William Bradford (1823-92)

Among the Ice Floes, 1878

Oil on canvas, McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch Collection, 2022.46

Jeffery Howe

Professor Emeritus, Art History

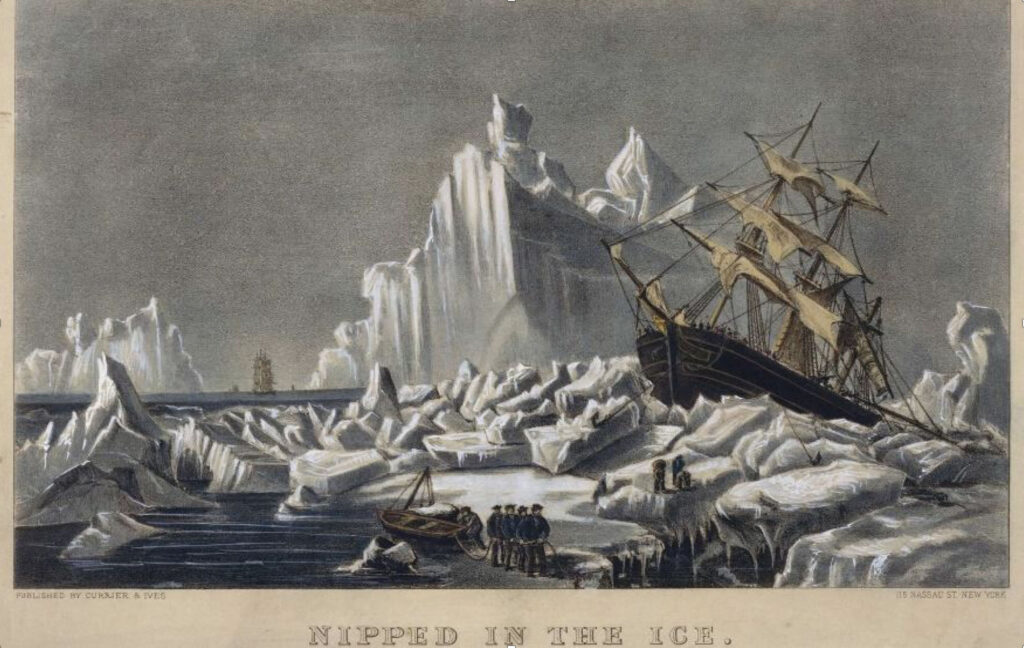

William Bradford was a largely self-taught painter, drawn to scenes he described as “wild, strange and magnificent.” He instigated several expeditions to the Arctic, supplementing his sketches with photographs of the natural beauty and dangers of the polar regions. Reflecting popular interest in the heroic and frequently tragic voyages of explorers and whalers, he published a book titled The Arctic Regions, Illustrated with Photographs Taken on an Art Expedition to Greenland (1873). Bradford also provided images of these exotic and forbidding seascapes for mass produced lithographs by Currier & Ives (1835–1907). In this painting, small figures of sailors toil on the ice, while their three-masted ship sits with sails furled. Large icebergs balance the composition, and a distant vessel is shrouded in mist. It is an image of perilous work, adventure, and the sublimity of the polar regions.

Oliver Wunsch

Assistant Professor, Art History

Caught in the ice floes, a group of men face a perilous moment in the Arctic. The painter, William Bradford, had confronted a comparable situation himself. In 1869, he traveled up the west coast of Greenland, turning back only when ice threatened to trap his ship in the uppermost reaches of Baffin Bay. This painting captures the overwhelming desolation that Bradford encountered there, where he saw what he described as an infinite expanse of ice that lay “perfectly unbroken, except where great icebergs pierced through it.”1 To capture the vastness of the landscape, Bradford here juxtaposes the triple masted ship in the foreground with a similar vessel in the distance, which appears miniature in comparison with the iceberg at the composition’s center. Ant-sized men shuttle across the ice between the ships, scarcely visible through the haze.

