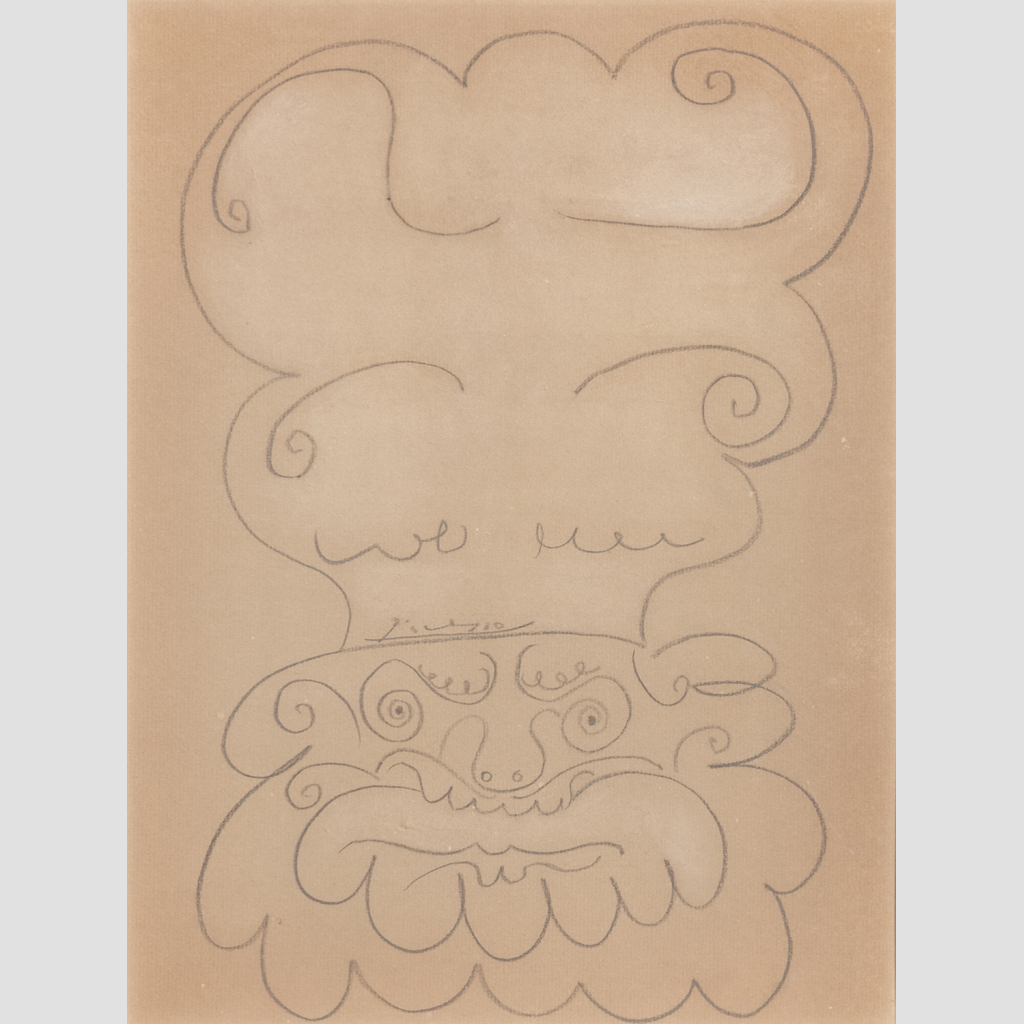

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

L’homme barbu (Bearded Man), n.d.

Pencil and white pigment on paper

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.59

Kevin Lotery

Assistant Professor, Art History

Not much is known about Pablo Picasso’s undated little pencil drawing. It ostensibly depicts a bearded, wild-eyed man in harsh frontal view, his gaze locked on us, his spectators. Lacking any modeling, the face is flattened against the sheet, its beard delineated by a looping and arching contour line that also bounds the great hat above. Lightly highlighted with white pigment of some kind, this absurd headdress may represent a chef’s toque, though its morphology—and its ambiguous relation to the mesmeric face below—remains open to the viewer’s interpretation. The comical, even grotesque caricature possesses no neck that might connect it to a body outside of the frame; it is, instead, a being wholly a product of the page itself, which tightly bounds both head and hat a single, autonomous unit. The physiognomy is constructed by a carefully choreographed collection of calligraphic spirals and decorative arabesques, which unfold like handwriting across the sheet.

Indeed, the artist not-so-subtly disguises his signature amongst these so that it operates both as the authorial mark of the master and as a mere ornamental detail. Denied pride of place, it is endowed with no more or less privilege than any of the other glyph-like fragments surrounding it. Like individual phonemes in the artist’s visual language, they are all allowed to exist both as individual calligraphic units, but also as elements within the larger whole of the head and hat. We see, in other words, how a spiral might come to signify “eye” only by virtue of its relationship to neighboring curlicues (“eyebrows”) or the central U-shape (“nose”).

At the same time, these individual units are free, in part, to perform other anatomical formations, erotically sliding between individual bodily fragments and complete face. While we might search for a specific subject here (whether man, minotaur, or mad hatter), we would be better served by locking our eyes on the hypnotic gaze, letting our vision be caught in the endlessly spiraling madness of signification itself.

Eileen Sweeney

Professor, Philosophy

Pablo Picasso’s L’homme barbu forces the viewer to smile both at the humor of its exaggerated headpiece (a chef’s toque?), hair, and beard, but also at the virtuosity of the simple drawing. Many lines are long and unbroken; others are short squiggles that magically convey so much—not just shape but also mood and feeling. Single lines create the beard, hair, eyes, eyebrows, and hat, versus the mismatched squiggles on the hat and around the eyes and nose. Here Picasso displays his autonomy as artist, his engagement in pure play in his creation of a character out of whole cloth. Here less is emphatically more, illustrating the power of abstraction to make something more real, leaving out all but the barest line. This Picasso drawing, unlike his cubist paintings and collages, does not convey multiple sides and dimensions on a flat surface. Rather, with only a few lines, Picasso suggests a chef with lion-like beard and hair, palpable and alive even though transparent.

“Modern” art and modernism put an emphasis on the autonomy of art and the artist’s freedom from tradition and cultural norms. The modern artist rejects traditional artistic conventions, like realism and perspective, as well as cultural, especially bourgeois, expectations around, for example, class and sexuality as well as beauty. The motto of modern art, “art for art’s sake” asserts that art does not serve religion or morality; it aims to replace and displace both; art is only about itself and the artist is answerable only to himself. If we think about Kant’s view of the tremendous power of the mind to effectively “construct” reality, to synthesize and organize the blooming buzzing onslaught of sense data, we can see in the artist the figure to de-construct and create a new reality—Picasso once described his pictures as “a sum of destructions.” Thus, perhaps no other artist embodies that power more paradigmatically than Picasso, exhibiting endless creativity, breaking multiple times even with his own style, playing with reality in new ways. For the German philosopher Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805), following Kant, “play” or the play drive, is our most human activity; play mediates between the mind which transcends time and space, and the empirical, sensible self, immersed in matter. Picasso’s freedom to create transcends the material world and even his own art, but his sensuality places him firmly in the realm of flesh and blood.