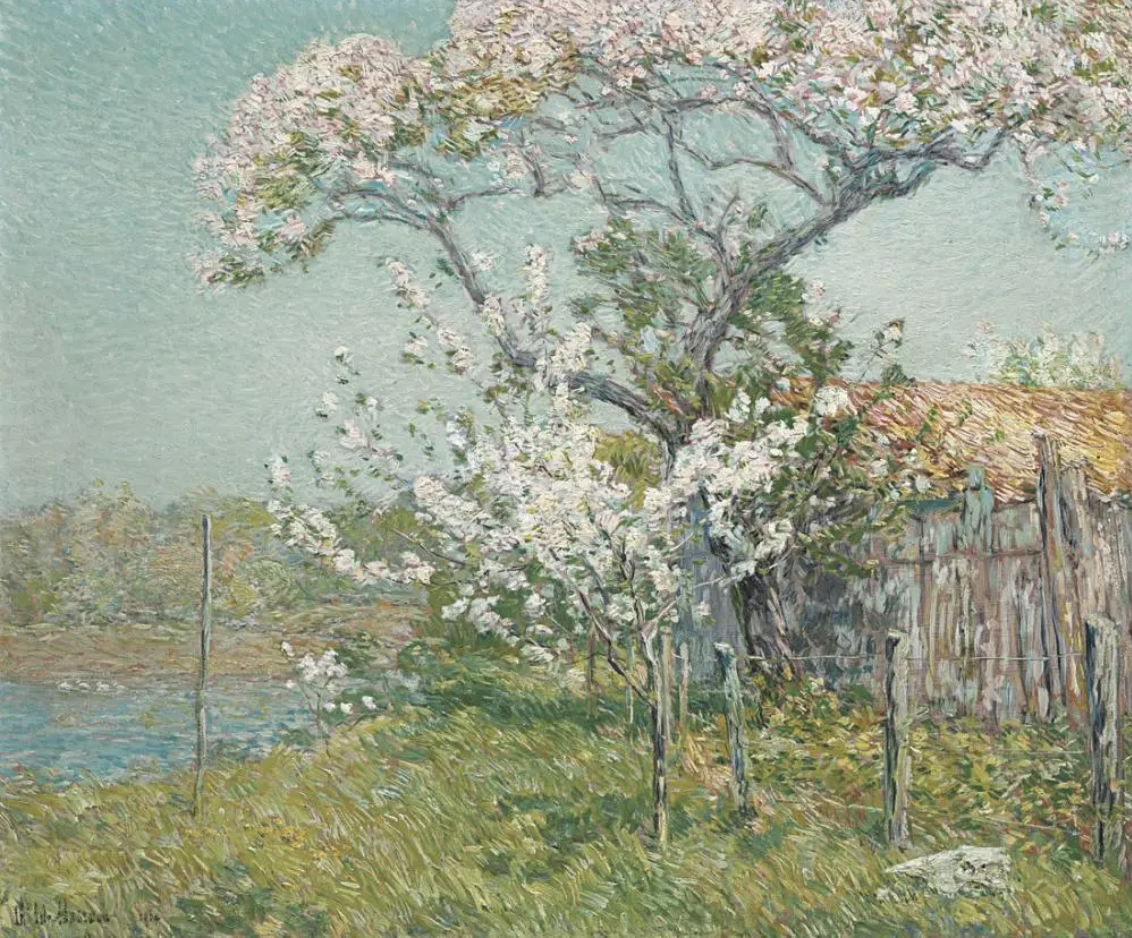

Frederick Childe Hassam

Spring Flowering Trees

-

Robert Salmon

View of Boston Harbor, Ship Going Out

-

Martin Johnson Heade

Orchid and Hummingbirds near a Mountain Lake

-