Although Bradford based the painting on his experience, he did not seek to create a faithful record of his voyage. He generally composed his Arctic paintings by combining sketches from his trip, scenes recorded by the two photographers who accompanied him, and elements of his own invention. The ship in the foreground of this painting resembles the vessel from Bradford’s expedition, the Panther, but with a notable modification: Bradford here eliminates the smokestack for the Panther’s coal-fired steam engine, indicating that the men in the painting must rely on sail alone to extricate themselves from their predicament. Photographs of the Panther (see photo), by contrast, show a dark plume of smoke billowing from its chimney as it burns through the five hundred tons of coal that it carried as fuel.2 That carbon-loaded exhaust would, unbeknownst to Bradford, come to threaten the existence of the Arctic landscape that had struck him as boundless and eternal.

1. Quoted in Richard C. Kugler, William Bradford: Sailing Ships & Arctic Seas (New Bedford: New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2003), 79.

2. For the fuel capacity of the ship, see John Wilmerding, William Bradford, 1823–1892 (New Bedford: Whaling Museum of New Bedford, 1970), 16.

Ethan Baxter

Professor, Earth & Environmental Sciences

Viewed in the context of climate change, Bradford’s paintings depicting the frozen polar regions from one hundred fifty years ago conjure up feelings of anxiety and reminiscence in a geoscientist. Anxiety, because such Arctic scenes have already become far less pervasive than they were in Bradford’s time and point to a troubling climate future that is upon us. Reminiscence, because those icy scenes may someday be gone forever, preserved now only in memories, illustrations, and paintings like this and his Trapped in Packed Ice nearby. Every September, Arctic sea ice melts and reaches its annual minimum extent. Warming climates have reduced the areal coverage and thickness of Arctic sea ice by about 60 percent since 1878 when Bradford painted this work (see figures 1a, 1b), and all of that reduction has occurred since c. 1970. At its present rate of decline, summer Arctic sea ice will be completely gone sometime in the latter half of this century. While the opening of shipping lanes in the Arctic might seem attractive to mariners like the souls pictured in Bradford’s works (like the fabled Northwest Passage that opened for the first time in 2012, see figure 1c), the accompanying consequences of global warming will far outweigh this apparent benefit. Ice, a majestic blue-tinted rock in its own right, is slowly fading from the surface of planet Earth for the first time in human history. Bradford’s painting captures its story.

Christy Pottroff

Professor, English

Arctic expeditions—like those depicted in this painting and Trapped in Packed Ice by William Bradford—were exercises in extremity. Driven toward the impossibly remote landscapes of the Arctic Circle, sailors endured extreme temperatures and traversed a harsh and unfamiliar ecosystem where the sun shines constantly in the summer and darkness falls for months every winter.

Hundreds of ships sought the perils of the ice over the course of the nineteenth century—to scout out and forge faster trade routes through the Arctic Circle. Most ships carried about fifty men, traveled in small fleets, and were provisioned for voyages of two to three years. Many were funded by European national governments, who imagined themselves to be building the infrastructure for global trade—through the icy ends of the Earth.

Within this world of extremes sits American painter William Bradford, cold—shivering, despite his layers of winter wear—sketching, drafting, and painting in subzero temperatures. This work captures the domineering, ice-chiseled landscape of the Arctic, where icebergs tower over ships, rendering sailors miniscule by comparison. Bradford’s brush also elaborates the eerie and uncanny light of the North for his viewers: Among the Ice Floes is haunted by haze and shadow. Light was scarce in the Arctic; Bradford’s brush finds it, pulls it from the frozen context, and works against the elements to preserve its effect in scenes on canvas.

In some respects, the Arctic expeditions of the nineteenth century were failures—the ice-bound passage was not a viable trade route, thousands of human lives were lost seeking it out, and the expeditionary and capitalistic values that charted the paths of these ships continue to be driving forces of climate change. These paintings by Bradford are some of the greatest successes of the expeditions (along with the travel narratives, ship-made newspapers, and other testaments to human fortitude under extreme environmental conditions). Bradford’s paintings attest to the formidable and otherworldly nature of the Arctic as it was in the nineteenth century—and inspire respect for a landscape that faces the greatest threat to climate change today.

For a nonfiction study of a broad range of polar media, read Hester Blum’s The News at the End of the Earth. For Antarctic fiction, pair Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and its haunting and unfinished ending, protagonist adrift near the South Pole—with Mat Johnson’s satirical fantasy Pym, a modern retelling that traverses the same geographical extremes to explore enduring questions of race and racism in the American imagination.