Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–80)

The Ruins of the Parthenon, 1869–80

Oil on canvas

McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.49

Jeffery Howe

Professor Emeritus, Art History

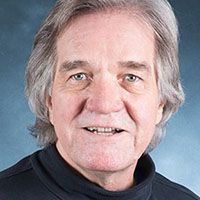

Gifford specialized in landscape, first painting scenes of the Hudson River, the Adirondacks, and the mountains of Vermont. He traveled to Europe in 1855–57, when he met and traveled with Albert Bierstadt. Gifford served in the New York Militia during the Civil War from 1861–63 (see photo).

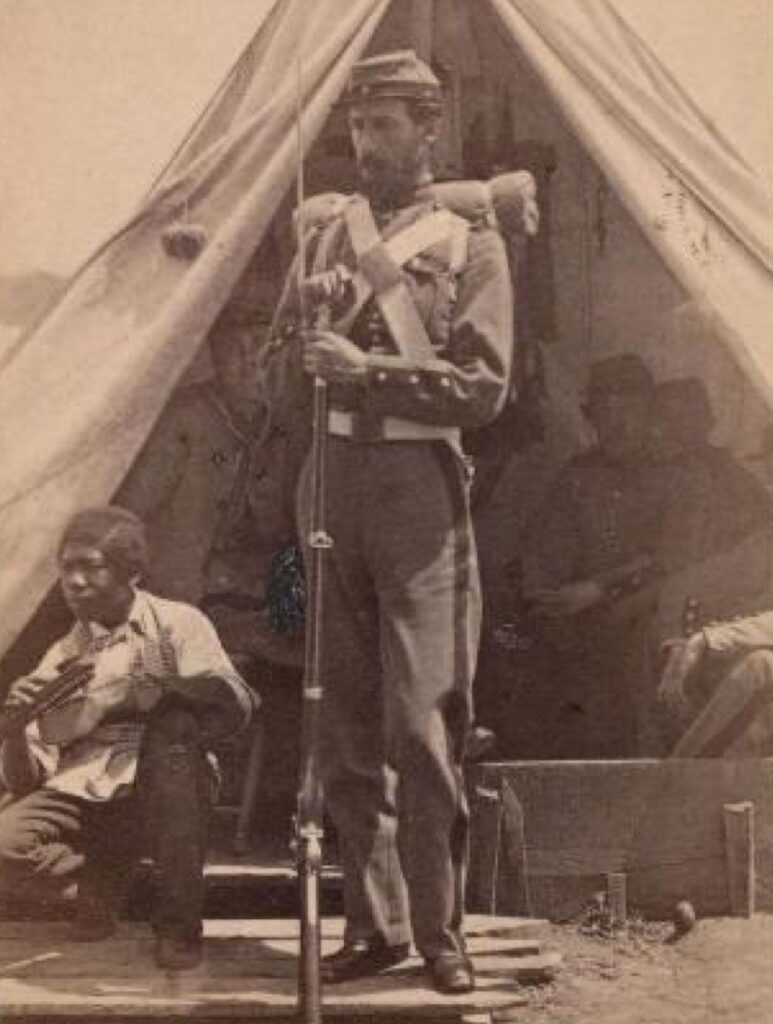

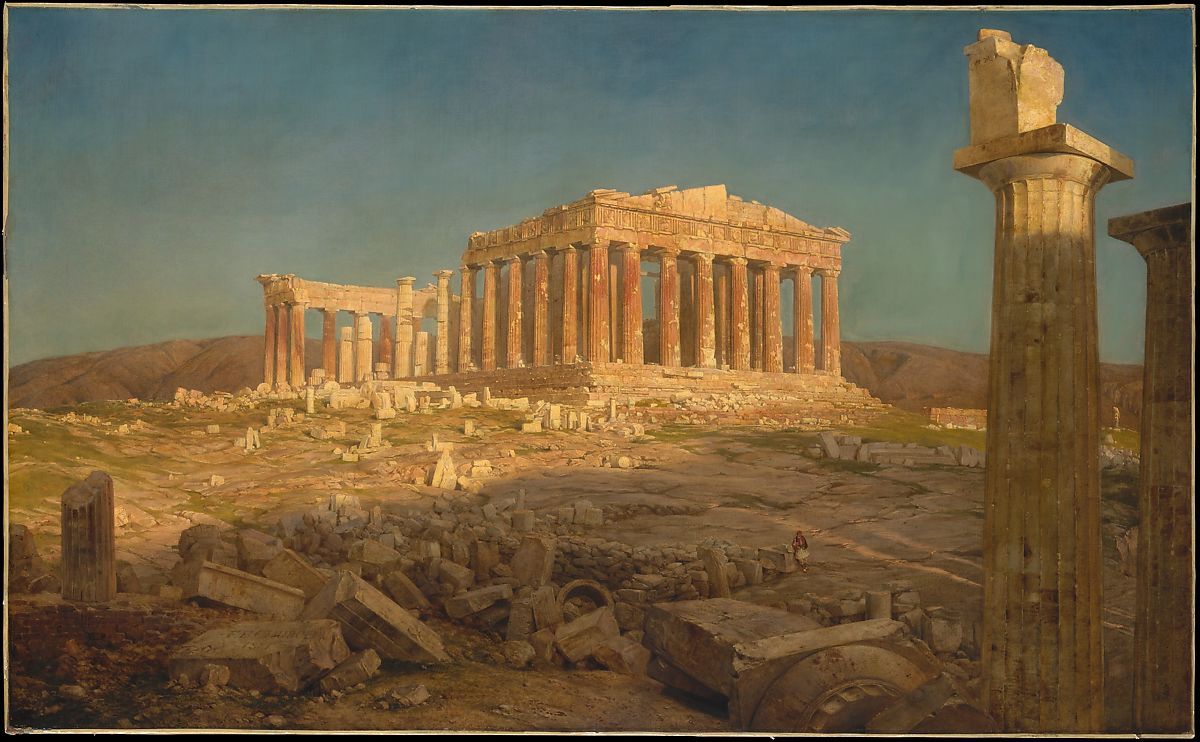

In 1868–69, Gifford made his second and last European visit, this time adding an excursion down the Nile and stops in Turkey and Greece. From sketches made at this time, he later created several important versions of The Ruins of the Parthenon, including a larger canvas in the National Gallery of Art (see image). His paintings are precise and filled with light, linking him to the luminists. The accurate detail of this painting suggests that he used photographic imagery as well as his sketches. The ruins of this still noble temple evoke comparisons of past and present. The ancient Greek civilization was widely seen as the birthplace of democracy; the enduring ruins were particularly poignant in the aftermath of the Civil War. It was one of his last works; Gifford died of malaria in 1880.

Marina Berzins McCoy

Professor, Philosophy

In the field of philosophy, “perspectivism” emphasizes the perspectival nature of all knowing. We perceive the world from particular points of view, and do not simply experience the world in its completeness. If I see one side of a mountain, its other side is obscured. Likewise, a mountain at a distance is experienced radically differently than one that I am hiking. The categories that we use in order to interpret the world are also perspectival. To define beauty as the harmonious captures one aspect of beauty, but not what Plato named as “Beauty itself.”

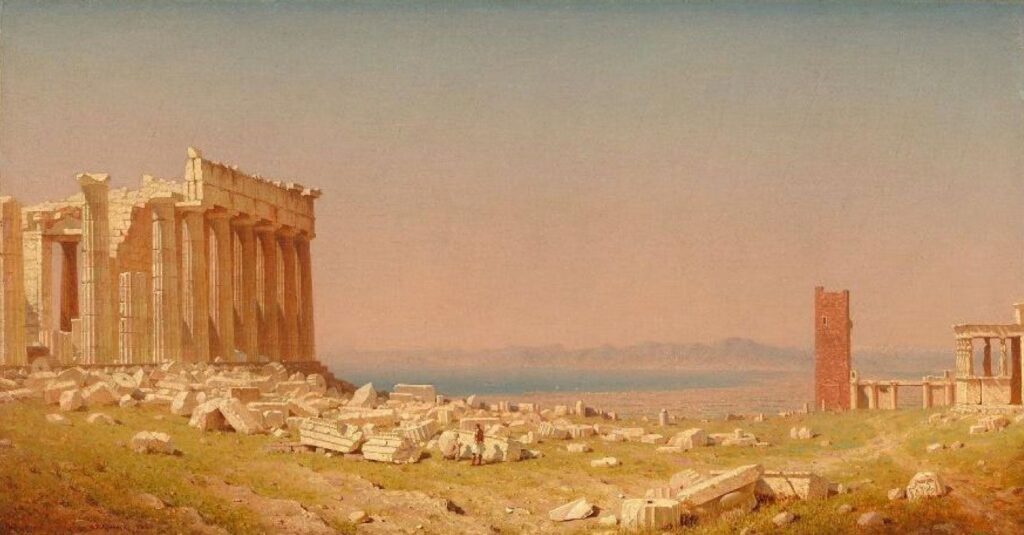