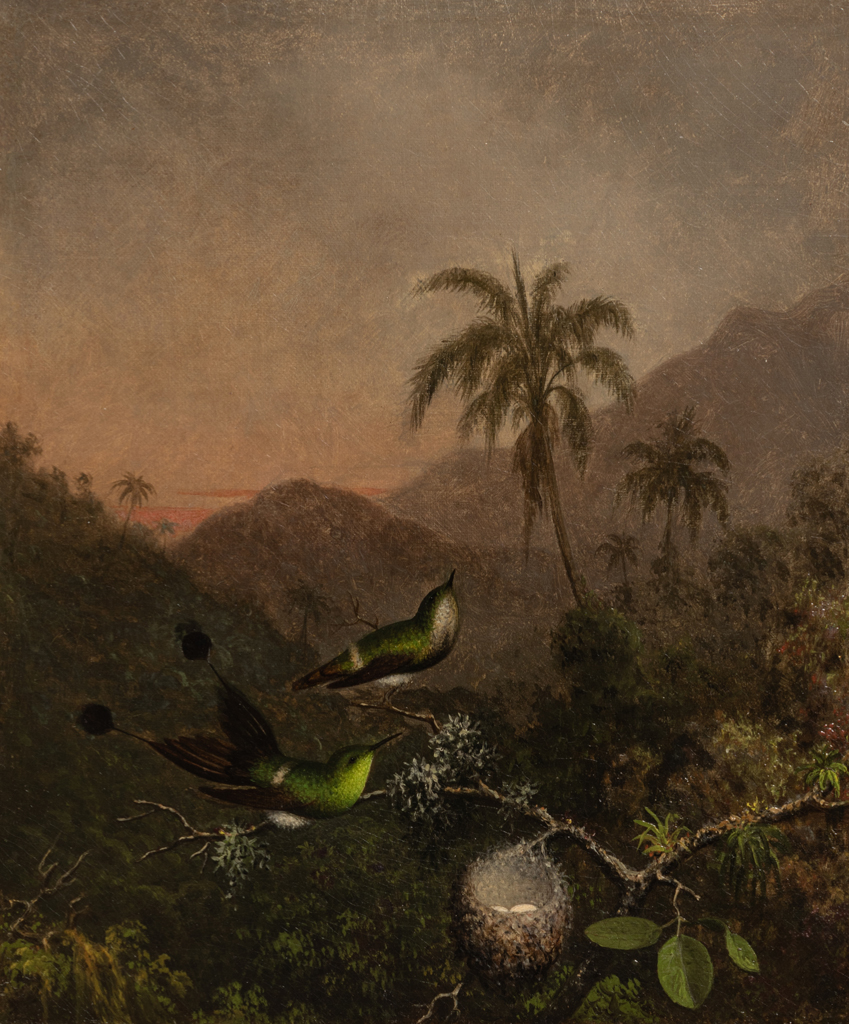

Martin Johnson Heade

Two Green-Breasted Hummingbirds

-

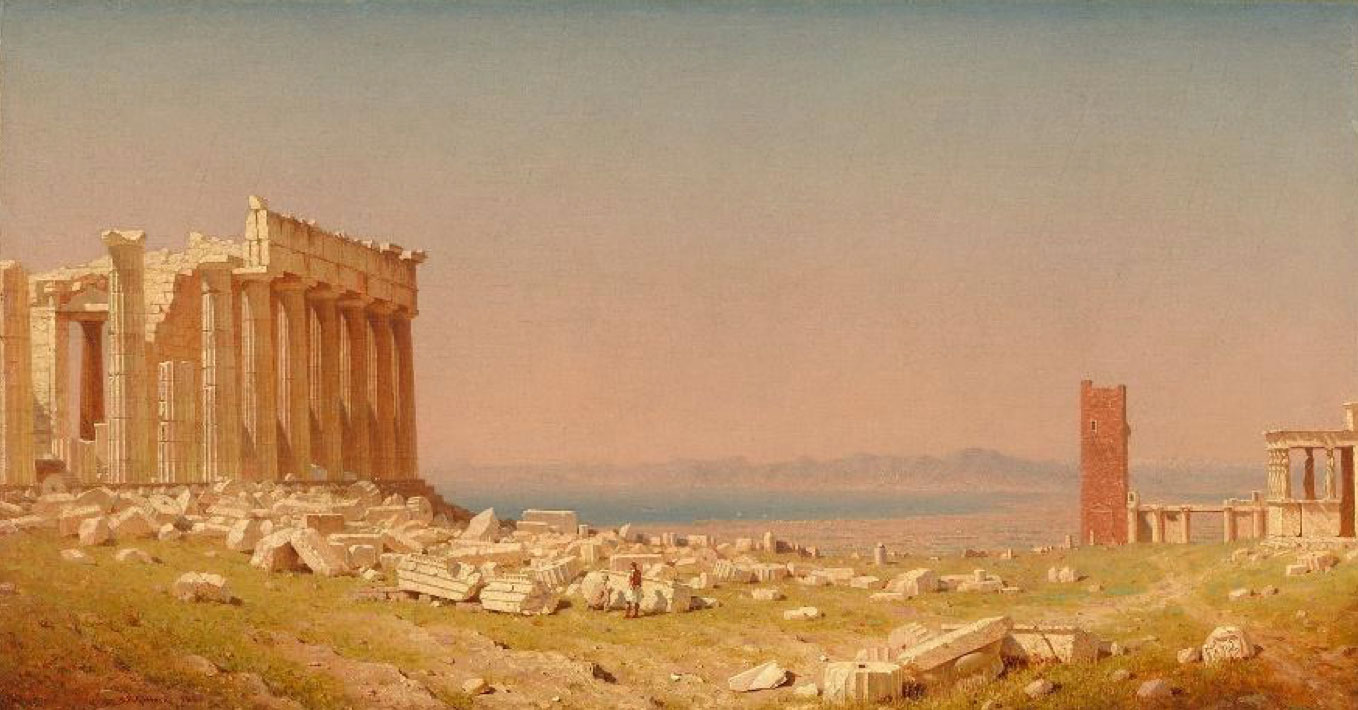

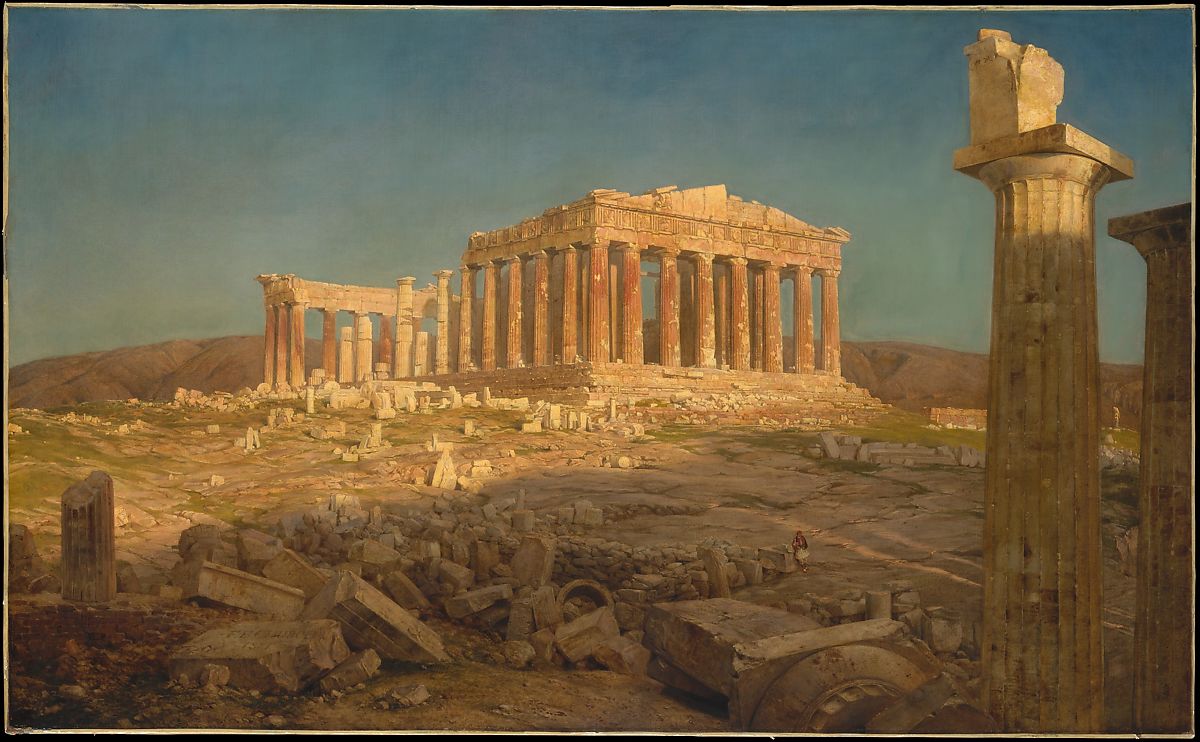

Sanford Robinson Gifford

The Ruins of the Parthenon

-

