Forbidden Art: The Postwar Russian Avant-Garde

October 15–December 10, 2000

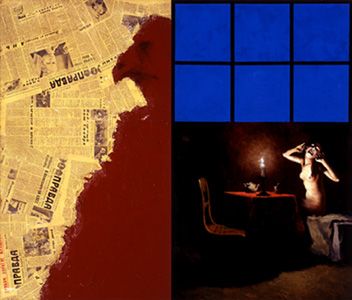

Forbidden Art: The Postwar Russian Avant-Garde presents 77 works by Soviet underground artists who dared to challenge the Communist government’s monopoly on artistic expression. After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, many Russian artists believed that the new Communist state would give them unprecedented artistic freedom. Instead of filling commissions for the wealthy elite, they would now create authentic art for the people. Avant-garde artists such as Vasilii Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Luibov Popova, El Lissitzky, and Vladimir Tatlin believed that Modernist forms would be the true artistic language of the liberated, egalitarian Soviet society. These idealistic artists were bitterly disappointed when, in the early 1930s, the Communist government set strict guidelines for Soviet art.

The official style, known as Socialist Realism, emphasized narrative, didactic subjects and classical composition. The Ministry of Culture of the USSR proclaimed that “the truth and historical concreteness of the artistic depiction of reality must be combined with the task of the ideological transformation and education of the workers in the spirit of Socialism.” Furthermore, artists were “to create works with a high level of craftsmanship and a high level of ideological and artistic content.” The entertainment of “irrelevant” or subjective styles, such as abstract art or Surrealism, was strongly discouraged.

The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 brought hopes of artistic freedom. With Nikita Khrushchev’s revelatory Secret Speech in 1956 and the first official statements on the horrors of the preceding era, the truth of the dictator’s crimes began to emerge. New civil and cultural liberties seemed imminent. Bold artists joined literary and scientific figures like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrey Sakharov on a dangerous path of alternative expression, issuing provocative statements and formulating new aesthetic theories. The inevitable result was a series of confrontations with the government, epitomized by the so-called Bulldozer Exhibition in 1974, when police drove bulldozers through the exhibition, scattering the painters, and then doused the paintings with fire hoses.

The state suppression of alternative ideals continued after Khrushchev, through the Leonid Brezhnev years and the brief tenures of Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko. Nevertheless, the Soviet underground continued to expand, pressing for creative freedom and public recognition. In many ways, the 1970s marked the zenith of the nonconformist movement’s originality and polemical power. Finally, in the late 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (rebuilding) marked a new era of free and energetic cultural expression. The auction of Russian Avant-Garde and Soviet Contemporary Art held at Sotheby’s in Moscow in July 1988 formally introduced nonconformist art into the international market. The emigration of Russian nonconformists to Europe and the United States also gave Western audiences new access to Russian alternative art.

Forbidden Art: The Postwar Russian Avant-Garde begins with a Socialist Realist work, Nikolai Kritski and Group’s Power to the People. The six sections of the exhibition trace the different ways that Soviet artists reacted against Socialist Realism, beginning with the first waves of nonconformist artists, the Reform School and the Radical School. The next two sections present Sots Art and Moscow Conceptualism, two forms of artistic innovation that emerged in the 1970s. The final section gathers together works by artists from St. Petersburg.

Forbidden Art: The Postwar Russian Avant-Garde is drawn from the Yuri Traisman collection. The exhibition is organized and circulated by Curatorial Assistance, Inc.