Sanford Robinson Gifford’s The Ruins of the Parthenon is deeply engaged with perspective. Many see this 1880 painting as a response to an 1871 one by Gifford’s friend, Frederic Edwin Church (see image). Both treat the subject of the Parthenon. Church takes a perspective from below the building, looking up at its decaying majesty central to the space of the painting. It is illuminated by sun and warm colors. Church’s ruins hark back to a nostalgia for the Athenian Empire under Pericles. Gifford, in contrast, places the Parthenon to the left of his painting, where it forms only one part of the larger landscape. In the distance, we see a mountain range, and in the immediate foreground, the tiny figure of a person near fallen stonework. The partially deteriorating Parthenon exists somewhere between the brevity of human life and the enduring mountains. Gifford’s work resituates our vision so that we can more clearly see human accomplishments as “in between.” In regarding this work in dialogue with Church’s, we are also invited to grow in our self-understanding as perspective takers and makers.

Nancy Netzer

Inaugural Robert L. and Judith T. Winston Director, McMullen Museum and Professor, Art History

Gifford made several paintings, of which this is one, based on a sketch created during his visit to the Acropolis in Athens in May 1869 (see image). The artist professed they were “not…picture[s] of a building but…picture[s] of a day.”1 Regardless of his intent, the east portion of the Parthenon appears here as a relatively accurate representation of the Greek temple after it was stripped of about half of its original fifth century BCE sculpted frieze, metopes, and pediments by the Earl of Elgin and his agents between 1801 and 1812. Shipped shortly thereafter by Elgin to London, those sculptures by 1832 had become highlights of the British Museum’s collection (see image). Elgin claimed to have removed the marbles with the permission of the Ottoman Sultanate which exercised authority over Athens at the time and to which he was then British ambassador. Discussions between British and Greek officials continue to this day about whether the Parthenon Marbles were looted and should be returned to Athens, because of their cultural importance to Greece, where they could be appreciated by the public in proximity to the other Parthenon sculptures in the Acropolis Museum opened in 2009.

1. His monumental, and presumed to be his final, painting of the scene now in the National Gallery in Washington, bears the date 1880. The present work could have been completed any time after the 1869 sketch, to which it is very close in detail, and Gifford’s death in 1880.