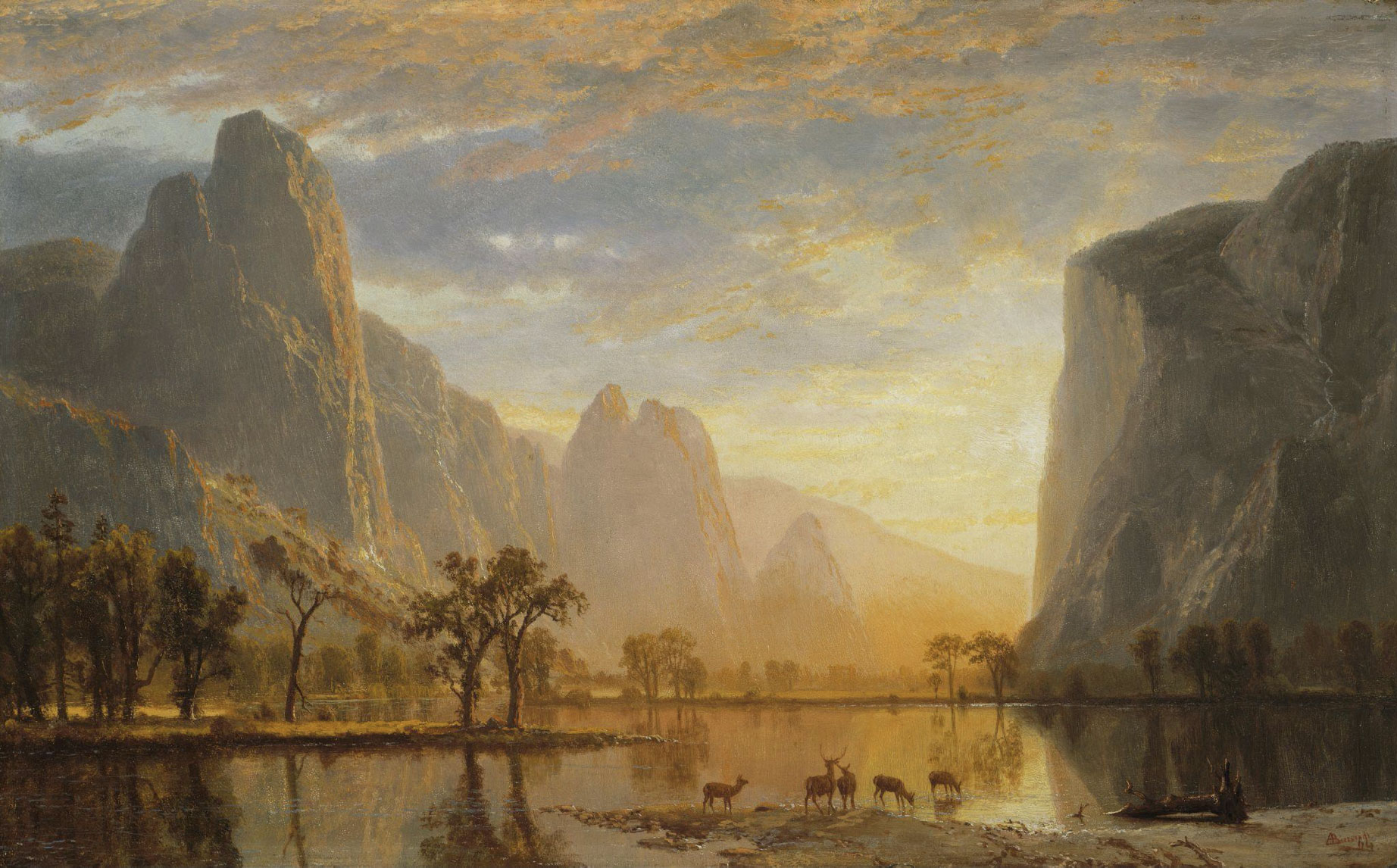

Albert Bierstadt

Owens Valley, California

Albert Bierstadt

Near the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains

-

Fitz Henry Lane

Sunset after a Storm

- Sister Caroline Putnam Room (Room 109)

-

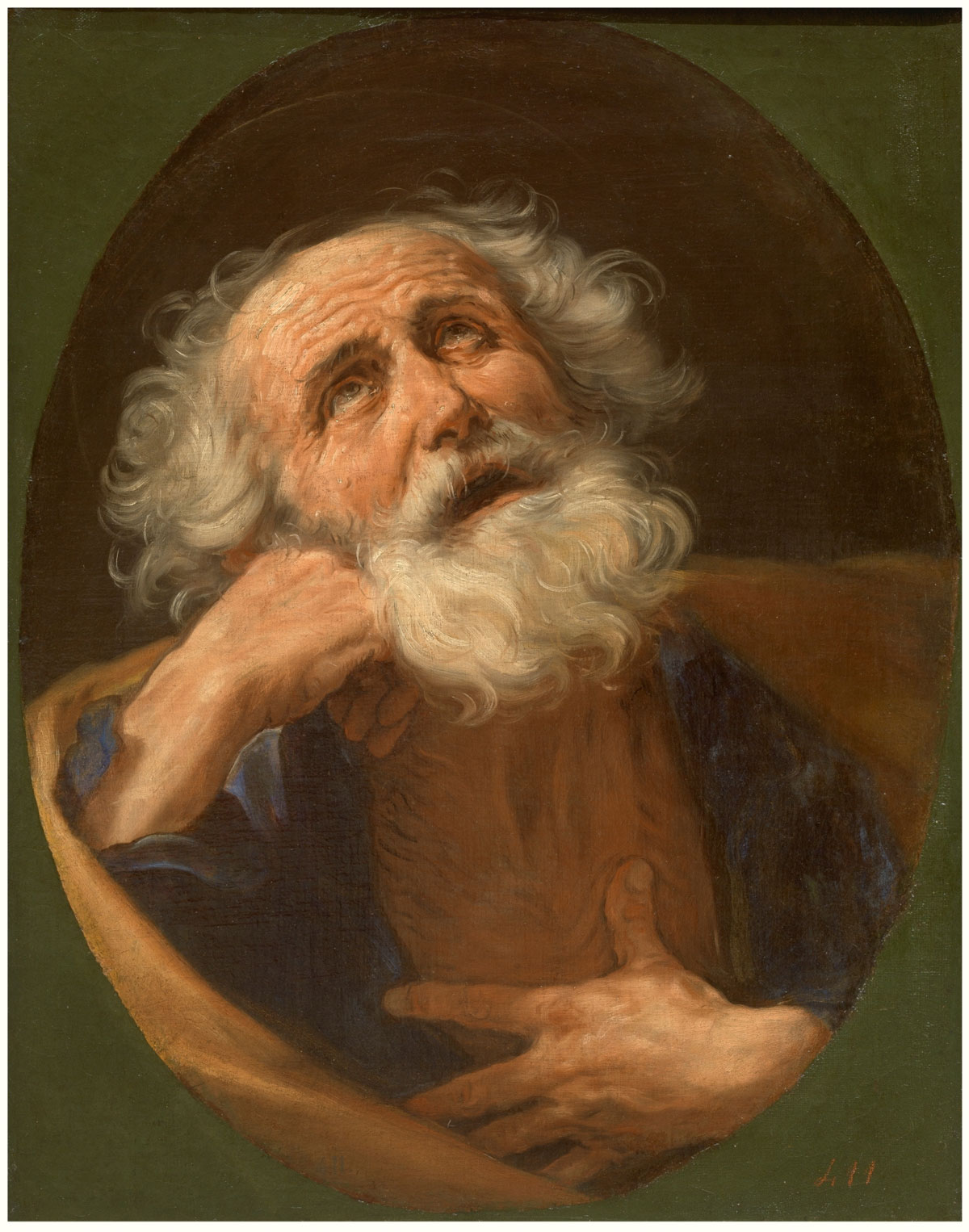

Marco Benefial

Stoning of St. Stephen

-

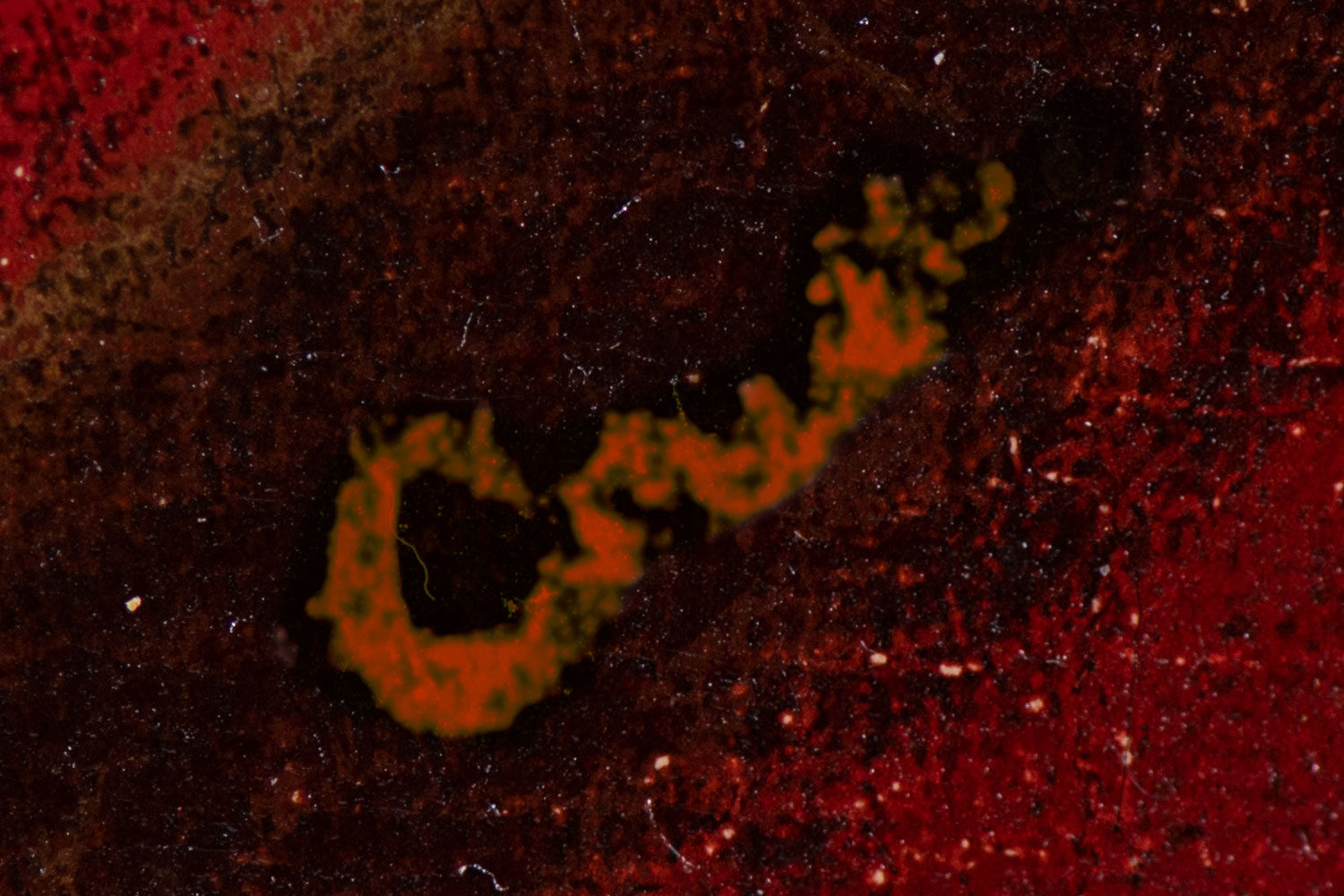

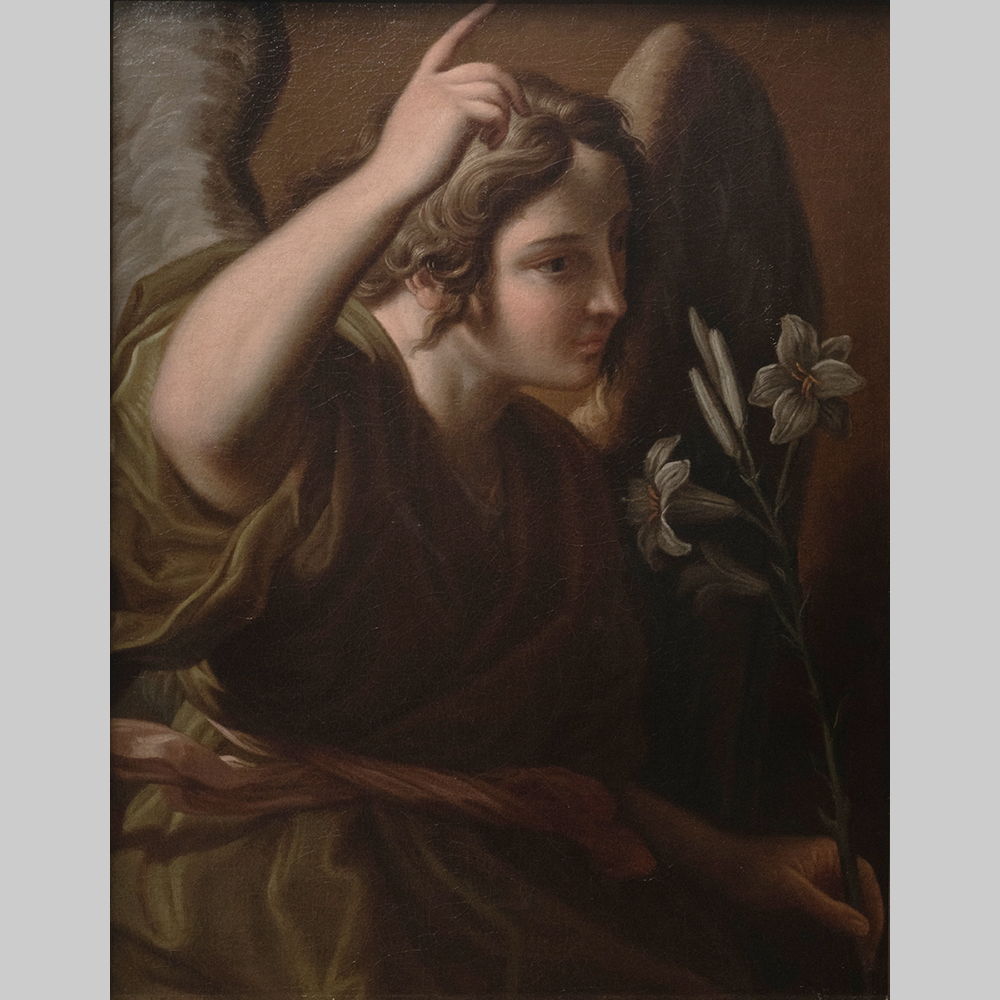

Gaetano Lapis

Angel of the Annunciation

-

Unknown artist (Emilian school)

Holy Family with St. John

-

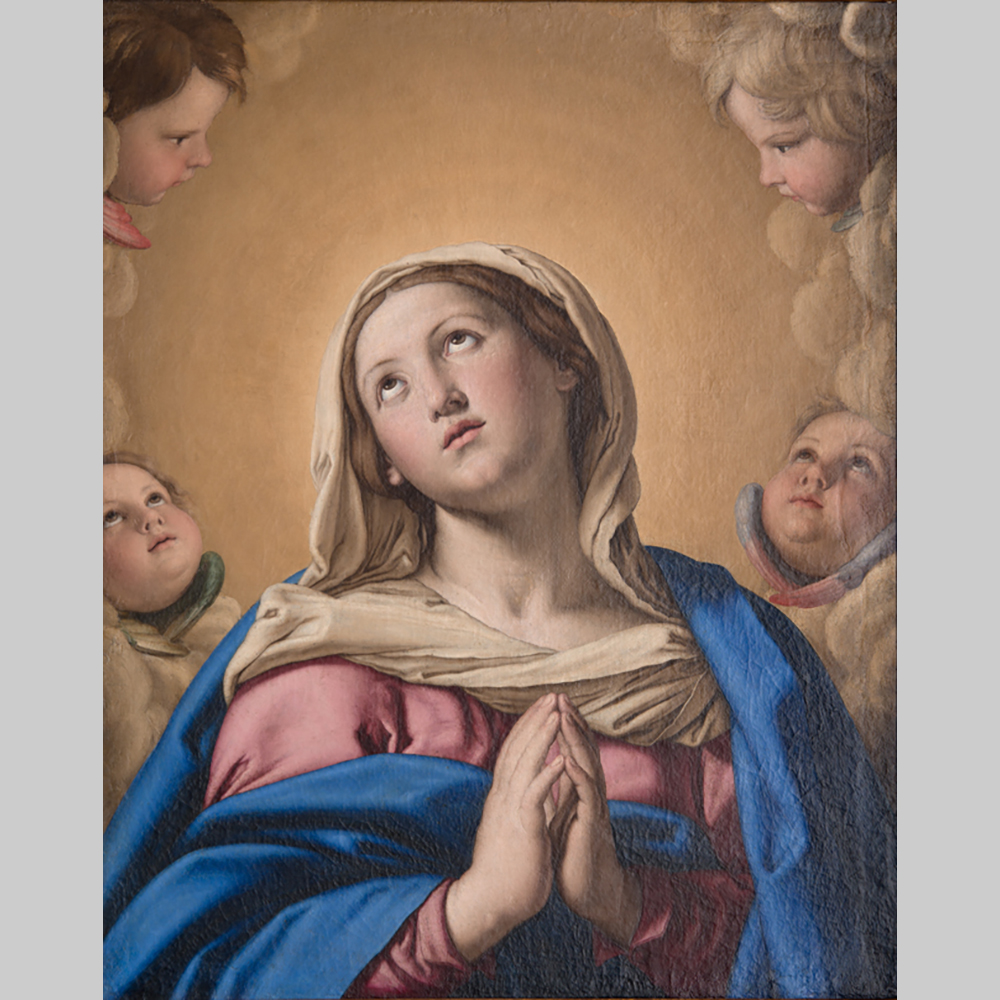

Giovanni Battista Salvi (Sassoferrato)

Madonna of the Cherubs

-

Pierre Subleyras

Meal at the House of Simon the Pharisee

-

Giambettino or Giuseppe (Fra Felice) Cignaroli

Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist

-

Michele Tosini and assistants

Madonna with Christ and St. John the Baptist

-

Orazio de Ferrari

Woman Taken in Adultery

- Hill Family Conference Room (Room 111)

-

William Lamb Picknell

Le déclin du jour (Fort Carré, Antibes, France)

-

William Merritt Chase

Autumn Still Life

-

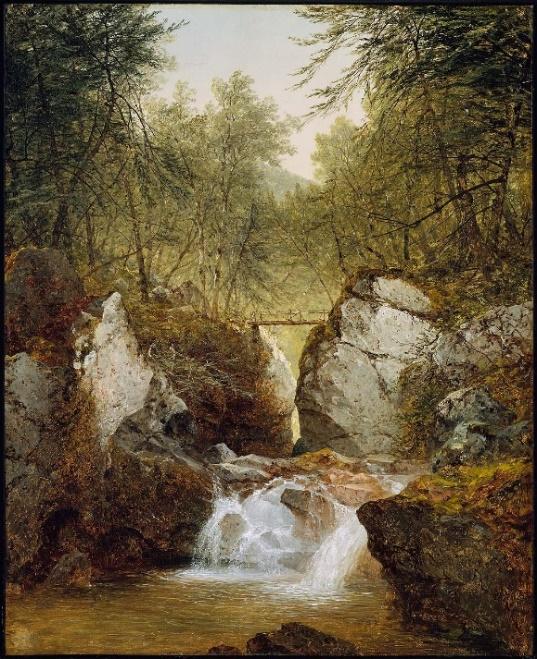

John Joseph Enneking

Mountain Stream

-

Elihu Vedder

Peasant Girl Spinning (Spinning under the Olives)

-

Harriet Cany Peale

Idealized Portrait of a Woman (Female in a Turban)

-

After Annibale Carracci

Holy Family (Montalto Madonna)

-

William Trost Richards

Tintagel

-

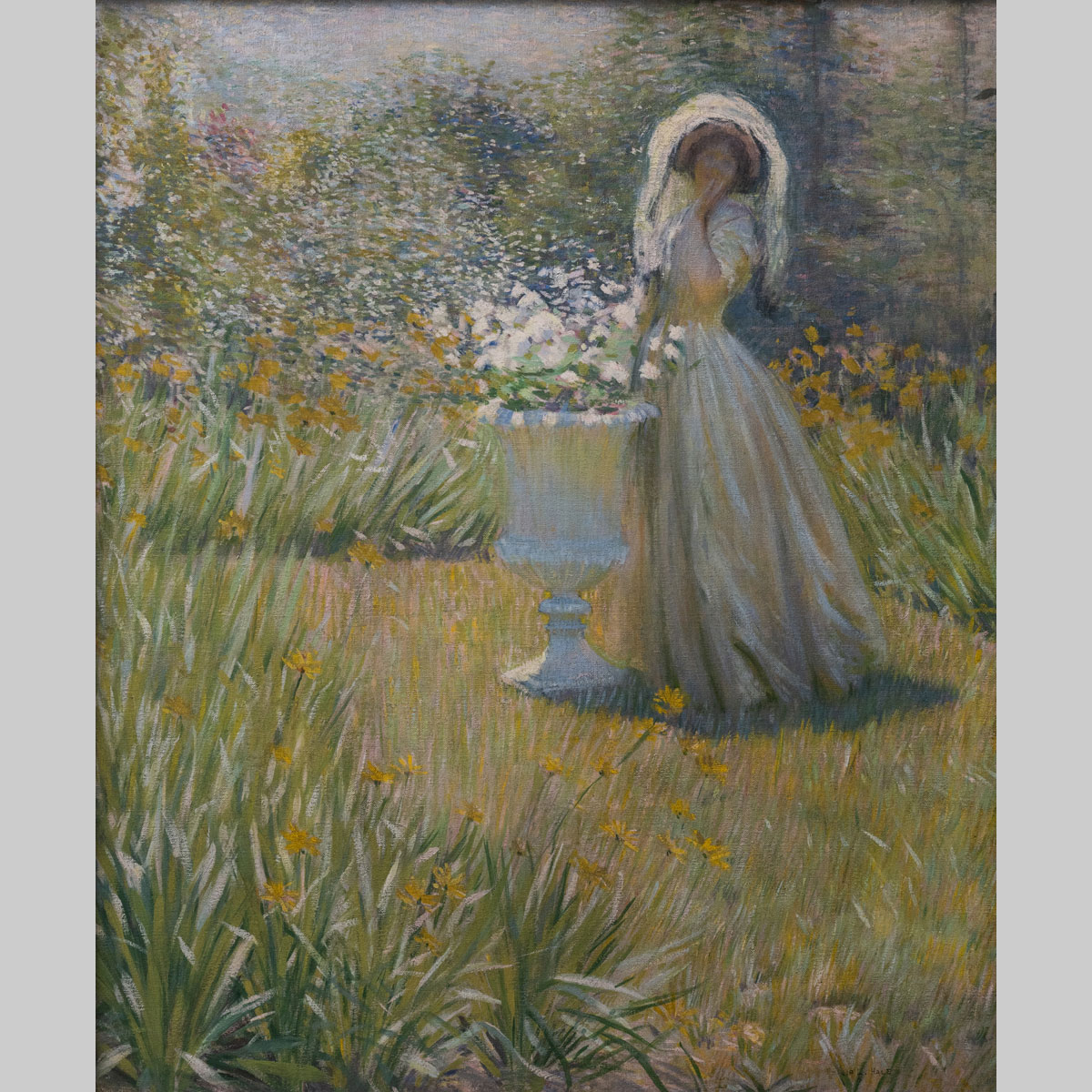

Philip Leslie Hale

In the Garden

-

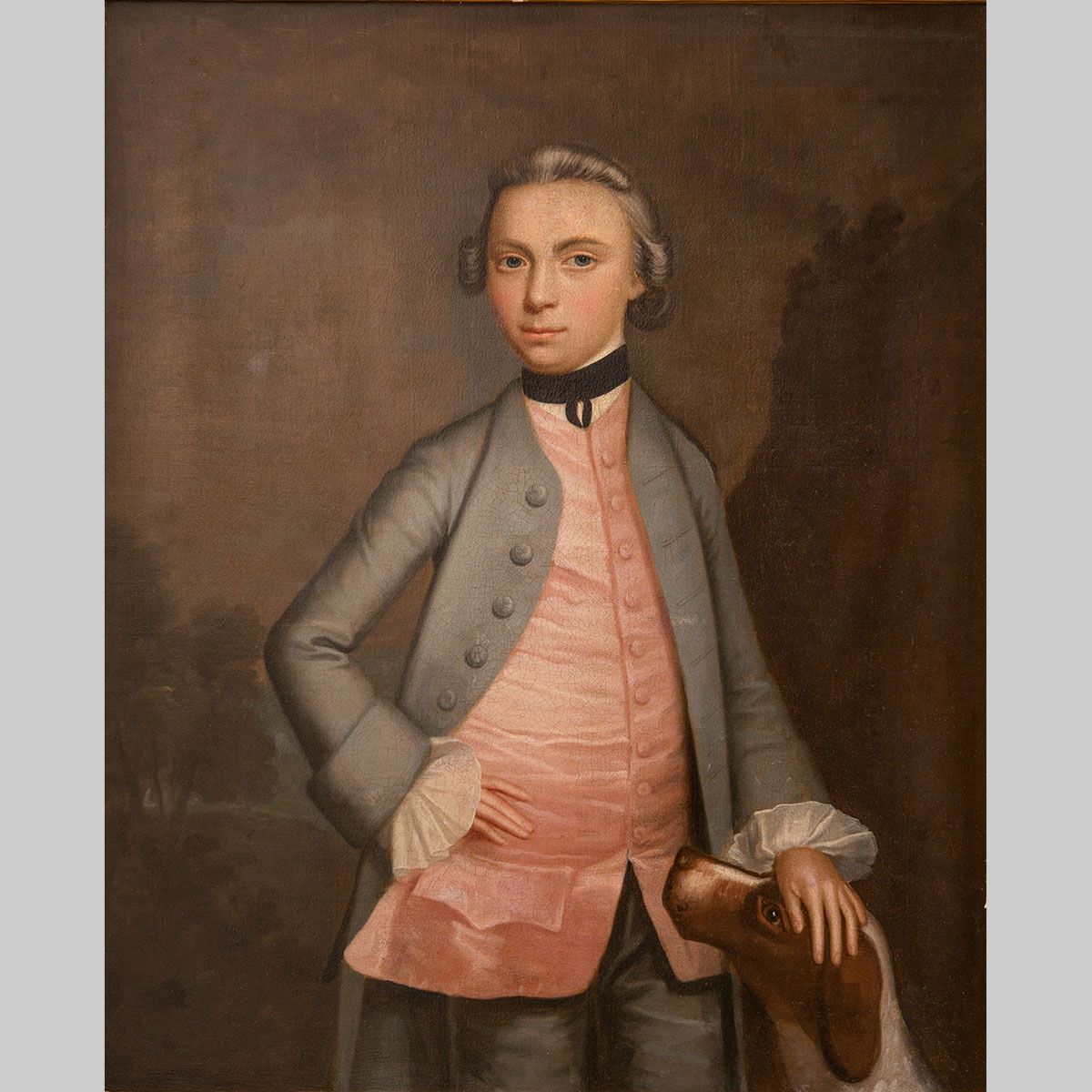

John Wollaston

Portrait of a Boy

-

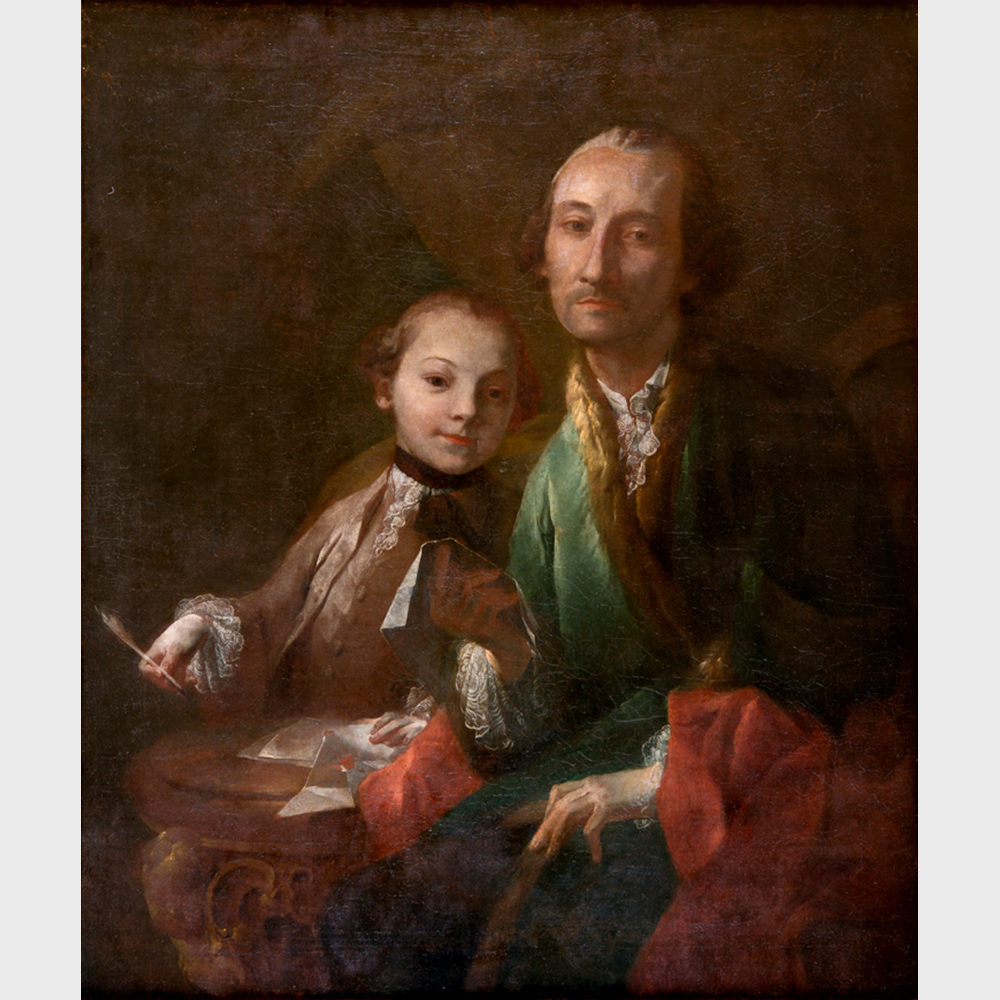

Alessandro Longhi

Portrait of Venetian Man and Boy

-

Anthonij (Anton) Mauve

Snow Scene with Sheep

-

Jules Dupre

Landscape with Woman in Red

Jeffery Howe

Professor Emeritus, Art History